I had heard of the Oka Crisis, but I had never had it pointed out to me on a map. So when we bicycled through Oka on our way out of Montréal a few days ago, I wondered if it was the same place I had heard of. For me, the Oka Crisis was like the collapse of the Atlantic fishery or the Québec sovereignty movement—something I knew existed within Canadian history, but about which I didn’t really know much more than a few lines from a textbook.

Over the last few nights, I’ve read a bunch about Oka and there’s a few things I want to share. Not so much a timeline of events, because Oka was highly publicized and that kind of information is relatively easily accessible. Rather, a few things that I came across that felt important.

The land issue is still unresolved

Ellen Gabriel was a spokesperson for the Kanesatake Mohawk throughout the Oka Crisis and the events leading up to it. Five years after the summer of 1990, she said, “We’re still going to have to struggle for this land. Nothing has been resolved. Absolutely nothing.”

As far as I can tell, that remains true today. The federal government spent millions of dollars in the 90s acquiring land to create a contiguous land base for the community, but these Crown lands have not been transferred to the Kanesatake Mohawk, and the town of Oka still owns most of the forest that was at the heart of the standoff.

On the night before the police raid on July 11, Denise David dreamed of a deadly confrontation between her people and the police, and 25 years later, the memory still brought her to tears. “A lot of us have not spoken to each other about what we went through. We haven’t shared our pain or our stories,” she said.

“Still this land has not really been recognized by governments as ours. But for us, this is always ours. This is our land. We’re the ones who use it, who clean it, who take care of it. These trees spoke to us. We knew we did the right thing. No matter what we went through, we knew we did the right thing.”

Corporal Lemay had a sister

On July 11, the police attempted a raid of the blockade in Kanesatake. In solidarity, Mohawk warriors in Kahnawake blockaded Mercier Bridge, a vital commuter link to Montréal. In the conflict following this blockade, 31-year-old Corporal Marcel Lemay of the Québec provincial police was shot and died in hospital. It’s unclear who shot him.

He had a sister. I read about her in the Montréal Gazette. All she knew about Indigenous peoples, she had learned in a school curriculum that described their involvement in the Seven Years’ War and called them ‘savages.’

In 2004, she was asked to do an interview about the Oka Crisis, and in preparation ended up reading a history of the Kanesatake Mohawk. Days later, by chance, she listened to a group of Mohawks give a presentation in her church. Afterwards, she asked to speak. “Calmly, I thanked the group for making the trip and for the work they were doing. And then I apologized to the whole nation for the injustices they had suffered over the centuries, from the clergy, from the colonists and especially from the government. And then, after asking their forgiveness for the injustices, I identified myself as the sister of Corporal Lemay who was killed in Oka.”

“Despite my loss, I recognized their loss. And I can’t measure which loss is greater, which loss is more painful.”

It seems to me that the experience of Francine Lemay demonstrates the kind of compassion that is needed for healing to happen. It’s not simple, and it’s not easy. It takes time and effort and sacrifice. It requires listening.

An unarmed convoy was attacked

In the afternoon of August 28, some residents of Kahnawake began to evacuate in a convoy of about 75 vehicles ahead of the dismantling of the barricade. They were detained by the Québec provincial police, who searched them for over two hours while local radio stations broadcasted the location of the convoy. A mob of over 500 white vigilantes gathered on the far side of Mercier Bridge, where they called racist threats and threw rocks at the vehicles as they drove by, smashing windows and injuring the unarmed people inside. The police did not move to restrain the rock throwers.

An Elder, Joe Armstrong, was struck on in the chest by a large boulder, and died soon after of a heart attack. Women and children alike were traumatized by the vicious actions of the mob.

Oka was a turning point

Oka is commonly regarded as the first highly publicized armed conflict between First Nations and the Canadian government. It made international headlines, led to the Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples and was the model for continued resistance across Canada throughout the 1990s, as well as the Idle No More movement in 2012-2013.

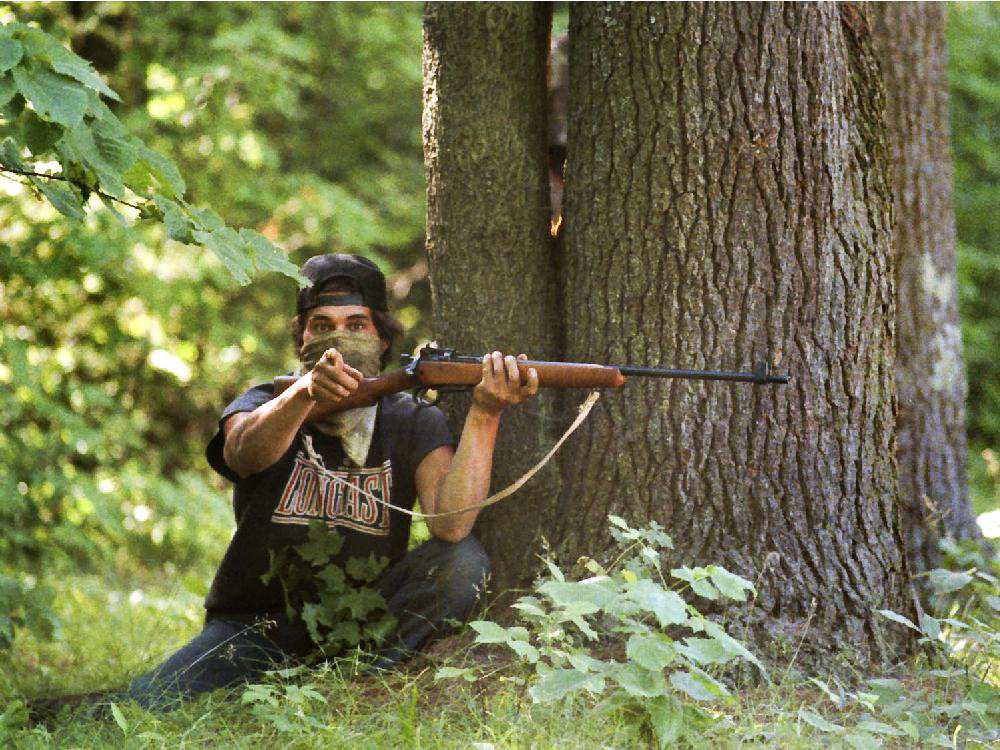

In 1990, the Oka resistance was led by the Mohawk Warrior Society, which had its origins in the late 1960s along with the urban-based Red Power movement in the United States. I found many accounts of how the Mohawks resistance provided inspiration to Indigenous people across the Americas, but Taiaiake Alfred and Lana Lowe explained it perhaps most eloquently. “Many people in the years following cited the Oka Crisis as the turning point in their lives, and the watershed event of this generation’s political life. Indeed, in terms of providing inspiration and motivation for the militant assertion of indigenous nationhood, the Mohawk Warrior Society’s actions in 1990 around Kanesatake, Kahnawake and Akwesasne stand alone in prominence in people’s minds and effect on the later development of movements across the country.”

“Young indigenous [sic] people in communities across the land saw through the Mohawks’ action that it was indeed possible to defend oneself and one’s community against state violence deployed by governments in support of a corporate agenda and racist local governments. Perhaps even more importantly, young indigenous people recognized the honour in what the Mohawks had done in standing up to what eventually were proven to be unjust and illegal actions on the part of the local non-indigenous government.”

I don’t think I know enough Indigenous history yet to fully understand this context or the decades following it, but it’s worth mentioning as a piece of the history of resistance to colonization, and one of the roots of the decolonization efforts that I’ve been a part of today. Oka was the ground zero of a new movement.

The last thing I want to share is a quote from Grand Chief of Kanesatake First Nation Serge Simon, who said simply: “Oka is what happens when dialogue stops.” As I’ve tried to demonstrate with this article, there are many pieces to the story of the Oka Crisis that are not well understood. There is the simple reality, however, that two men died, and many more could have. It makes me think of the words of a fellow activist after the standoff at Standing Rock this past winter, that we have to do everything in our power to prevent that kind of violent escalation here in Canada.

That doesn’t mean no blockades. It does mean showing up with our bodies to protect Elders and support grassroots organizers, and it means making space for ceremony. It means honouring the treaties. It means educating our young people about Oka and about the struggles that have followed it, so the next young person that cycles from Montréal to Ottawa won’t wonder. They’ll know.

And it means maintaining dialogue, with our neighbours and friends, with Indigenous leaders and with our politicians who are elected to represent us.

One of my most detailed reads was Oka Crisis, 1990 by Gord Hill of Kwakwaka’wakw First Nation. I also recommend People of the Pines: The Warriors and the Legacy of Oka by Geoffrey York and Loreen Pindera, or the 1993 NFB documentary Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance by Alanis Obomsawin. Photos from the Montreal Gazette and The Canadian Press.