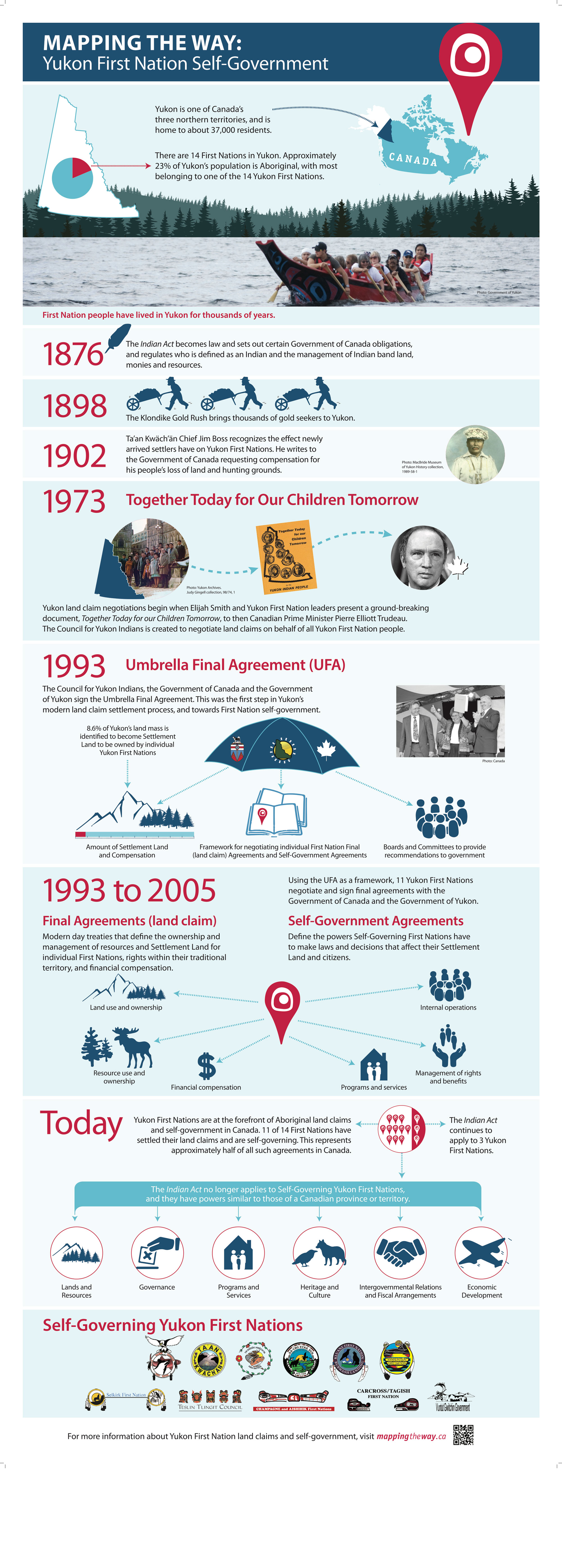

I didn’t know self-government existed in First Nations in Canada outside of Nunavut. I knew that the Indian Act first passed in 1876 was still in effect. I knew self-determination and sovereignty was part of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Truth and Reconciliation Final Report. But I didn’t know that eleven of the fourteen First Nations in the Yukon were already self-governing and had settled land claims with the Canadian government.

Here’s some of what I’ve learned.

Starting in the mid-18th century, the Yukon First Nations experienced European contact indirectly through trade between the Russians and Tlingit. When the Yukon First Nations began trading with their coastal neighbours for Russian goods, their lifestyle began to change as a result of European commerce. In the late 19th century, a small number of White fur traders from eastern North America began to arrive in the southern Yukon. They brought with them a gradual increase in prospectors, until the discovery of gold in the Klondike in 1896 resulted in an estimated 60,000 White people to the Yukon by the turn of the century. The traditional cultures of the Yukon First Nations, already shaken by an unprecedented loss of population due to disease and the emergence of residential schooling, continued to be affected.

In 1941, the American army moved in to the build the Alaska Highway. The Dawson Highway was built in the early 1950s, linking Dawson to Alaska and Whitehorse. The infrastructure further undermined Indigenous ways of life and allowed for the continuation of colonization into the heart of the Yukon. “The money left with the Americans,” reads the 1973 document establishing the Yukon First Nations settlements. “The traps were rusted and the cabins in need of repair. Many did not go back to the traplines. Some of us moved into shacks on the edge of the White communities, and there were no jobs. Then came Indian Affairs. They made up the Band lists. Then came welfare. Then they invented the Indian Village, where a group of Indians could all be put together. […] So the final program of changing the Indian way of life from one of economic independence to a welfare hand-out was complete.”

In the 1960s, Indigenous cultures were again threatened by the influx of White prospectors, this time focused on mining and oil in the Yukon hinterland and Beaufort Sea. But in 1973, the Council for Yukon Indians presented a document of past grievances and a vision for a different future to the Prime Minister Trudeau and the Canadian government—the basis of the Yukon land claims.

“We are not here looking for a hand-out. We are here with a plan.” Elijah Smith, 1973

Formal resistance to colonization in the Yukon began with Chief Jim Boss of the Ta’an Kwäch’än during the Klondike Gold Rush, but it wasn’t until after the announcement of the White Paper in 1969 that the Yukon First Nations began formally organizing for self-government and land claim agreements. This organizing happened under the leadership of Elijah Smith, who helped form the Yukon Native Brotherhood, the Yukon Association of Non-Status Indians and the Council of Yukon Indians. In 1973, he led a delegation to Ottawa to present a document entitled Together Today for Our Children Tomorrow, which became the basis for Yukon First Nation land claims.

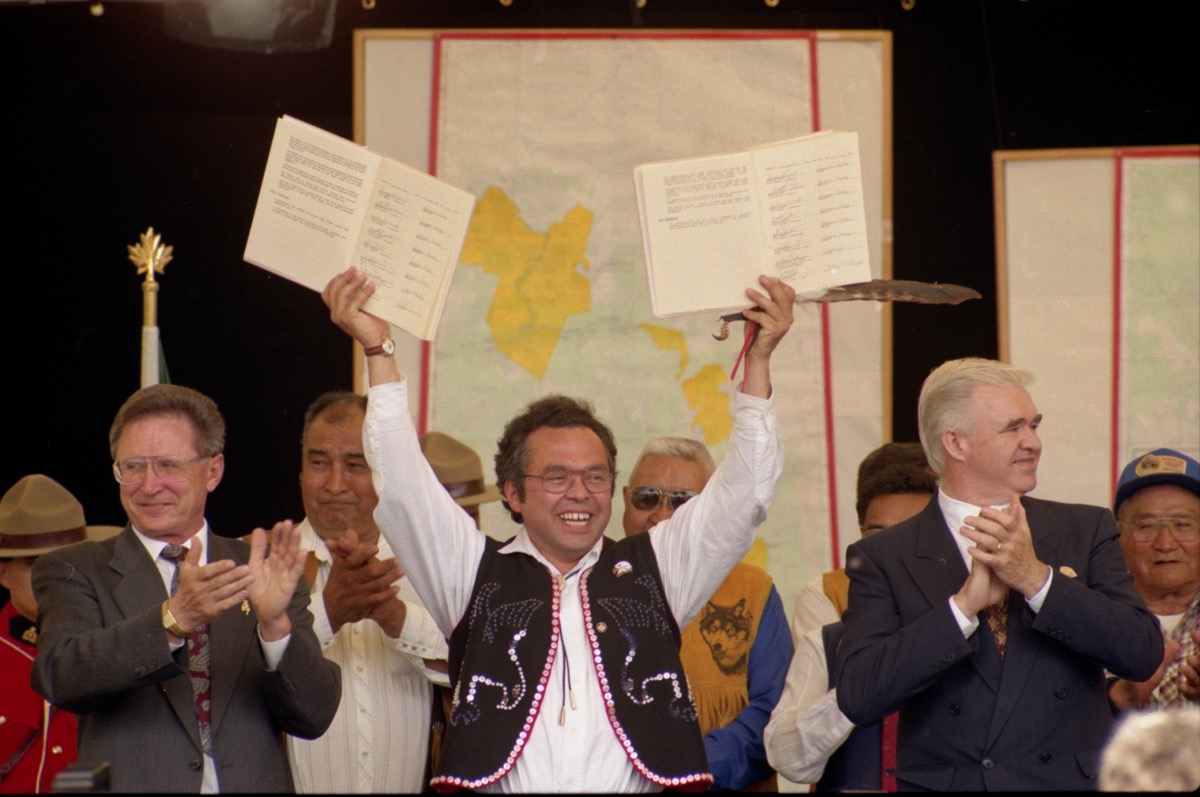

In 1993, the Council of Yukon Indians, the Government of Canada and the Government of Yukon signed the Umbrella Final Agreement, which acted as the political framework for negotiating individual Yukon First Nations self-government agreements. The Council of Yukon Indians included people who were non-status according to the Indian Act but who could prove their connection to Indigenous heritage. Individual land claims and self-government agreements followed from 1993 to 2005. You can read about the different First Nations’ histories and settlements on The Journey to Yukon First Nation Self-Government timeline.

As the Mapping the Way website says, self-government means sustaining the rich cultural legacy of their First Nations. It means control of economic development and the protection and sustainable management of settlement lands. But it’s more than that. I saw it firsthand. Self-government is the high-school student in Dawson who was a member of Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation even though her mother married a White man. Self-government is the Vuntut Gwitchin trapper north of Eagle Plains who was living on the land and teaching traditional trapping as a way of healing. It’s the Singletrack to Success project in Carcross/Tagish First Nation, the Kwanlin Dün Cultural Centre on the Yukon River, the Peacemaker Court of the Teslin Tlingit Council.

“A self-government—it’s almost like ’take back your life.’ And my—this is personal, this is my own personal opinion—take back the way our people once was. We can govern ourselves. We have the ability to manage ourselves. But we were not along the way given a chance because the Indian agents, Indian Affairs, came about throughout our lives.” — Angie Joseph-Rear, residential school Survivor and Chief of Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation during the self-government process

“We have to make sure that when our children—my grandchildren—come in there, you know, they’re being trained to be leaders. They’re going to be going to the university. I know that for a fact. My grandson is only five years old. I know he’s going to go to university. I know my granddaughter is going to go to university. I know they’re going to learn how to take over self-government and run with it. […] A long time ago they were oppressed. Many times they were thrown into mission schools. They were taken away at a very young age—three years old—lived in a mission school, didn’t have the love of their parents. Their parents lost the ability to give them guidance, to take care of them and show them what to do. They got up by the bell, woke by the bell, prayed by the bell, and yet they were told they were sinners and what-not, and everything negative. You bet there’s been a change. It’s better nowadays, you know. Our children are proud of who they are. They’re learning to dance. They’re learning their language. They’re learning to sing.” — Doris McLean, Chief of Carcross/Tagish First Nation in the negotiations leading to the Umbrella Final Agreement

This is far from a complete history of Yukon First Nations self-government. It’s a history that I merely glimpsed while travelling from Teslin to Inuvik, and it’s a history that is still unfolding, both in the Yukon and across Canada. The eleven First Nations in the Yukon represent about half of all comprehensive land claim and self-government agreements in Canada. Some of them would be land claims between the Inuit and the Canadian government between 1975 and 2003. Others I probably don’t know about. As always, there is more to learn.

But the more we learn, the better we move forward together.

Photos from Mapping the Way. You can hear more Yukon First Nation leaders speaking about self-government on the Voices of Vision podcast. You can learn more about the process towards the Yukon land claims in the Council of Yukon First Nations’ four-part video series A Long Journey Home.