I forget who it was, but someone in Inuvik suggested that I talk to Brian at Alestine’s for a perspective on local history and culture. Brian told me right away that he wasn’t an expert and that there plenty of people with more knowledge about Inuvik than he, but he was willing to talk about his community in the Arctic and the perspective he shared was thought-provoking.

“My name is Brian MacDonald. I’m from Inuvik, Northwest Territories,” he said. “We run a business called Alestine’s, a little restaurant. Born here all my life. Raised and born. About half my family was born here, the other half was born in Aklavik. Aklavik was where everybody settled, but then they created Inuvik for the reason, thinking Aklavik was going to sink. And so Inuvik was built.”

Aklavik, a hamlet on the Peel Channel of the Mackenzie Delta, began as a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post in 1912. For decades, Aklavik was considered the transportation, commercial and administrative capital of the western Arctic, but in the early 1950s the federal government, concerned about flooding and erosion in the delta settlement, established Inuvik on the hills above the East Channel of the Mackenzie River.

“My dad was originally a carpenter,” said Brian, “so he came over and helped build the town. He was the lead carpenter. He’d done security as they were bringing in the material from the south on the river, so he’d be here as security. Right where the restaurant is located, at that time they called ‘tent city.’ That’s where they started.”

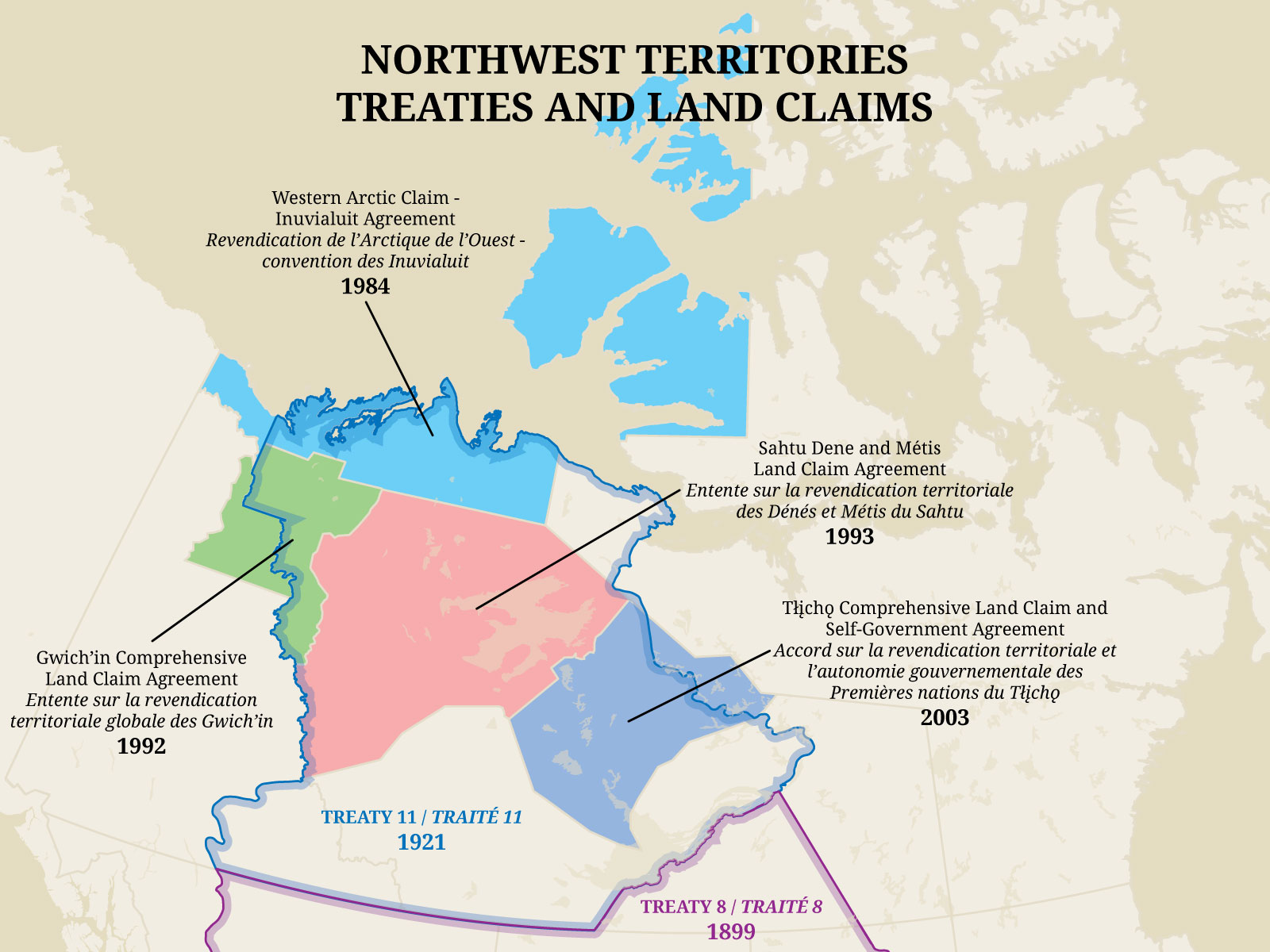

After talking about his family settling in newly built Inuvik, Brian referred to the land claim agreements that defined the region. After our conversation I independently researched the history of self-government in the Yukon, partly motivated by Brian’s firmness that understanding the land claims was fundamental to understanding Inuvik.

“You have the Inuvialuit, the Gwich’in, and the Sahtu, a little bit more southern. I actually belong to the Sahtu region, which is a land claim agreement. I belong to the land claim of the southern region. It would be better if I had a map.”

Brian’s mother was Sahtu. The logo of the restaurant is a photo of her, which I saw but didn’t photograph. Through her, and through the very fact of where he lived, Brian was part of the land claims history.

“It’s historical, in a lot of ways. There’s not a lot of places in this world that have, where a lot of the rights are given to the original people. They were the leaders, definitely the leaders throughout Canada.”

From Brian’s perspective, the land claim agreements of the western Arctic were looked up to in British Columbia and as far away as Australia. “The Inuvialuit were probably the first group in all of Canada that settled their land claim agreement. Up here is kind of the role models for all the rest of the claims that might be happening now.”

“A lot of it had to do with protection,” he added. “Everybody knows there’s a lot of oil, there’s a lot of minerals and stuff. I think it was trying to control, instead of people just flying in and raping everything or taking everything and just taking off and leaving leftover waste for people to deal with. I think they set it up fairly well, to protect the areas where they know there’s lots of animals. It’s rich in wildlife here. A guy could easily live off the land here if he wanted to.”

“People are very protective. I mean, you grow up somewhere all your life and you love the place, you don’t want to see all this stuff happen. It had a lot to with…totally protecting the environment was what it was all about.”

One of the most thought-provoking parts of the conversation with Brian was how environment and industry aren’t black and white. Brian loved the land and wanted to protect it. His family’s restaurant served local game as a staple on the menu, and he spoke about how much he valued that. But as a member of the Inuvik community, he also saw the economic stagnation that followed the withdrawal of the oil industry, and how much that hurt the people around him.

“Part of the economy was oil and gas, but the market doesn’t allow it, I guess because it’s cheaper to get it elsewhere. Which I’m okay with, because of all the problems that happens with resource development. The pollution and side effects. Environmental and social. The place is not…they were talking a huge boom, so the town would go to thirty thousand people from three thousand people. It would only last for a little while, then it would be all gone. So I was kind of opposed to that. It would be a mess after everybody left. Most of the employment would come from the south. They’d end up leaving, and what are you left with? If you’re a local, and you still live here, then you’re left with whatever the aftermath is.”

But at the same time, he said, “it’s kind of sad to see a community like Inuvik suffer. You know, there’s not much happening other than government. Other than that there’s not much economy-wise that’s happening. It’s kind of sad in that way.”

“But it’s for the future.”

One of the last things we talked about was climate change, and the effects being felt in the Arctic. Brian was matter-of-fact, but as I headed south back across the Mackenzie Delta and the Peel Plateau I wondered about the feeling of the earth literally moving beneath your feet.

“You start to see the changes, how the permafrost is sinking, creating these big, huge craters. That’s from permafrost, just collapsing, changing the whole landscape. It affects us but it also affects animals and stuff like that. Lots of changes, that’s for sure.”

The closeness of Inuvik’s history brought into clarity how young Canada really is. Aklavik, founded only 100 years ago. Inuvik, built by Brian’s father. Stringer Hall residential school, closed in 1971. The Berger Inquiry, 1974. The offshore oil boom of the 1980s. Climate change effects over the last decade.

You wouldn’t think the edge of the Mackenzie Delta in the Arctic Circle would be a place to find a sense of historical and national closeness, but there it was.

Map from Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre. For a brief history of the Northwest Territories, including a bit of what I learned about Prince Rupert’s Land while researching Louis Riel, visit Territorial Evolution of the Northwest Territories. Also, I found out that Aklavik calls itself, ‘home of the barrenland grizzly,’ and it didn’t fit in the article but I love that.