The name Louis Riel stands out in Canadian history, and ever since I rode past the Manitoba Métis Federation building in Portage La Prairie, MB, I’ve been planning on learning a bit more about him. This isn’t an exhaustive exposition on Métis historiography; these are just a few things that I learned after a couple days of reading.

The Hudson's Bay Company was the world's largest landowner

Since its royal charter in 1670, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) held legal control over ‘all lands whose waters drained into Hudson Bay,’ also known as Prince Rupert’s Land. The area covered four million square kilometres—over one-third of the area of Canada today.

The resistance that became known as the Red River Rebellion and the birthplace of Louis Riel as a leader originates with that HBC land holding. By the mid-19th century Métis traders—including Louis Riel’s father—had been in conflict with the HBC for decades over trading privileges. With the HBC’s 1869 surrender of Prince Rupert’s Land and North-Western Territory to the nascent Dominon of Canada, however, migration from the eastern Canada led to heightened tension in the Red River Colony.

“During the lengthy negotiations to transfer sovereignty to Canada, Protestant settlers from the East moved into the colony, and their obtrusive, aggressive ways led the Roman Catholic Métis to fear for the preservation of their religion, land rights and culture. Neither the British nor the Canadian government—with no appreciation of the Métis people—made any serious efforts to assuage these fears, negotiating the transfer of Rupert’s Land as if no population existed there.” J.M. Bumstead

William McDougall, one of the ‘Fathers of Confederation,’ was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory. He travelled west to re-survey the land occupied by the Métis, but his entry to the colony was blocked by Louis Riel and the newly-formed Métis National Commmittee. Riel was elected secretary of the Committee, and later president of its provisional government with the Declaration of the People of Rupert’s Land and the North-West.

The Red River Rebellion was not the end

In brief, the 1869-70 uprising in the Red River Colony helped form the new province of Manitoba but was brought to an end by a Canadian military expedition meant to confront Louis Riel, as well as counter American expansionism. Knowing that he would be arrested and probably lynched, Riel and his followers fled to the United States.

I knew vaguely that Riel spent some time in exile, but I thought this was more or less the end of Riel’s historical significance. It wasn’t. He fought again on behalf of the Métis in the North-West Rebellion fifteen years later.

The Manitoba Act of 1870 had guaranteed the rights and land titles of Métis people, but by the 1880s many of them had migrated from Manitoba to the Northwest Territories in response to the mismanagement of those rights. In 1884, the Métis asked Riel to return to Canada to organize the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan, hoping to influence the Canadian government in the same way they had in 1869. At the same time, the Cree, Blackfoot and other First Nations of the Canadian Prairies rose up against the federal government in the face of bison extirpation and broken treaties.

I’m not going to go into detail about the events of the unsuccessful uprising. The point of mentioning it is that the Canadian government failed so completely at upholding their commitments that thousands of people were forced into migration and armed rebellion in order to protect their rights and lives.

Riel demanded a political trial

After the defeat of the North-West Rebellion at Batoche, Riel surrendered himself to the Canadian militia and was charged with treason. From what I knew, he pleaded insanity. What I didn’t know was that the insanity defence was without Riel’s consent.

Riel’s lawyers were paid for by his friends in Québec, and their priority was keeping him alive. But, as George Stanley put it, Riel understood that an insanity plea would discredit his people’s legitimate grievances against the Canadian government. Instead, Riel wanted to pursue a claim of self-defence in order to justify the Métis actions in 1870 and 1885.

In his final statement, Riel drew the jurors’ attention to the shortcomings of the federal government and its inaction towards the petititons of the Métis and Indigenous peoples. He described their aggression towards him and his people.

“The Ministers of an insane and irresponsible Government and its little one—the North-West Council—made up their minds to answer my petitions by surrounding me slyly and by attempting to jump upon me suddenly and upon my people in the Saskatchewan. Happily, when they appeared and showed their teeth to devour, I was ready: that is what is called my crime of high treason, and to which they hold me today. Oh, my good jurors, in the name of Jesus Christ, the only one who can save and help me, they have tried to tear me to pieces.” Louis Riel, Final Trial Statement, 1885

He finished by saying that if anyone had committed treason, it was the entire government of Canada.

The July 31 speech was Riel’s last attempt to stand up for his people. In doing so, he intentionally unravelled his lawyers’ insanity defence. The result was simple. With tears in his eyes, the jury foreman read the verdict to the courtroom: guilty, with a recommendation of mercy. But there would be no clemency, and on the morning of November 16, with the final words, ‘courage, Father,’ to a weeping priest, Riel was hanged. A week later, six Cree and two Assiniboine warriors were hanged as well.

“We must cherish our inheritance. We must preserve our nationality for the youth of our future. The story should be written down to pass on.” Louis Riel

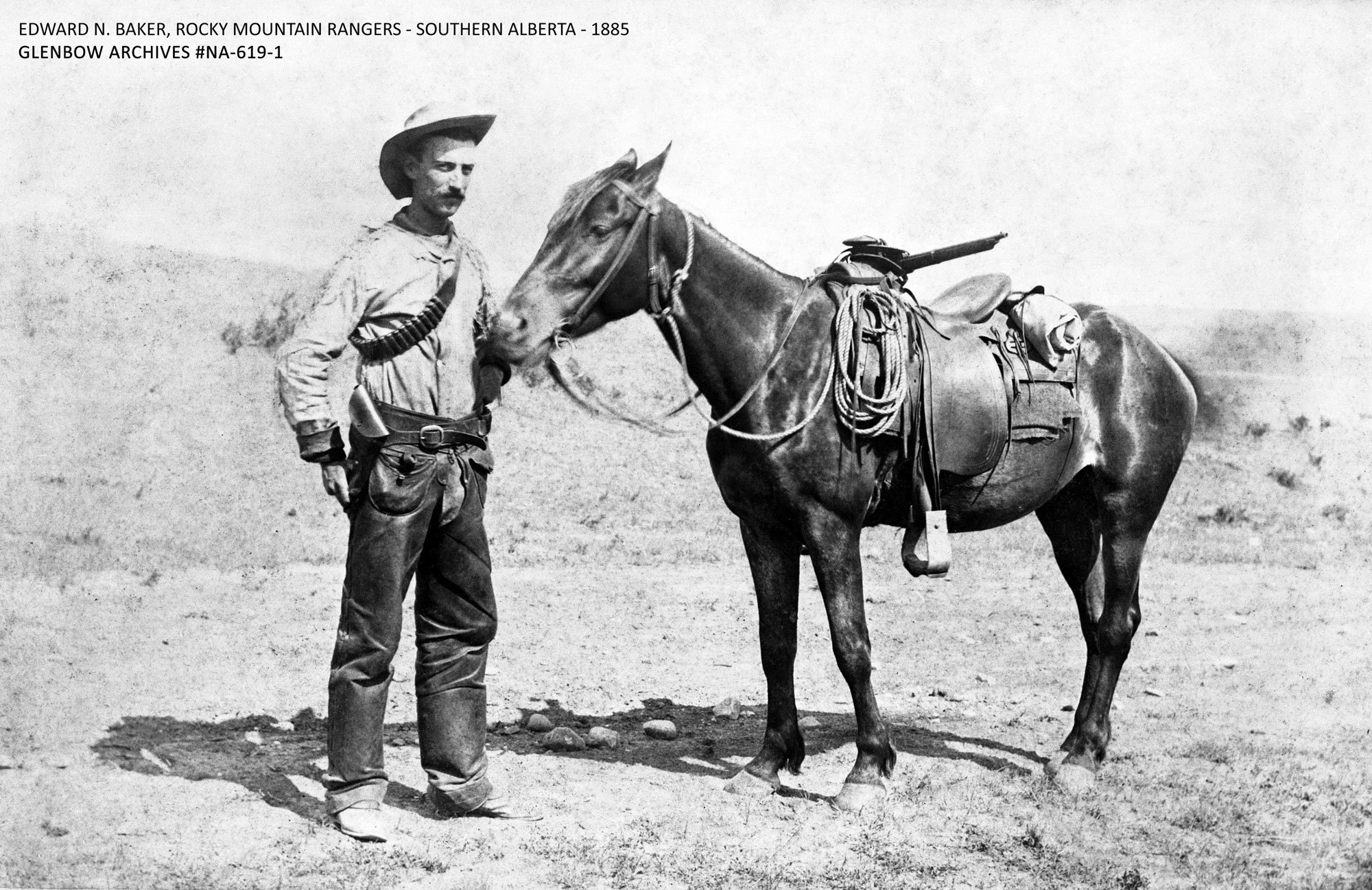

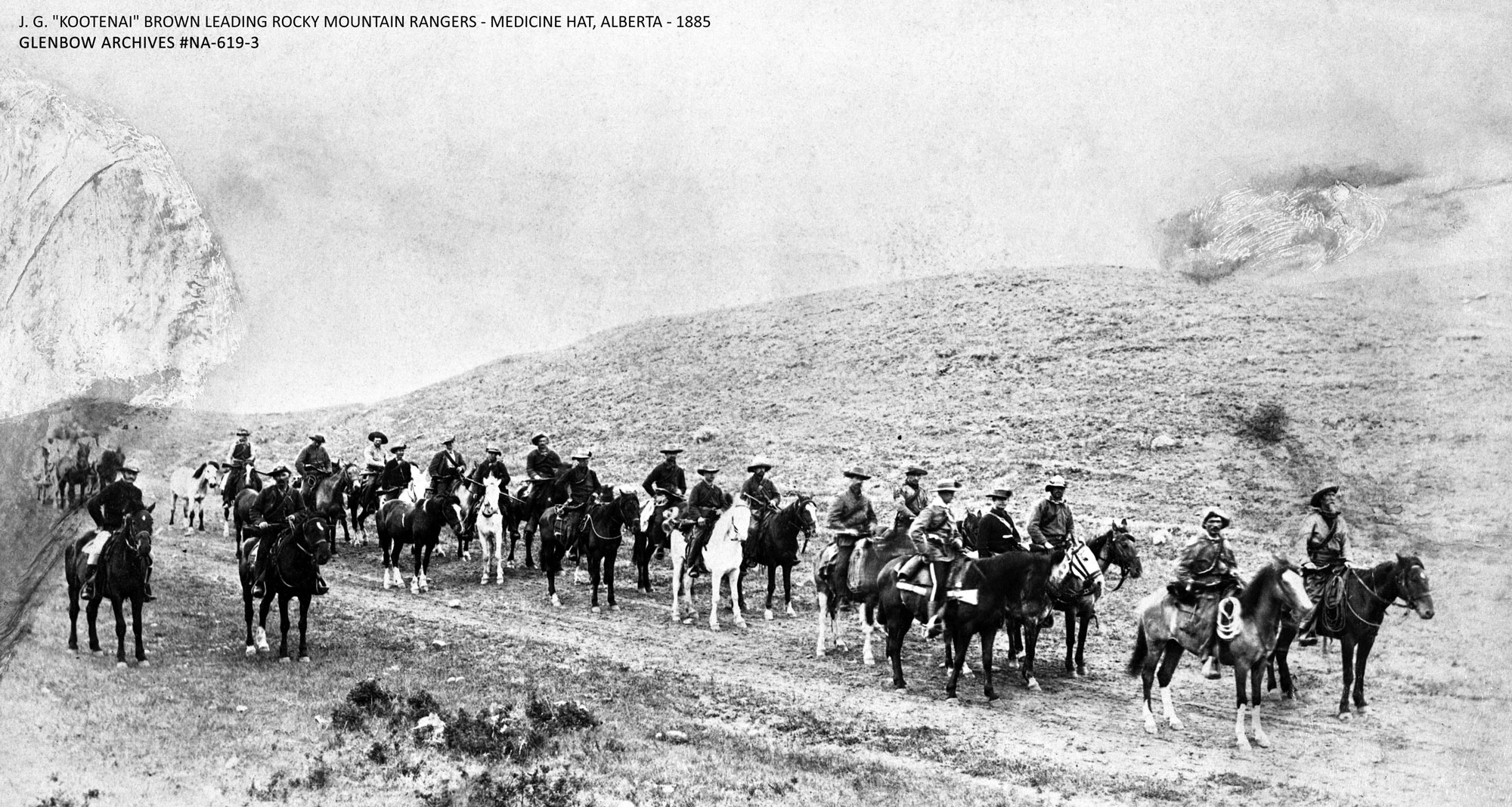

Photos from the Archives of Manitoba and Galt Historic Railway Park.