While we were in Winnipeg, we cycled up to St. Mary Ave. and Memorial Blvd. to get a tour of the provincial archives. We’d seen but hadn’t visited the archives in St. John’s and Fredericton, so we were privileged to meet with Mary, one of conservators of the Archives of Manitoba and the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives.

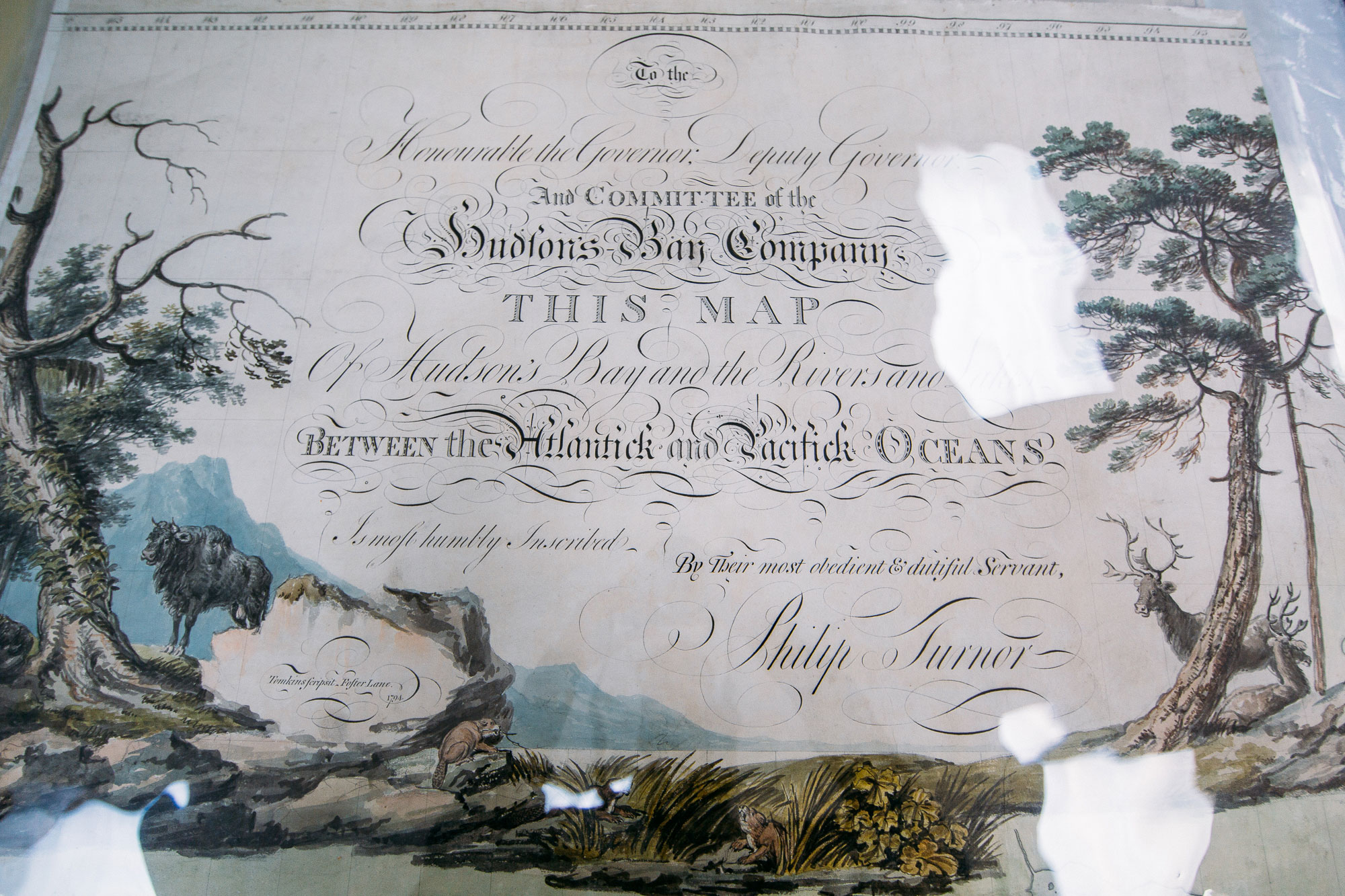

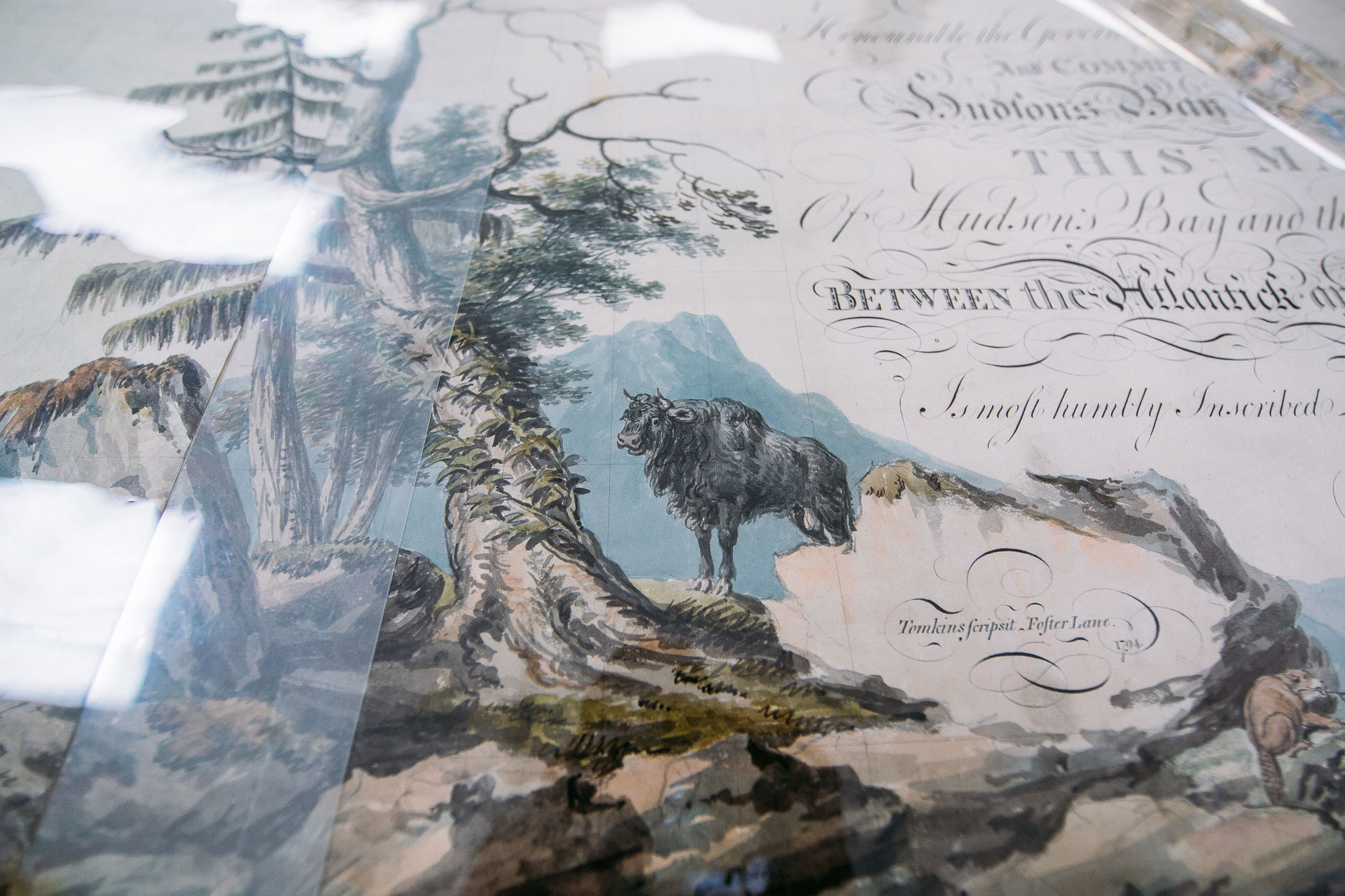

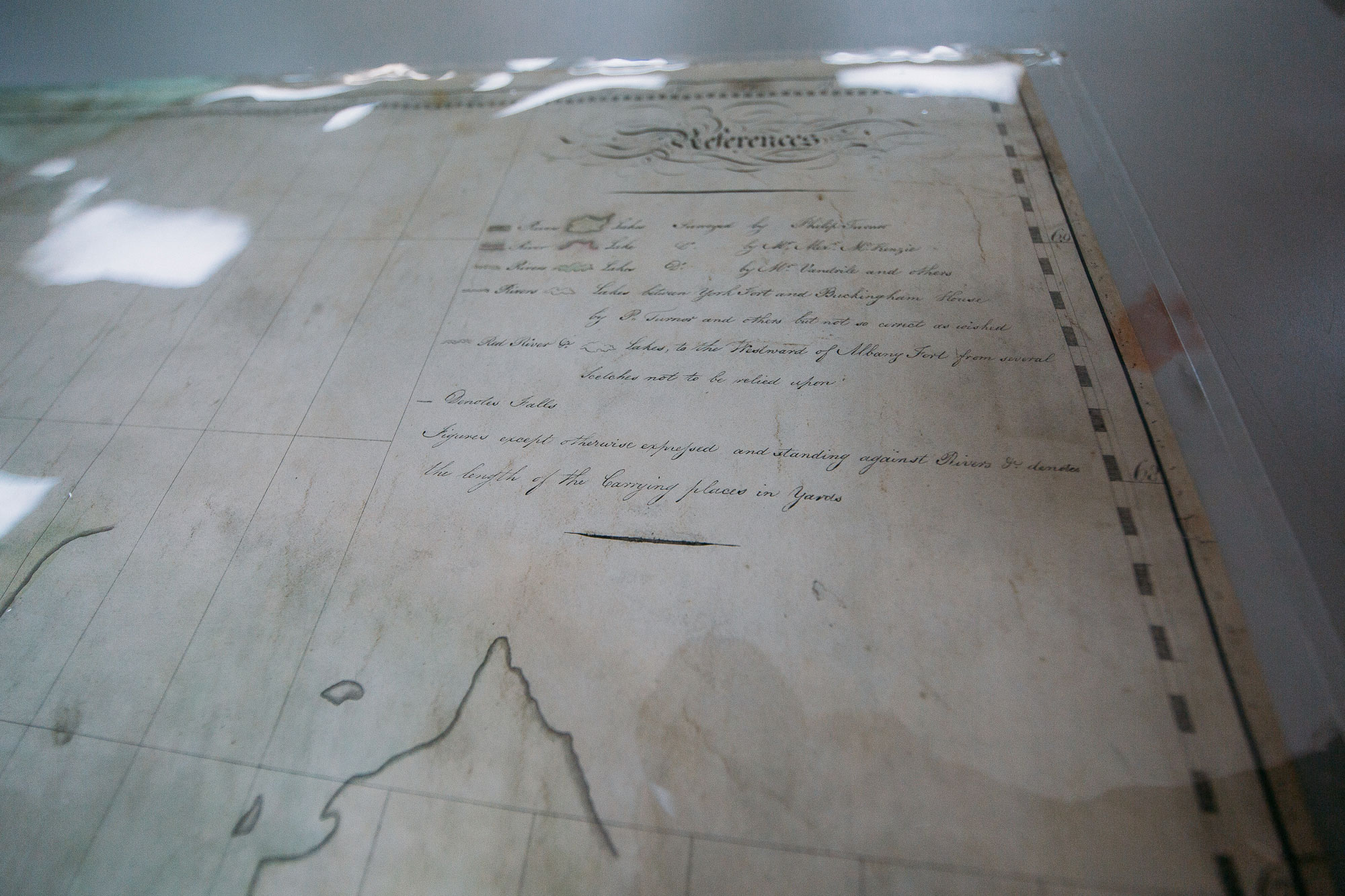

The biggest piece of work being undertaken in the lab was a 9x7' Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) map from 1794. The cartographer was named Philip Turner, with information sourced from surveyors working for both the HBC and the North West Company. HBC surveyors were marked in black, whereas other sources were marked in light grey because they were less trustworthy. When the map was created, it was the most accurate map of what is now Canada, with all the most accurate surveying that they had.

“You can see how there were big cracks,” Mary pointed out. “So we decided it needed help, and we took the backing off. We had to cut off the tubing, we flipped it over and took off the sail cloth, and then we found a layer of paper that needed to come off, and then there was another layer of paper that needed to come off before we got down to the base layer of map. The bottom part was covered in silk to try to consolidate all the flaky bits. That was a bit of a fun time trying to get that off. It was very,” she paused with a bit of a grin, “tenacious is the word I’m going to use.”

“Eventually we got it to come off, and we washed it to lower the acidity of the paper so it was less brittle and to help get some of the centuries of dirt out of it. Then we put all the pieces back together.”

This kind of work can only be done in the summer because winter in the Prairies is too dry, and this was the third summer they were working on it. It’s hard to imagine the attention to detail, commitment and hard work that is involved in the process of restoring a 200-year-old document over the span of several years; but there it was, under my fingertips (protected, for the record, by a plastic sheet).

I only really photographed the cartouche, because the rest was rather blank. I wish I’d photographed the map, though, because it was funny and interesting to look at the inaccuracies of 18th-century surveying, which seemed to involve a lot of guesswork.

Mary pointed out the long-haired cow on the left side of the cartouche. “The artist was European,” she explained, “and he’d never been to North America. This might have been his idea of a moose.”

The biggest reason I kept this audio clip is because you can hear the passion in Mary’s voice. You can hear how energized she is by the history all around her. It’s tactile. It’s tangible. And it’s her job to protect it.

I asked her why she thought history was important, and her answer was simple.

“The past is who we are. Without the past, how are we supposed to move forward, like how do we learn from our mistakes? We will just keep repeating them if we don’t know what they are.”

I’ve done a lot of research throughout this project, and I know that a lot of that research has been possible because of the work by dedicated conservators, historians, archivists, archaeologists and every other profession involved in the discovery and preservation of history. So this is an acknowledgement of gratitude, as well as an amplification of why history matters, from someone who works on it every day.