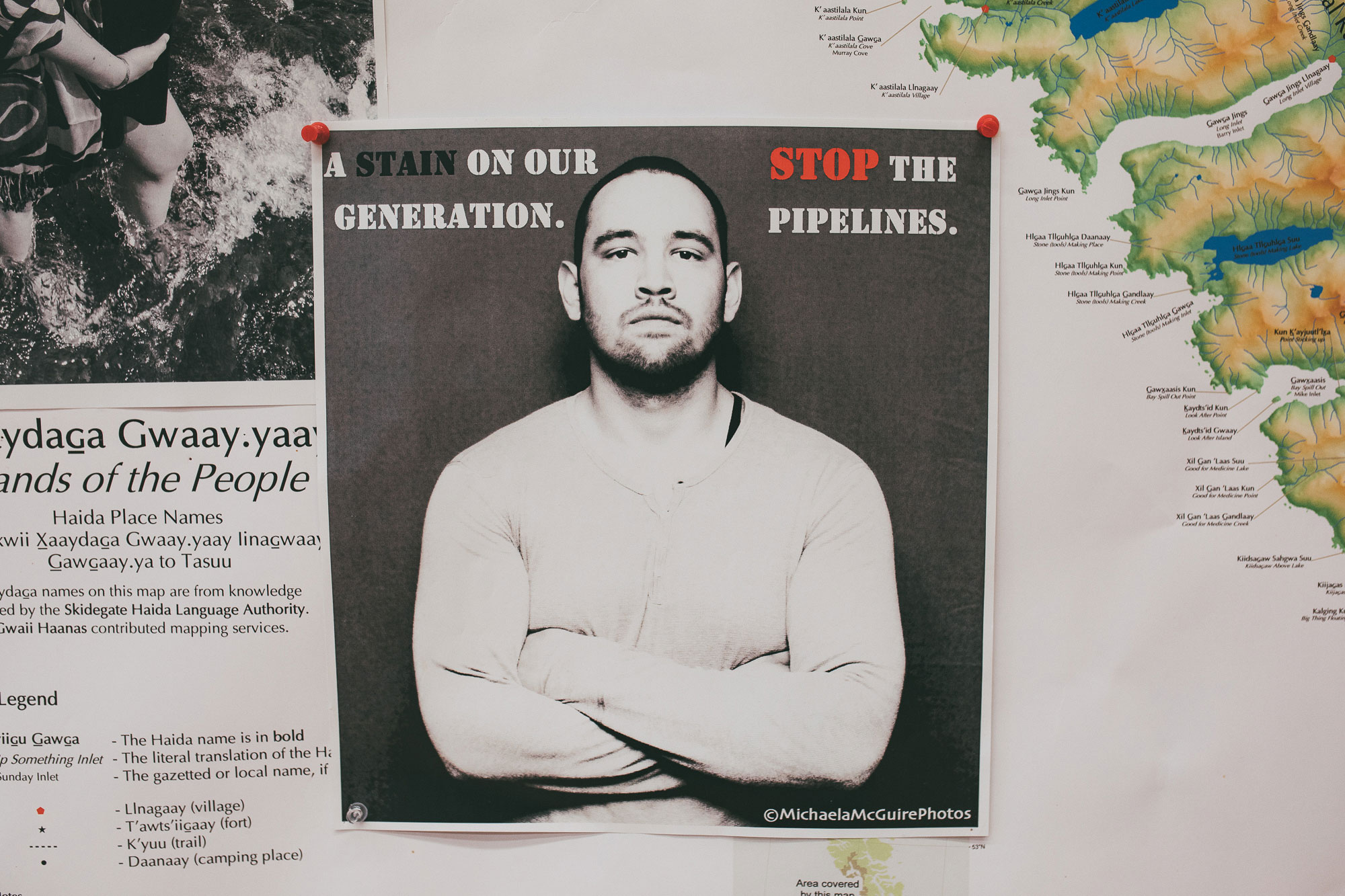

The poster was nestled among old photographs, Haida language booklets and maps of the Islands. A young man with his arms crossed, in black and white: “A stain on our generation. Stop the pipelines.” Gradually I noticed the anti-LNG t-shirt and the other pipeline resistance posters. They were there, but not set apart.

They were surrounded by Haida culture—at the heart of the Islands.

I didn’t have any specific conversations about oil, pipelines or supertankers while I was on Haida Gwaii, but I did pick up a copy of Haida Laas that spoke about the issue, and it was present on the Islands in a way that is hard to describe. It was on the counter at Queen B’s coffeeshop in Queen Charlotte. It was on the beach west of Skaayas, and on the wall of the Skidegate Haida Immersion Program longhouse.

A name that I heard multiple times was Valine Crist, and when I looked her up I found that she had written a master’s thesis about Haida Gwaii’s response to the proposed Enbridge Northern Gateway project. That’s where I’m pulling most of the research for this article.

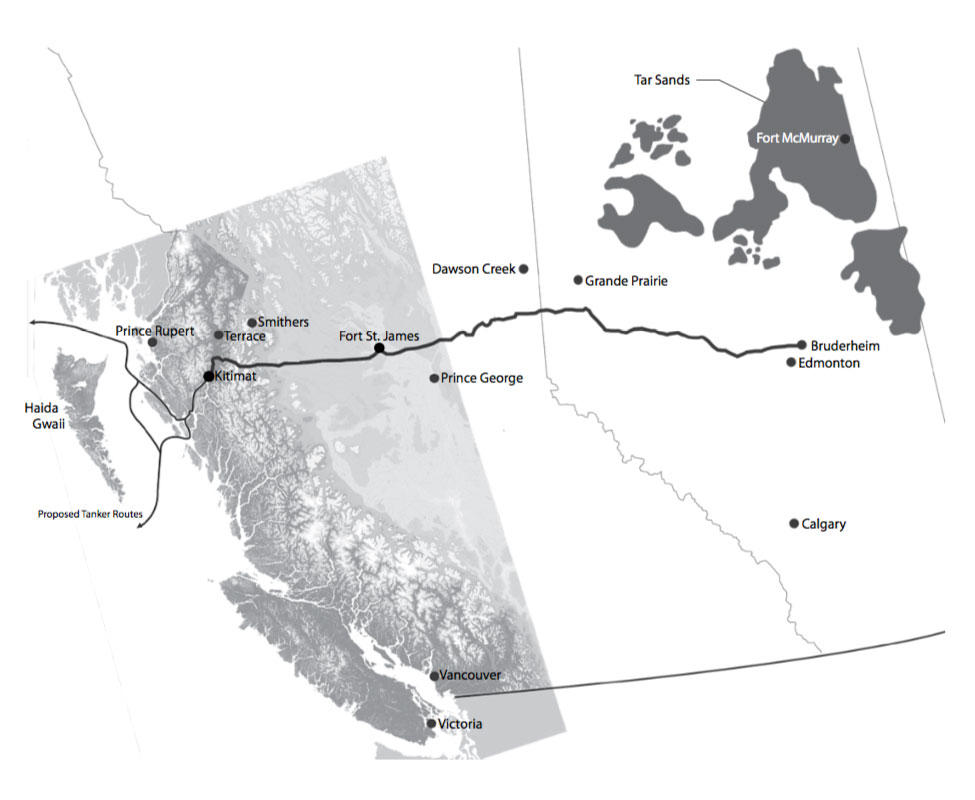

Northern Gateway was a proposal to build two pipelines from central Alberta to Kitimat, ultimately transporting half a million barrels of unrefined bitumen, every day, to the northern British Columbia coast. Throughout the proposal process, Enbridge was confronted with their track record of over 800 oil spills between 1999-2010 with 20 million litres of contamination; and diverse opposition concentrated on specific details of the project. Northern Gateway would require, for example, 225 supertankers to navigate the Douglas Channel and cross the Hecate Strait—the fourth most dangerous body of water in the world. A catastrophic oil spill was, according to the opposition, inevitable.

Northern Gateway was approved by the Harper government in 2014 but Enbridge couldn’t finalize a shipping contract to begin construction before a coalition of Indigenous nations overturned the federal approval in June 2016. In November 2016, Northern Gateway was formally rejected. At the end of March 2017, the communities of Haida Gwaii held a day-long celebration with hundreds of people in attendance.

There’s more to say about federal politics, oil industry and consultation processes in Canada, but what I want to focus on is the Indigenous leadership to this resistance, beginning with the voice of Valine Crist.

“Indigenous-state relationships require an overhaul,” she wrote, “particularly in regards to exploitative resource development projects that infringe on Indigenous homelands. Traditional Indigenous laws and ideologies that govern local stewardship are often in contrast to dominant paradigms, and all too often, Indigenous values are suppressed by mainstream practices.”

According to Crist, Northern Gateway provided a catalyst for local communities to coalesce and challenge economically motivated agendas threatening Indigenous sovereignty. “Central to these coalitions,” she added, “are Indigenous peoples who are aligning with non-Indigenous neighbours to renegotiate power relationships.”

That’s what happened on Haida Gwaii. During the National Energy Board’s Joint Review Panel process in 2012, dozens (or hundreds) of Indigenous and non-Indigenous community members—Elders, elected leaders, local fishermen, traditional knowledge holders—presented oral testimonies describing what was at risk in the face of Northern Gateway.

“Our culture is about our relationship to this place, our home, and that’s what we are mandated. That’s our responsibility as a living generation of an ancient nation, to protect that, and protect that we will…We declared Duu Guusd Tribal Park…We drew a line in Gwaii Haanas and said, ‘That area is intact, you’re not going there.’ We never asked anybody permission. We had our Elders’ direction and…so we made plans. And then we said to the governments, to anybody who would listen, ‘This is Haida land, these are the rules. We’ll work with you. We’ll negotiate with you. We’ll talk with you. We’ll share. We’ll get along, but this is the Haida vision.’” Miles Richardson

“There is a reason why the logging industry collapsed and drove my community into a decade-long depression that it is still in. It wasn’t due to park creation or land use planning, and it wasn’t due to blockades. It collapsed because it wasn’t sustainable.” Evan Putterill

In Crist’s conclusion, she wrote: “Even with Haida Gwaii’s history and experiences fighting to protect the Islands and its people from outside threats, I have heard endless locals—Haida and non-Haida, young and old—stating that the Northern Gateway will be the battle of our lifetime. […] We are finding new ways to form relationships and align with our neighbours—neighbours who are becoming unexpected allies because of fundamental shared values and lifeways. In so doing, we are fostering intensely powerful relationships that deconstruct inequalities and injustices.”

That’s a powerful statement. Particularly because there are Indigenous communities all across Canada and the United States rising up to protect their lands and our collective future. Our allyship with them matters.

I already wrote about this in an article about Oka, but it’s a message that bears repeating. These fights are happening now, and they are not all being won. Two weeks ago, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of developers building a ski resort in the sacred Qat’muk valley. Last week, Kinder Morgan appealed to the National Energy Board to undermine the city of Burnaby’s local government. COP 23 concluded this past weekend, with a conclusion that the planet is on track for a catastrophic 3 ºC of global warming.

If there’s anything I’ve learned from the people of Haida Gwaii, or the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs, or the Elders of Northern Gespe’gewa’gi, it’s that news articles like these are about real people, and real communities—and a real history of violence and colonization that we have yet to adequately confront.

Map from the Journal of the Council of the Haida Nation. Poster image from Haida Gwaii Trader.