I crossed into British Columbia in time for the Dawson Creek Exhibition & Stampede. I expected it to be sort of similar to what I knew from fall fairs in Ontario and the Shigawake Agricultural Fair I learned about on the east coast—but with a rodeo. I wanted to spend time at the rodeo to learn about and document western Canadian culture. These are some of the people and stories I encountered.

It was Sunday morning in Dawson Creek. The fairgrounds were quiet, with a few cowboys drinking coffee as the food vendors set up shop. The sound of early morning rain blended with the warm music of The Amundruds, a country gospel band from Lloydminster, Saskatchewan. I didn’t interview any of them, but it was a start to the day. Cold rain, hot coffee. Music.

As the rain began to disappear above a sky filled with wildfire smoke, I headed west towards the VJV Auction Company auction house. That’s near where I met Brett.

Brett was 13 and had won Reserve Grand Champion for his yearling steer. His hair was wet from the rain and he held a brush for his calf in his hands. I asked if there were lots of kids involved in 4-H like he was. “By age 9, yeah, I guess it’s pretty popular,” he said. “But by the time you’re 15 or 16 you could be buying and selling your own cattle. So you don’t have time anymore.” He said there’s 4-H sheep and goats, but not in the same way. “This is cattle country.”

“I’m a pure-bred cattle owner. I’ve ultimately just gotten into this business because this is what I love.”

He didn’t record a very long audio clip, and he was really more comfortable talking without the audio recording; but I think there’s still something really powerful about a young teenager saying the words ‘this is what I love.’ There was pride in his body language and certainty in his voice.

Brett said it. It was simple as that. With the rodeo queens, however, everything about them embodied love for rodeo culture and western Canada. I photographed them before they left to join the drill team for the grand entry of the rodeo.

The role of rodeo queen started in the early 20th century and according to the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains rose to prominence in the 1930s and ’40s. I sort of accidentally found an article, Queens of the West, that offers a worthwhile glimpse at phenomenon of rodeo queens in the United States.

The royalty at Dawson Creek included Miss Rodeo Canada, Miss Grande Prairie Stompede, Miss North Peace Stampede and Miss Teepee Creek Stampede—and even if I hadn’t looked up more information about rodeo queens, I could have told you that they were the face of the rodeo. They waved at strangers, lifted kids to sit atop their horses and answered a photographer’s endless questions about the sport. They were ambassadors for their respective exhibitions and stampedes, but they also carried a large part of the rodeo culture at Dawson Creek.

Each day the rodeo was preceded by a grand entry led by the rodeo queens, and they remained on horseback throughout the events, corralling livestock and making sure the competition ran smoothly. Having talked and laughed with them in the morning rain, I felt a slightly inexplicable surge of pride to watch them riding assuredly and responsively in front of the crowd that afternoon. And that’s me—an outsider. I can only imagine the pride of the locals.

I didn’t record any audio from the rodeo queens, but I did hang out for a bit with the ‘queen moms,’ who had gotten the horses groomed and tacked up for their daughters.

“Queen moms really are the backstage that makes everything run,” said Sarah, one of the moms. She described providing transportation, taking care of the horses, ensuring that their daughters eat enough. “We make it run at the events.”

“What is it about the existence of the rodeo queen that’s important,” I asked, “like why do you think that’s a culture that’s worth putting all that effort into?”

“That’s an easy one,” she responded. “You don’t need to promote rodeo to people who already do rodeo.”

“The queens are an approachable person that people who don’t know about rodeo can go and ask, and they have all the knowledge. Without having new people brought in, our sport isn’t going to maintain and keep growing. So the queens really promote to people outside of rodeo.”

I gestured to myself. “Yeah, like you,” she said. “Look how much you learned today!”

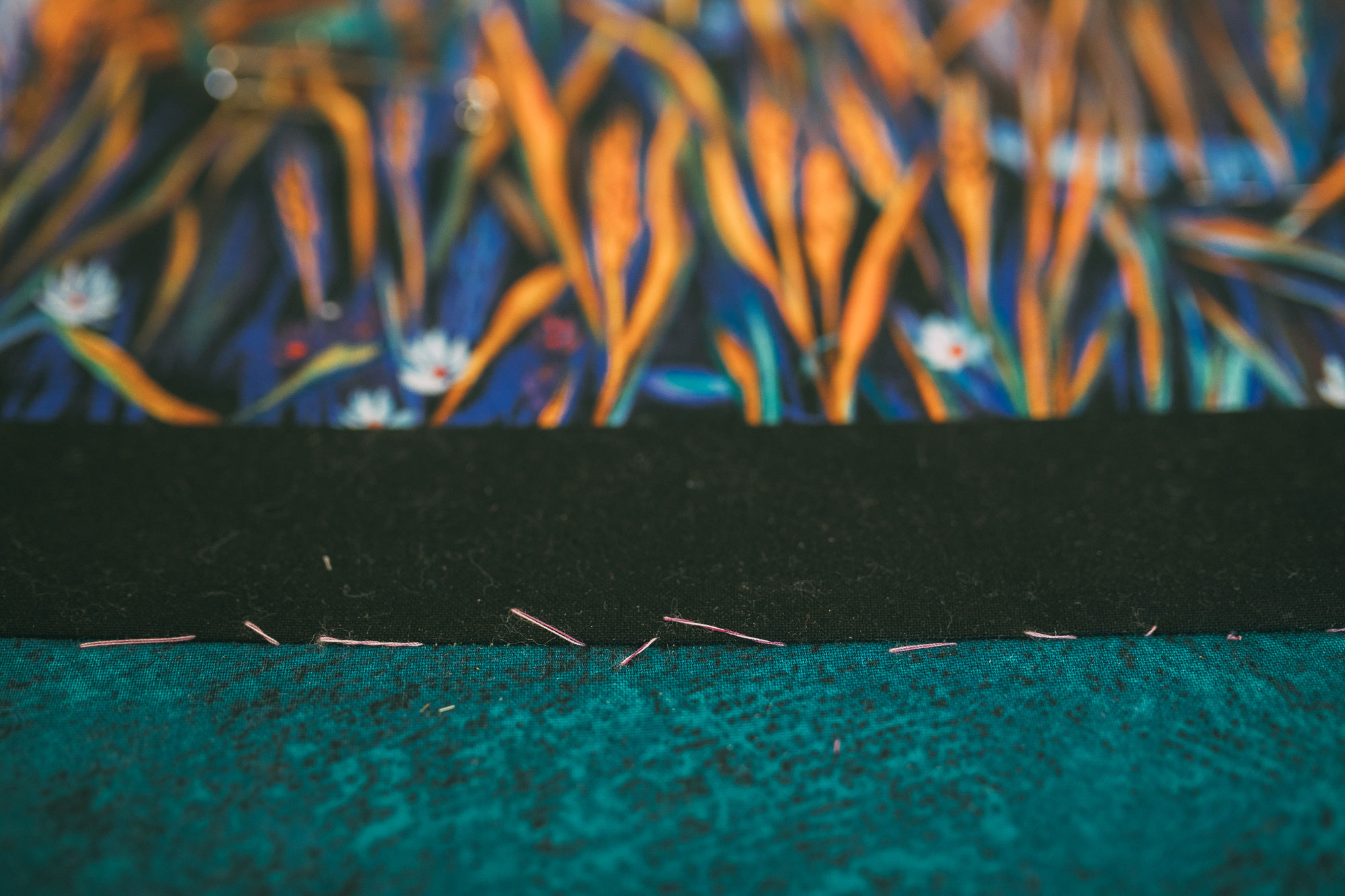

On my way to the rodeo, I stopped in and met two women quilting in the handicraft exhibition. In the same way that the rodeo queens were there to promote and introduce people to the rodeo, Ruth and her quilting partner were volunteering their time to introduce people, particularly kids, to handiwork.

The quilt they were working on had all kinds of stitching, because all kinds of people had contributed to it. I particularly loved the crooked, uneven stitches on the bottom border—clearly a kid’s first try with a needle and thread. They recalled different experiences from the days before—a boy seeing an egg being laid for the first time, the kids bringing their artwork in to be exhibited.

Their space stood perhaps in contrast or perhaps in complement to the agribusiness equipment and livestock industry that surrounded it. At first I thought it didn’t quite belong. Then I remembered Brett’s row of ribbons, and the intricate leatherwork on the rodeo queens’ saddles.

“This is culture. There’s canning, and jams and jellies, the kids’ legos and things, just stuff that they can do and make and create. To me that’s something we need to hang on to.”

From there I ran to the rodeo in time to catch the ending of the grand entry. Cowboys leaned on the bucking chutes and finished tying their chaps. It was time.

I hope the photos speak for themselves, but it’s probably in vain. I want you to hear the whoosh of the honda knot as it leaves the cowboy’s hands and tightens around the rear legs of a running steer. I want you to feel the pounding of hooves go by as the cowboy jumps from the bucking horse to the pickup. I want you to see the soft, flexible body of the bull rider hit the hard back of the steer. I want you to feel the emotion in your throat as a thrown cowboy limps with his arms around the medics. I want you to taste mud on your lips as the barrel racer whips her horse around.

I want you to smell the leather.

But it’s not really possible, and that’s kind of the point. Before I showed up in Dawson Creek, I knew what a rodeo was. I knew what the pictures looked like. I didn’t know what it felt like. And I still don’t completely, but I’ve felt a part.

I climbed behind the bucking chutes to meet a few of the cowboys when it was over. Most were packing their gear, preparing to head off to the next rodeo. A few were talking about the steers’ bucking consistency. One of the cowboys had been caught on his bull until one of the bullfighters managed to dislodge him, so he had his jeans down to check a purple bruise that was already forming on his thigh.

I photographed three of the last cowboys, then asked if any of them would record an audio clip. A fourth guy, Scott, said he hadn’t been in the photo, so that meant it couldn’t be him. “No way,” said one of the others. “That means it has to be you!”

Scott was a bullfighter—in fact he’s the one in the black, white and yellow CERVUS shirt in the last rodeo photo. He told me he was originally a bull rider, but switched to having his feet on the ground when he got too tall.

I asked if there were bullfighter competitions. “There’s freestyle bullfights you can go and enter,” he said, “and it’s just you against a fighting bull. They mark you on the aggressiveness of the bull and how well you can stay with it. But that’s kind of a younger guy’s scoop. I’m mostly just cowboy protection.” He talked about watching the bull’s body language, being able to tell when a cowboy was going to get bucked off, and keeping the bull’s attention while the cowboy moved to safety.

Then I asked about the culture of rodeo and if it was going to continue.

“The future of rodeo is pretty bright. The kids we got now, they’re ultra talented, you know, they’re specializing at a very young age. We have a bit of a problem with the number of entries we’re getting, but the quality is totally there. I think that the future is, you know, we have maybe less kids going, but they’re a lot higher-calibre cowboys.”

Cowgirls, too.

I met Shaylayne on the raised platform above the chutes. She asked if I’d taken photos of the barrel racers and it took me a moment to realize she’d just been riding.

“My name is Shaylayne Lewis,” she said, “and I’m a barrel racer. I’m currently sitting fourth in the standings as a rookie. This is my first rookie year. I definitely plan on going to the Canadians Finals Rodeo and making it to the NFR, which is like the world’s finals.” She does 4-5 rodeos a week, and next year will do part of the American circuit and go to the finals there.

“It’s probably the scariest and most funnest thing I’ve ever done in my life. […] It’s humbling as well, because you know, like one day you’re on top, you’re so close, and the next day you’re way below, you know, things happen.”

Shaylayne was an athlete with a vision. She talked about her future, imagining rodeos paying her just to show up, the CFR in Edmonton putting her image on the billboards because they know she’ll draw fans, that kind of thing. I guess it was the kind of thing I’d hear from a preteen boy who dreams of playing soccer with the pros, except I’d just seen her click one of the rodeo’s top times on a borrowed horse. I believed her.

“I started barrel racing when I was four. I started racing with the pro girls when I was twelve. I did do highschool rodeo, but I hated it because I thought the girls were really mean.”

“And they were too slow.”

Through it all there was a sense of pride. Not the kind of pride that tramples on other people, but the kind that quietly polishes a belt buckle, or stitches beads onto a breastgirth. Everyone from the 13-year-old cattle rancher to the gritted-teeth barrel racer knew what they loved, and knew they belonged.

The last event was the chuckwagon races, which were more thunderous but less varied than the rodeo finals. The most significant part of the chuckwagon competition was the final race of Kelly ‘The King’ Sutherland, who was retiring after fifty years.

“Back in the mid-1960s a horse-crazy kid from Grande Prairie, Alta., headed down the road as a barn hand for chuckwagon driver Dave Lewis. By 1967, 15-year-old Kelly Sutherland was in the saddle and actively competing as an outrider. By 1969, Kelly Sutherland had moved up in the wagon box and hit the trail full time as a chuckwagon driver. The rest, as they say, is history.” Billy Melville, Thumbs Up to the King

The announcer, Les McIntyre, said what Michael Jordan did for basketball, what Muhammad Ali did for boxing, what Gordie Howe and Wayne Gretzky did for hockey; that’s what Kelly Sutherland did for chuckwagon racing. He’s won over a hundred major awards and victories and set nearly every record you could think of. “The name Kelly Sutherland,” wrote Melville, “became synonymous with chuckwagon racing over the last half-century.”

If you look closely at the photo, you can see him in the back of the white carriage. Eagle feather, thumbs up. A western Canada icon.

The crowd applauded Kelly Sutherland and the other winners of the rodeo. The kids gathered along the fence to chase a calf (catch his ribbon and win a bike) for the final event of the entire exhibition.

And with that, it was over. The bucking chutes were empty and the evening wind carried the distant sound of steers along with the dust of the stirred-up track. I followed the crowd back through the fairgrounds, past the boarded-up food stalls and the quiet midway. I checked for Brett near the auction house but his stall was empty, the ribbons taken down. The sky gave way to blue as the dusk gathered in the east.

And in that air of finality, I saw Miss Teepee Creek Stampede one last time. We shared a couple more stories and laughter and I photographed her in the orange glow of the stables.

In those final moments, I had a feeling that it wasn’t over. That the rodeo would continue on, in other communities across western North America and in years to come. Her crown was old, you see, a bit tarnished from stampedes gone by, but her belt buckle was new, with this year proudly emblazoned on it.

So next year there will be another, and maybe Brett will raise another steer or Shaylayne will win another race. Maybe Ruth and her partner will finish their quilt. Maybe that cowboy will get another bruise and maybe some chuckwagon racer will rise to take Kelly Sutherland’s place.

I won’t be here anymore. But the spirit of the West will be. If I’ve learned anything, it’s that it will always be.

For a photo essay on rodeo queens, check out Queens of the West in Matter. For a bit more about the training of young cowboys, read The Ride of Their Lives in The New Yorker. And on that note, if you have 15 minutes watch one of my favourite short films by Great Big Story, Pecos Tatum: Born To Be A Cowboy.