We met Sid Bobb in Nipissing First Nation west of North Bay, ON, and sat with him around a community firepit while wind blew off Nipissing Lake through the trees above us.

“You’re in Nipissing Anishinaabe territory,” he told us. “This is often called called Duchesnay, but it’s part of the ancestral territory of a number of families. We have Big Medicine Studio here. It’s owned and operated by myself and my wife, Penny Couchie, who’s the other co-artistic director of our company, Annmitaagzi, which means ‘He/She Speaks’ in Anishinaabemowin. This specific region was home to a lot of ceremonies for the Nipissings, so we hope that this studio and our yard contributes to that ongoing saga of activities.”

“My name is Sid Bobb,” Sid continued. “I’m the son of Lee Maracle from Tsleil-Waututh First Nation in North Vancouver, the People of the Inlet. My dad is Ray Bobb from Seabird Island, that’s part of the Stó:lō, the People of the River. Salmon people on both sides.”

“I’m not a Nipissing First Nation member,” he added, “but I am a community member by marriage. We have a daughter who’s twenty-two, Nimke, and my son, Osk, who’s entering his time as an adult, he’s eleven.”

According to the Aanmitaagzi website, Big Medicine Studio is the only dedicated arts studio of its kind in the region. “Built as a home for the creation, development and exhibition of performing and visual arts, it is a place where community comes together to celebrate and engage in arts and culture.”

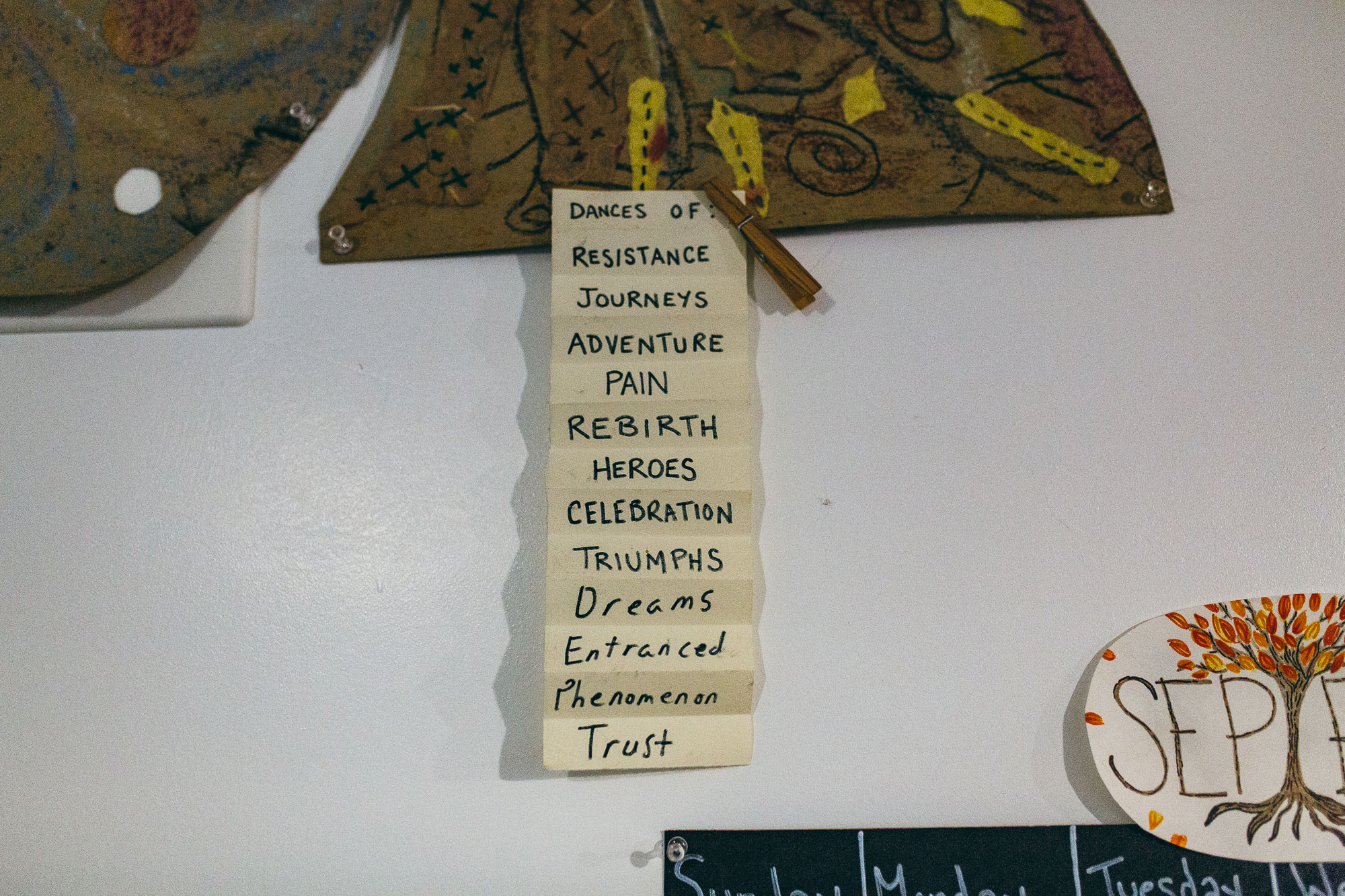

Sid talked about the integration of family, personal and spiritual practices in Aanmitaagzi. “We go from bush to table to stage. We harvest as much as we can as a company, and then we process that stuff, whether it’s hides or meat or syrup or fish, and then make it into art. How we engage with that sustenance materializes in different ways from that process to songs and poems and books and dances.”

Trauma and healing are intrinsically part of the work and artistic practice of Big Medicine Studio. The studio has existed for almost ten years. The process of healing has been ongoing for generations.

“This recent play that we did, we asked these youth what they hear in the story and what stories do they want to bring forward, and there were a lot of stories of, you know, family violence, sexual violence, alcohol abuse, prescription abuse as children, with a lot of the dialogue around residential school and Canada 150. That seems to be what comes to the front, all these things that have challenged individuals in their own lives.”

“We have historic trauma, but we also have ongoing trauma that continues from that cycle of violence. Until we address that trauma, and learn to manage and deal and process that trauma, some of the accompanying ways of coping with it, like alcohol and substance abuse, will be very difficult to overcome.”

Sid referred to violence and abuse in his past life, but gracefully focused on the present. “As soon as you, if you get up on a life raft, and you get out of trouble, and you’re economically and spiritually stable, your job is to extend your hand to others.”

He was silent for several seconds, his eyes shining in the forest light. “Every now and then these feelings come up.”

“I often remind youth that we have a red road. The red road is the path that we walk to be good human beings, and we do that together.”

Sid continued, “Here in Nipissing, they have this welcoming baby ceremony, and the community gathers to see the new babies in the spring that have come from the previous year. And they say it’s so good to see you.” Again his eyes filled with tears, and he took several deep breaths. “It’s a really powerful ceremony.” More deep breaths. “I guess I dream of helping to create space for all children to benefit from that idea, and from that richness and strength that comes from people and community committing to seeing the beauty of a human being.”

“The adults gather and they see the babies, and they commit to providing them with whatever they need on their journey. I think that's the red road that I'm committed to, and that art is here for.”

“Art is at the heart of our gatherings; singing, dreaming, visioning, dancing, making. So that’s what this studio is for. It’s a place where people can gather and be seen and be heard, and hold each other up.”

Sid connected art to Indigenous resistance, as well. “I think that’s what’s been intentionally shattered by the federal government,” he said, “through residential schools, through the banning of the potlatches, through the outlawing and prohibiting of our dances. It’s interrupted and destabilized our red road, you know, our idea of who we are and what we’re here for.”

Big Medicine Studio stands in resistance to that, an ongoing act of reclamation and resurgence. As Sid talked, a couple of young people wearing jingle dresses walked out of the studio. “You can hear it in the background, the beautiful bells,” said Sid. “Those bells, they call our ancestors, they invite our ancestors to come and join us. The jingle dress is a healing dress. And ‘Big Medicine’ is in acknowledgement of what they used to call the Nipissings: Big Medicine People.”

“I think we have a lot of healing on our hands, to various degrees, but I also think the threat and violation of our human right to exist as we choose; that threat and violation is still present.” Sid spoke about the Athabasca River and Lake Nipissing, and the potential damage of the Energy East pipeline. “I would imagine if you asked most Canadians if healthy, sustainable water is a value of theirs, I would imagine they would say yes. So then I guess we have a shared value as Canadians.”

Sid pointed out that that value was undermined by Justin Trudeau’s industry politics. “I’ve heard him in the media saying that we can have both the environment and the economy. But the economy he’s proposing is not in line with what most Canadians value.”

Healthy, sustainable water becomes a lot clearer when you’re sitting beside a windy lake.

“I fantasize about healthy bison populations, healthy salmon populations and berry populations. So I already know that Indigenous communities haven’t ‘had both’ for a long time. The Cree from the Plains haven’t had bison roaming as they had for quite some time, the east coast, they don’t have their wild salmon anymore and our wild salmon out west are dwindling. ‘We can have both’ is a powerful idea, but a lot of Indigenous communities haven’t had that.”

“The other question of that is, well, the healing of Canada. I think if Canadian citizens want to bring themselves closer to their values, then they also have to face that threat. Otherwise you're a sick, predatory nation—which is what I think of Canada as a country, both on the environment but also on the exploitation of people. If we want to match that Canadian flag there's a lot of change that needs to happen.”

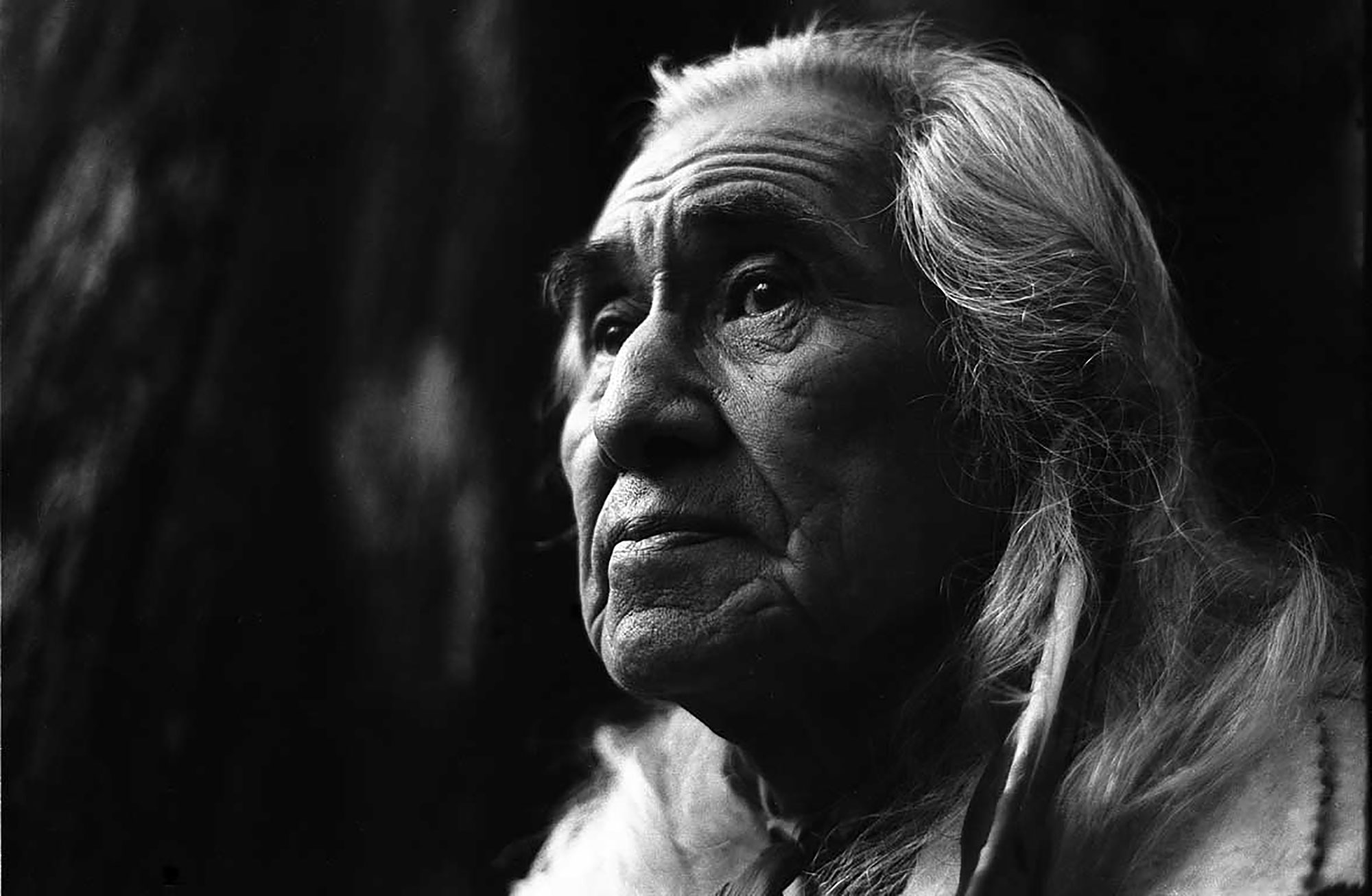

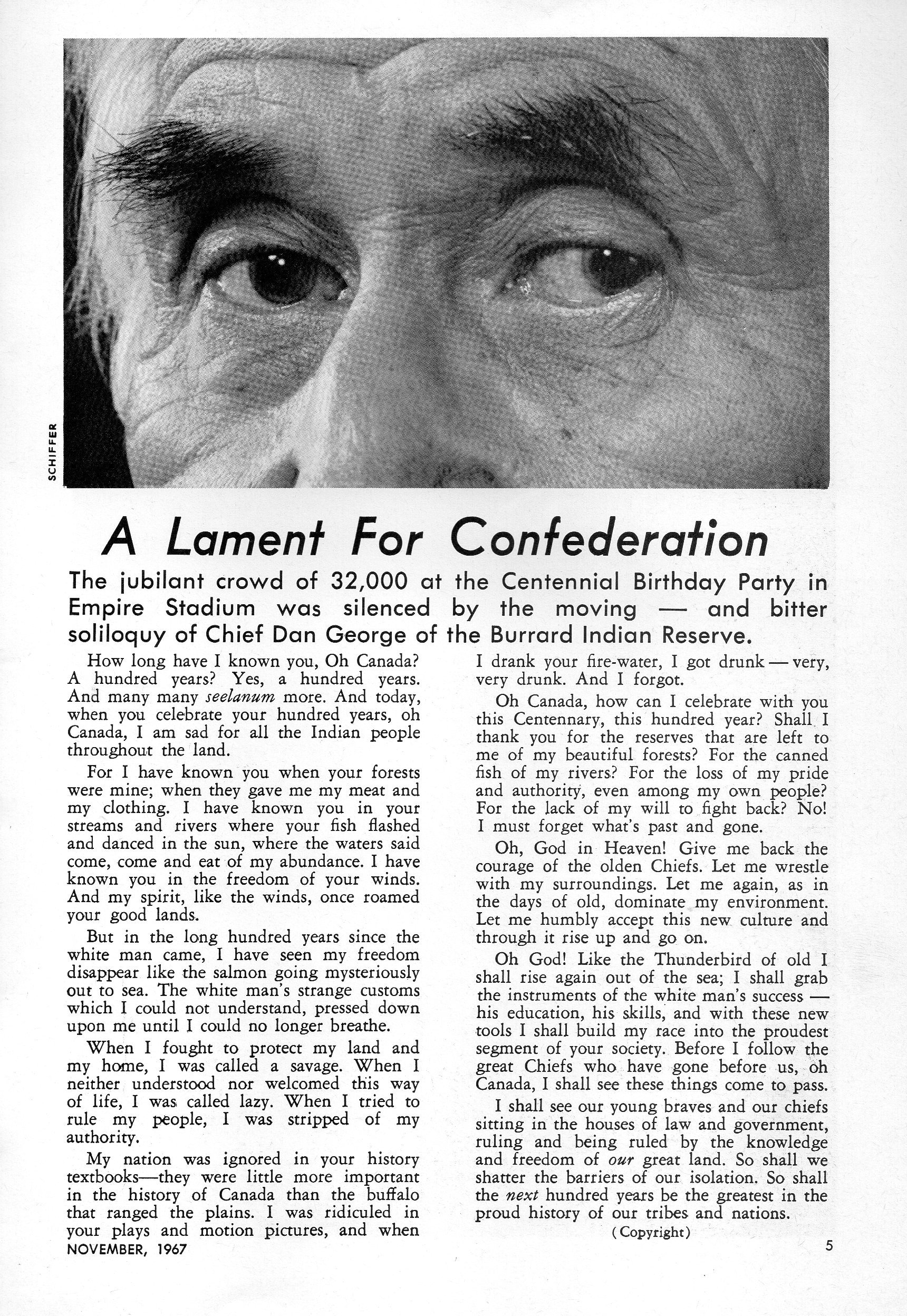

Back in July I wrote about Chief Dan George’s Lament for Confederation, a poem and call to action that he wrote and performed in 1967. I found out about Dan George because he was Sid Bobb’s great grandfather.

Sid said he was too young to really know Dan George, but he knew his songs and his works. “When I first heard the Lament, it just…emotional overload. It brings everything to the fore in such a way. Because we still have that. We still have heartwrenching rates of alcoholism, heartwrenching rates of substance abuse.”

He was quiet for a long time. “You know, I grew up in Vancouver. Seeing so many people, you know, drinking or shooting up on the streets. Seeing our beautiful drums in pawn shops, it’s just so saddening to see. To hear the amount of youth who commit suicide, you know, or get addicted to such harsh drugs. It can be very depressing and saddening. So to hear that Lament, it struck me as well, losing cousins or friends and family. We all hear these stories of communities who continue to lose their loved ones to suicide or to substances, overdoses, and I imagine that we have a long road in front of us.”

“The mechanisms, the violation of our rights and our communities, those don’t seem to be going away any time soon. The murdered and missing Indigenous women, the children being taken by CAS, the self-abuse, the lateral violence in our communities, the violence from the outside. That colonial legacy is an ongoing animal.”

But the legacy Lament for Confederation wasn’t just a recognition of ongoing colonization and violence. Sid met that reality with a vision for hope that echoed from Dan George’s words to his own.

“But also the richness of hope in the Lament, about the dream for the strength of ‘the olden Chiefs’ is so awesome. It’s so great. I hope to have that strength and wisdom, and I strive for that; because if every family can have that strength and passion and understanding and hope, then our future for our kids will remain bright.”

You could feel where his words were coming from, you could almost see them beating from his chest to his voice. The loss was there, in his heart, but the hope was too.

That’s when Sid’s eleven-year-old son Osk came and sat near him, and while I was watching Sid’s heartbeat I started thinking about blood, and generations, and change. Dan George lived in Sid, and now in Osk. “Give me back the courage of the olden Chiefs,” Dan George wrote in 1967. “I shall see our young braves.”

The last part of our conversation was about Indigenous manhood. “I think Tracy Byrd, maybe I’m getting it wrong,” started Sid. “She’s a Cree, she was on CBC, she was saying how it’s important to say, when we talk about violence against Indigenous women it’s colonial violence against Indigenous women. It was systemic, it was planned. When you destabilize a community, you can steal their resources.”

“I have to remind myself that male violence—lateral violence, sexual violence, physical violence—that’s an intentional thing meant to destabilize our communities so that people can exploit this land.”

“When I look back on who did I talk to about what is it to be a man, how do you feel, what is it to be a father, I don’t recollect having a lot of conversations with anybody.” He looked at Osk, who was gazing back at him with all the quiet pride of a shy eleven year old. “So I want to make sure that my son has the opportunity to have these ceremonies and teachings which allow him a platform to investigate who he is.”

“If we’re to unravel patriarchy and colonialism and capitalism, there’s a lot of work that men have to do to balance it out.”

I wonder if this interview seems imprecise or disorganized, but I think it speaks to the interconnectedness of justice in Canada, a sense of connection that gradually became clear as I crossed the country. Art is connected to healing, which is related to colonization. Environmental exploitation is connected to violence against women, and both of those things are part of capitalism. And through it all, Dan George, born in the 19th century, is connected through Sid to Osk, a child of the 21st.