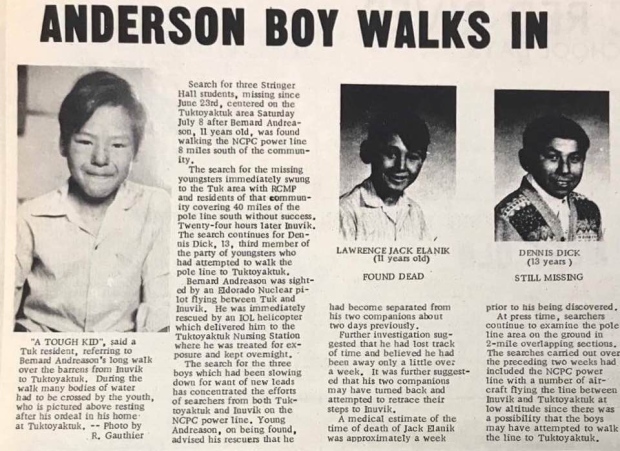

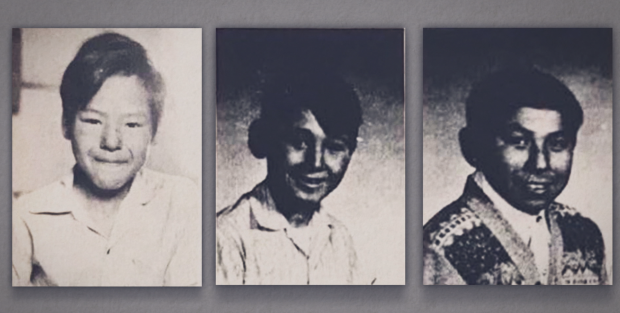

I heard while in Tuktoyaktuk that a local is advocating for the new highway between Inuvik and Tuk to be named ‘Freedom Road’ to commemorate three boys who in 1972 ran away from residential school in Inuvik. Bernard Andreason, age 11. Lawrence Jack Elanik, age 11. Dennis Dick, age 13. Bernard was the only one to survive after being found eight miles south of Tuk with swollen feet and having lost 30 lbs.

I read about them in a CBC article in August, but just recently came across an interview with Bernard Andreason—in September 2017. In my head, June 1972 was a long time ago. It’s not.

The escape attempt began after they smoked some stolen cigarettes in the hills behind Stringer Hall. “We were scared to go back,” said Bernard. “We didn’t know what was going to happen. The supervisors weren’t very nice people. They were really mean toward us—so mean that we were scared of them.” So instead of going back, they tried to return to their homes in Tuk and Sachs Harbour over 150 km of permafrost and river delta.

After a few days, rain set in and they reached a large creek that they couldn’t cross. “That’s when Jack started not feeling well. He started getting sick, crying all the time.” Dennis decided to press on while Bernard stopped to rest with Jack. Bernard never saw Dennis again. He spent the night huddling with Jack, trying to keep him warm as a storm blew over. In the morning, Jack was too weak to get up.

“I tried talking to him,” recalled Bernard. “He couldn’t talk, he was just crying…I didn’t know what I was going to do. He was too sick to get up anymore.”

In the end, one 11 year old had to leave the other. Bernard walked another two weeks by himself, following power lines and crossing waist-deep lakes and rivers, and hallucinating from exhaustion. When he reached Tuktoyaktuk, he was flown to the hospital in Inuvik, where he received the news that Jack’s body had been discovered by a search and rescue team.

“I went crazy, I couldn’t sleep, and I felt really bad. I was too young to know about death and stuff like that.”

Jack’s sister called the story that the boys had run away for fear of the consequences of the stolen cigarettes a cover-up from the abuse, and Joe Nasagaluak, the local behind the name ‘Freedom Road,’ echoed her sentiment. “They weren’t running away for stealing a pack of cigarettes,” he said. “There was something more. They were fighting for their lives, to reach home, for freedom.”

I sought some more stories of residential schooling in Inuvik and that’s how I discovered the story of Abraham Ruben in We Were So Far Away: The Inuit Experience in Residential Schools. He was a student at Sir Alexander Mackenzie School in Inuvik through the 1960s.

Although it’s a brief digression from Abraham, I also read the testimony of Marius Tungilik and was moved by his description of his childhood before being taken to residential school in Chesterfield Inlet: “I have some very fond memories of my childhood. Before I went to school I was very carefree as far as I remember. People used to talk to me in terms of endearment all the time; cutie, or—I don’t think they ever called me by my real name: Marius. But then it was always ‘my wonderful son’ or anikuluk. It was always something to do with something wonderful.”

Abraham’s memories of residential schooling are in large part defined by a nun, the ‘headhunter in Aklavik.’ He woke from nightmares about her his first night to find that he had wet the bed, and when she saw him there she dragged him to the floor and started beating him. He fought back and she hit harder. From the teachings of his parents, Abraham said he believed in the existence of evil spirits. “Humans as well as beings in the spirit world have the ability to become malevolent in nature and malevolent in intent. Here I am, a seven-year-old boy and I realized that this thing that has come into my life, from my understanding of my Native background, is that I’ve stumbled across an evil spirit in the form of this woman, this Nun. And that she would be a part of my life for years to come.”

He said she was brought in to the school because of her ability to break people. “Within a few months or a few weeks she could take a kid who spoke Dene, G’wichin or Inuvialuit and they would stop and start learning a whole new method.”

“My mother and father had often taught me to always resist being taken in by this type of spirit,” said Abraham in his testimony, “because it will devour you.”

And so he held out for years, throughout his childhood. Trying to maintain his language, his memories of his parents and his home. Even as his cousins gave up keeping their language, even as the nun set other kids against him. Through multiple kinds of abuse. By age 15, Abraham was addicted to alcohol, which he fought with throughout his young adulthood as he struggled to become an artist and reconcile with what he had experienced as a child.

“Whether the story is told once or a thousand times,” he concluded his testimony, “it still has to be told.”

That’s why I’m sharing this. Because the stories need to be told.

Today, September 30, is Orange Shirt Day. Orange Shirt Day is a legacy of the St. Joseph Mission residential school commemoration held in the spring of 2013. It grew out of a woman’s story of having her shiny new orange shirt taken away on her first day of school at St. Joseph, and it has become an opportunity to keep the discussion on all aspects of residential schools happening annually.

The end of September is the time of year in which children were taken from their homes to residential schools. In each of the testimonies in We Were So Far Away, I read about children returning to their homes and parents and communities to run free for the summer, to reconnect with their culture and land—only to be taken away again at the end of the summer.

Taken back to evil spirits.

The point of this is that children matter. They mattered 45 years ago when Bernard lost his friends. They matter today when communities combat youth suicide and the effects of intergenerational trauma. But I’ll conclude with these photos from a community event in Inuvik, because facing the history of residential schooling can feel paralyzing. It’s huge. It’s heartbreaking.

I found out that this fire pit in Chief Kim Joe Park was built for the second national Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearing in 2011, which saw over 1,000 residential school Survivors convene in Inuvik to tell their stories and to begin or continue the process of healing. When I was there a month ago, the fire pit was being used to offer free hot tea to community members, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike.

“Yeah, I think it matters that the fire pit was built as part of the TRC,” the woman serving tea said to me, “but this fire isn’t reconciliation.”

“I think what matters is the coming together of people. The whole community is out here, and that’s where you begin to have conversations and relationships. That’s where reconciliation begins.”

So today is Orange Shirt Day, a day to have conversations about residential schooling and to keep the reconciliation process alive. I encourage you to read resources like Legacy of Hope, We Were So Far Away or We Matter. But more than that, I encourage you to take the time, in person, to join a community event or have an eye-opening conversation. We are all part of the process of healing from residential schooling.