I wrote about Oka at the end of June. The first thing I read about was the leadership of Ellen Gabriel as one of the spokespeople for the Mohawk resistance. The first thing I wrote was that the land issue is still unresolved. Two weeks later, I came across a video of Ellen Gabriel defending The Pines of Kanesatake against development.

Not from 1990. From 2017.

So I’ve been meaning to return to the subject of Oka for the last few weeks. Of course Kanesatake isn’t the only ongoing land dispute, but having written about it as a history, I felt the need to write about it as a present issue.

In 1995, Gabriel said that nothing had been resolved and that they would have to continue to struggle for the land. In 2017, she was just as clear. “What we’re telling you, mister mayor, in front of all these people, is that you cannot build any more on this land. We’re not going to allow any more development here, on our traditional territory.”

In another video posted on APTN National News, the mayor asked her pointedly how many trees had been cut down to build cigarette shacks. “You have no clue what you’re talking about,” she responded. “Colonial poverty is what has caused us to put those things up.”

“He never had a right to buy this land. Nobody every had a right to sell this land. Nobody. The only people who have a right to this land are the Mohawk people who have been here for centuries, long before your relatives came. This is disputed land.”

This is exactly what happened in April 1989.

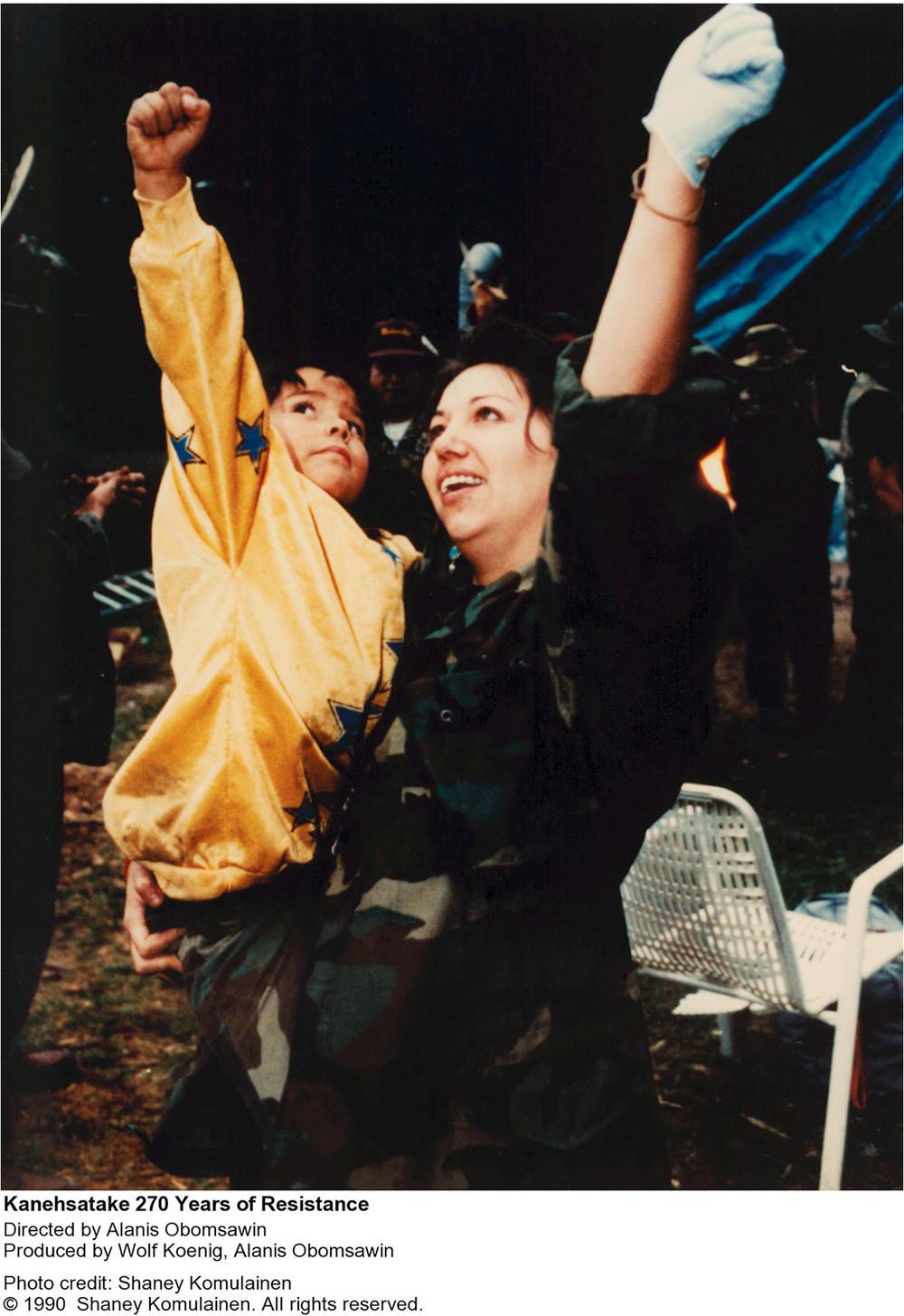

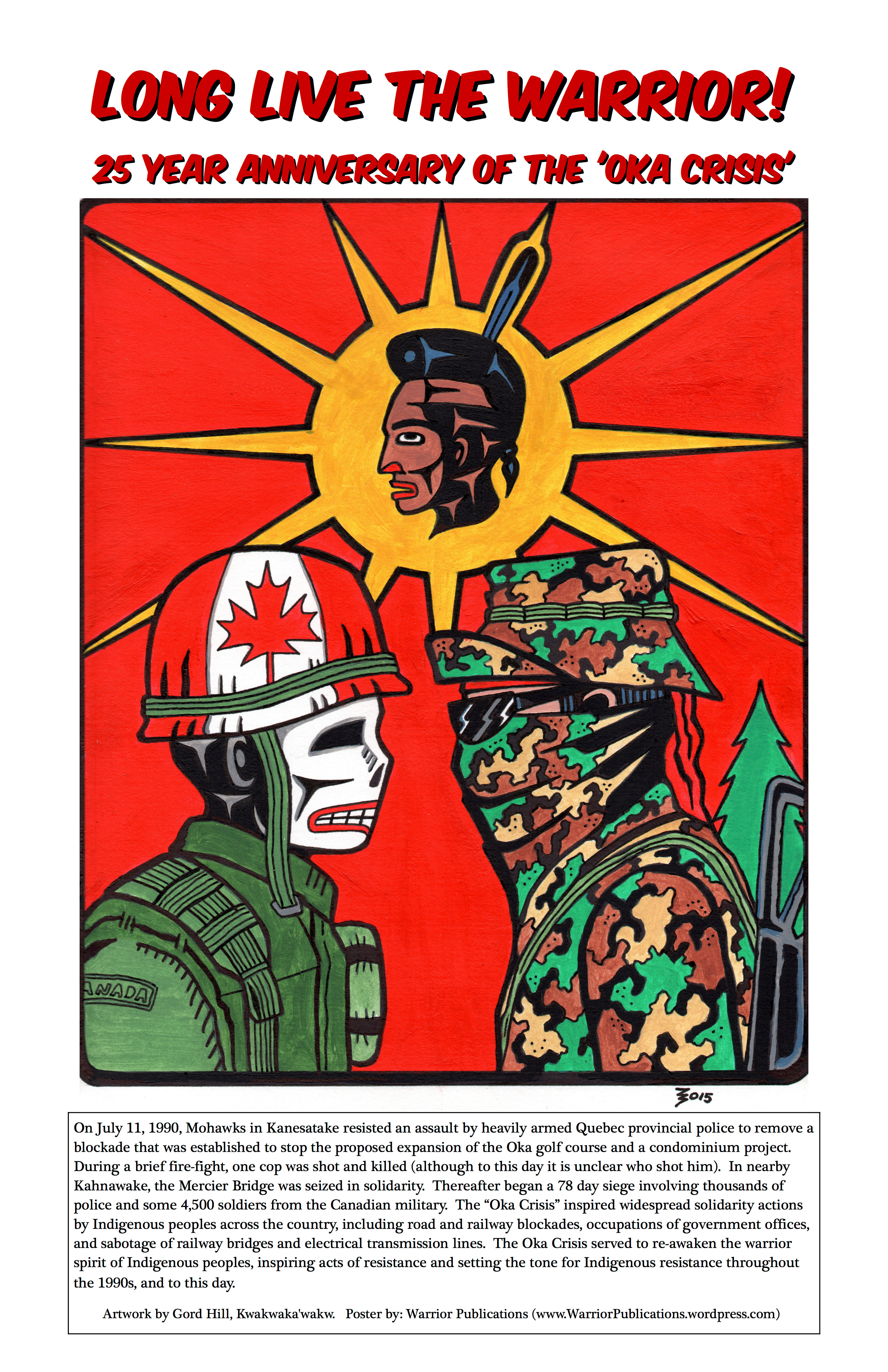

These photos are from Oka in 1990, but I could just as easily be sharing images of Standing Rock in 2016, where the Sioux blockaded the Dakota Access pipeline; or Clyde River in 2017, where Inuit hunters were prepearing to swim in the frigid Arctic Ocean to block seismic testing before they won a Supreme Court ruling.

Barriere Lake. Klabona. Muskrat Falls. Grassy Narrows. Unist’ot’en. The Yinka Dene Alliance. The Treaty Alliance Against Tar Sands Expansion. All in 2017. All in Canada.

The connection of Indigenous-led resistance to Oka is visible even today. Grand Chief Serge Simon of the Mohawk Council of Kanesatake has spoken out against the current escalation of tension within Oka, but has also promised civil unrest against any pipeline expansion that jeopardizes Indigenous lands and rights.

“We salute all the water protectors, coast protectors and climate warriors on the front lines of these pipeline battles, standing up for Indigenous rights, the water and a safe climate. Resistance to Kinder Morgan's Trans Mountain Expansion tar sands pipeline and tanker project will be strongest in British Columbia, but it won't stop there: Kinder Morgan can count on fierce resistance all over North America by Indigenous people and their allies.” Grand Chief Serge Simon

At the end of July, I posted an interview with Jim and Donna Sinclair about their resistance to Energy East. During that interview, I also found out that they were at Oka in 1990 as journalists. This is where the pieces of history, for me, started to connect. The attempted development on Kanesatake territory is not separate from the collapse of the Atlantic fishery territory. The intervention of the Sureté du Québec in Oka is not separate from the violence of the NWMP in Winnipeg. Mohawk resistance in 1990 is not separate from opposition to pipeline expansion in 2017.

I don’t mean Canadian history is a conspiracy. I mean our history is connected in ways for which we often don’t give it credit. We tend to think about these ‘crises’ as disconnected events, rather than pieces of a larger history with oppression and exploitation as tools of nation building.

Within that history, we can see different worldviews emerge.

“They represented a culture very different from the dominant culture in Canada,” said Donna about the Oka warriors, “standing up, displaying a lot of wisdom. […] We saw something in action that was quite different from the way we function. We saw a form of resistance that was very effective. Very powerful resistance. Very principled. It was thought-out, it was ritualistic, strong, clear.”

When Donna wrote about the confrontation back in 1990, she quoted Dale Diome from Kahnawake Mohawk Territory: “Warrior is a European term that is used for our men who protect the territory. We have our own name for them, Rotiskehrahkete. That means he-who-carries-the-peace. One of their duties is the protection of land. If the land is protected, then there is peace.”

Donna spoke about different standoffs in the 1990s—Oka, Gustafsen Lake, the Meech Lake Accord—and how they influenced politics in the decades following. “There was a lot of moments where First Nations were standing up to be counted, and saying, ‘We’re not going to back down.’ That has fed into what’s going on now.”

“A large part of what’s going on now with the anti-pipeline stuff is the understanding of non-Native people that they’re learning from Native people that the land is a spiritual matter. I think Oka was part of that dawning. It was one of those moments where we saw another way. They held that up for us.”

Donna and Jim also talked about the involvement of the United Church of Canada in supporting the resistance at Oka. “We witnessed a lot of First Nations people in our church standing up and saying, ‘You need to stand with us. You apologized to us. You stand with us now.’ And we did. I’m really proud of that. The United Church did stand with them.”

“There was always a pastoral presence from the United Church right in behind the lines. They were very aware that there is a Québec law that says you cannot interrupt a worship service in progress. So there was a continuous worship service for seventy-two days in the school where the [Mohawk] people would come for respite.”

Lastly, they spoke about the lessons to be learned by paying attention to struggles for justice.

“There’s people all over the place who behave with such courage. And that’s our job now, I think. All of us. This is the age of Trump. Resistance is absolutely crucial. What else can you do?”

“These are the stories that are far more important,” they told me as I prepared to leave. “They are stories of a peculiar importance that’s not always conveyed. They’re far more important now. We have to know those stories, because we have to write the alternate history now.”

My purpose of returning to Oka was to draw attention to the ongoing history of land appropriation in Kanesatake, and to the connections between these different events that I’ve studied within broader Canadian history. My hope is that with one foot on the past, we can step into our present political tensions and injustices with strength and resolve.

“We can start by talking to each other about Indigenous issues, educating and learning, while refusing to repeat the mistakes the led to July 11, 1990. We can’t change the past but we can all shape the future, which starts with giving the respect and honour our people deserve.” Steve Bonspiel, The Oka Crisis was supposed to be a wake-up call

Photos by John Kenney and Shaney Komulainen. Artwork by Gord Hill.