The Skidegate Youth Center is in a longhouse beside the ocean. I met Willie when I stopped in on a rainy afternoon and found him neatening up and getting ready for the kids. While we talked he moved around the space, picking up items and putting them in places where they belonged. After a bit, I let him continue with his work, but I promised to come back the following night to see the youth centre in action.

If you’ve ever been to a youth centre, you probably know the sights and sounds at Skidegate. Kids leaned their bikes against the wall outside and walked through the open door. They lounged on the couches or flipped through the wetsuits beside the windows. I could hear basketballs bouncing on the pavement outside and a whirlwind of conversations from the different rooms. I sat on the floor with an 11 year old braiding my hair until another kid pulled my hand. “Come swimming with us.” We headed out to the ocean. The sun went down. Kids gradually left for dinner and homework, riding their bikes under the streetlights past the longhouse. Eventually, it was just me and Willie. I helped him clean up and then we sat beside each other on the couch. The youth centre was still and quiet.

“I am William Russ,” he said, “and we are in the Hiit’aganiina Kuuyas Naay Youth Centre, which means ‘Young People Precious House,’ in Skidegate, British Columbia. I’m the head youth worker in this building.” He told me the youth centre was built in 2012 and opened for a summer, but then stalled while they looked for coordinators to run the programming. “It’s been open since 2015 and so we’ve been going strong since then, getting funding and finding different things to do with the kids and just building the program up into what it is now.”

“We focus on the kids, and let them lead what’s going to happen. And so they get a sense of this place as being theirs.”

The youth centre doesn’t just have Indigenous kids, but traditional teachings and Indigenous culture are a big part of their focus and programs. Willie and the other staff coordinate with the Rediscovery camp, the Skidegate Haida Immersion Program and the Youth Assembly of the Council of the Haida Nation, as well as local Elders and mentors to connect youth with the land, with their culture and their community.

They run traditional skills programs when they get the chance. “We get deer donated to us from different community organizations, so we teach the kids how to skin the deer, how to debone the deer and then how to process it into finished, jar product that they could save for the year. Not only deer; we also do salmon, we go crabbing, we are going to go gather wild cranberries, we get Labrador tea, just anything that has to do with outdoor activity or gathering from the land we do. It’s just programs that we try to come up with local people, so they can teach their skills to the kids.”

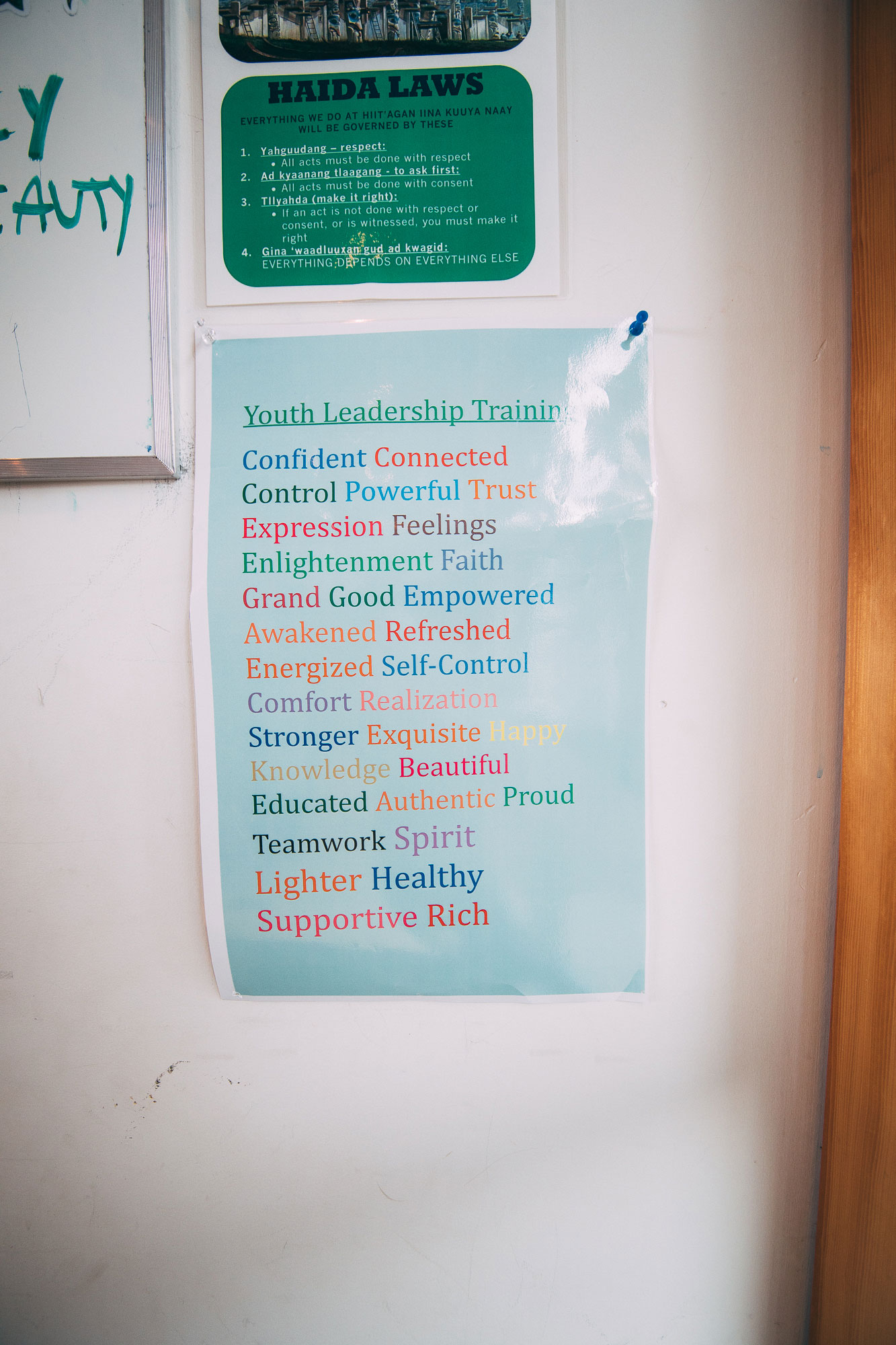

There were easily 30 kids in and out of the youth centre while I was there. They weren’t doing any traditional activities but I could see what he was talking about in the art on the walls and in the stacks of jars of salmon; I could hear it in the discussion of the upcoming Youth Assembly and the stories of the islands and ocean wildlife. I asked Willie what he would recommend to other communities seeking to uplift their youth.

“Be open to learning more than you’re going to teach the kids,” he answered, “because they’re always teaching some kind of lesson and it’s important to listen.”

“I’d say the most important thing to do is just to listen, to really truly listen to what the kids have to say so they feel like their voices are heard. Allow it to give a mirror to yourself so you can get an understanding of who you are too, and who you were as a kid. It creates a solid connection.”

I saw that connection firsthand. Willie greeted every person who walked through the youth centre doors by name. He laughed and joked and played music. He also knelt on the floor and talked quietly with kids who needed it.

With that image in my mind, I asked Willie if he thought about masculinity and emotional vulnerability in his work with the boys at the youth centre.

“I try to do a boys’ group on Fridays, to teach them all about that sort of thing. Teaching about that balance of how to express yourself, and still be a man even though you have emotions, even though you feel sad or weak or vulnerable. I definitely want to connect with the boys on that.” Willie talked about masculine and feminine energies, and teaching the boys balance in their lives and in their relationships. He also acknowledged gay, bisexual or transgender youth, which stood out to me because of the importance for LGBTQ youth to feel like they have an adult they can trust and a place they belong.

As for the boys, he said, “I try to be there for them as much as I can, and I find it’s harder to connect with them because they’re sort of raised in that way where they’re supposed to be very strong, they’re not supposed to show any emotions or that kind of thing. So I’m trying to find ways to connect with the boys and teach them those kinds of things.”

In having those strong relationships and emotional conversations, Willie saw himself as filling a void that he had experienced in his own childhood.

“When I was a kid growing up on Haida Gwaii, we didn’t have this kind of thing, we didn’t have any programs. And for myself, I was one of those kids that didn’t have anybody to talk to. I think it’s an important thing that kids get the opportunity and the chance to be able to express what’s going on inside of them so they don’t have to hang on to sadness or repress sadness, or just anything that’s happening. I’d like the kids to have a safe place where they can do that kind of thing with an adult that they can trust.”

He said he saw the youth centre as a place that mattered to young people, and that he wished he had had when he was growing up. “A personal goal of mine in being here is just to give the kids a safe spot, because there wasn’t much of that when I was a kid. We had to kind of hide out on the beach if we wanted safety from certain things.”

But his vision for the youth centre extended beyond the present moment. It began before even his own childhood with the traditional teachings and histories of the Haida Elders, and it stretched beyond the present to the young generation and the next. His vision for the youth centre was like the light of the rising sun before it crests the ocean horizon, touching lives that he couldn’t see.

“I’d like it to be a beacon for kids finding their own excellence, and their own selves and just reaching their full potential. Long-term goal is to create a generation that’s younger than I am, to make them better than my generation and have a better life. It’s always been the goal to be a precursor for the next generation so they can create a stronger, healthier legacy.”

It’s funny to hear the word ‘legacy’ when you’re in a space like that. You look around at the colourful handprints on the Haida art, at the hanging wetsuits still wet from the ocean, at the bike tracks outside the door and the list of child-written names signing in and out; and you feel it. You don’t feel a building that’s only been open for two years. You feel generations.

This is relatively unrelated but watch for Willie playing S’kwa in the first-ever Haida language feature film, Edge of the Knife, which is currently in post and should be out in the spring. Big community effort. Worth supporting.