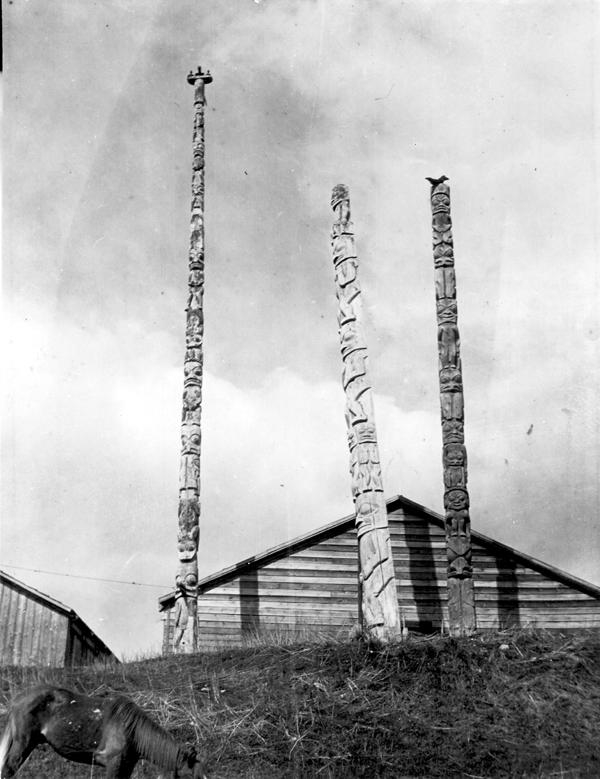

I stopped in Gitanyow on the Kitwanga River along the Stewart-Cassiar Highway. It was raining. The Gitanyow Historical Village and Band Council were closed because of a funeral, so I talked to a local and learned what I could. She told me about the traditions surrounding deaths in the village, the different clans in Gitanyow and among the Gitxsan people, and helped me correctly pronounce their local names (Gitanyow is pronounced GIT-in-yoh). I asked her how old the totem poles were. She looked at me steadily. “The totems have been here as long as we have.”

I went online and found that they’re described as ‘some of the oldest-known totem poles in the world.’

I also found out about the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs, the Wilp system, the Lax’yip, Ayookxw and Hla’ Am Wil. Rather than just being a historical site, Gitanyow is a place of great vision and unfolding agreements. I’ve spent some time reading about Gwelx ye’enst, the ‘exercise of Gitanyow’s rights and responsibilities to hold, protect and pass on the land in a sustainable manner from generation to generation.’ This is some of what I’ve learned.

Gitanyow culture is based on two Pdeek (Clans): the Lax Gibuu (Wolf) and the Lax Ganeda (Frog/Raven), which are each organized into four Wilp (Houses). Each Wilp has exclusive rights to its oral histories, crests and Lax’yip (territory), and is led by a Simogyet (Chief). The Chiefs make up the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs, who together address issues common across the Huwilp and uphold Gitanyow law. The law is the Ayookxw, a collection of traditions and values that have endured for thousands of years.

The Ayookxw were ignored and broken by White people throughout colonial history. According to the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs’ website, for example, Canadian governments have failed to recognize Gitanyow Huwilp title and rights by issuing approvals for resource extraction without having lawfully gaining the right to do so. This contravenes the Ayookxw because the Ayookxw carry the responsibility of the Gitanyow to “hold, protect and pass on the land and water of the territories in a sustainable manner from generation to generation.” This isn’t just a cultural practice. It‘s a legal obligation.

That means that the Gitanyow have resisted the violation of their rights and laws throughout the history of Canadian colonization. Writing in 2016, Libby Porter and Janice Berry described their resistance like this: “Achieving outside recognition of the Gitanyow Wilp system has been a longstanding struggle—one that dates back to the arrival of some of the earliest government surveyors and resource developers. Throughout this period, the Gitanyow have fiercely defended their territory and have long resisted government-imposed reserves. In the early twentieth century, European farmers attempting to settle in their territories were chased away, barricades were established on forestry access roads and Gitanyow Chiefs were jailed for confiscating government surveying equipment. Alongside these more direct acts of resistance, the Gitanyow Huwilp have long been laying the foundation for their own system of land-use planning—from the hand-drawn maps and ownership statements presented to Indian Agents as early as 1910 to the detailed fieldwork, inventorying and mapping that began in the late 1970s—and continue to do so to the present day.”

In 2005, the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs described the Huwilp as being heavily impacted by logging, and having limited capacity and no resources to meaningfully participate in consultation and accommodation processes. Many village sites, sacred sites and traditional resource gathering sites had been destroyed. The Gitanyow had no say on the development of their territories and no access to the wealth being generated in resource extraction.

That’s where the vision comes in.

“Through government-to-government agreements we are able to benefit from the resources from the Lax’yip without ever having to sacrifice any land, thus extinguishing the Gitanyow reliance on the Indian Act, ultimately creating a fully self-reliant system in which the Gitanyow are sustained through the resources on the land.” Glen Williams, Simogyet of the Maliii Clan and President of the Simgigyet’m Gitanyow

The Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs’ vision is a coexistence of Gitanyow and Crown title, sustainable land and resource use and the recognition of Gitanyow rights to economic benefits from their territories. This is currently being established through an Incremental Treaty Agreement in the form of the Gitanyow Lax’yip Land Use Plan, an interim step towards a final agreement still being negotiated. The underlying principles of the Gitanyow Lax’yip Land Use Plan honour Wilp authority, Lax’yip territorial rights and Hla’ Am Will. Hla’ Am Will refers to the ‘wealth of land, air and waters,’ and requires their protection to ensure the sustainability of the Gitanyow’s entire legal, cultural and economic system.

“The Gitanyow legal system,” reads the Hereditary Chiefs’ website, “does not reflect Western concepts of resource extraction for profit and unlimited consumption.” From what I can tell, that means this treaty agreement is begin written on their terms.

Treaties with First Nations in British Columbia differ from the rest of the country because they are being written now, in a context that differs greatly from earlier treaties in eastern and central Canada. The Rice Lake Treaty in 1818 was essentially viewed by the British as a land surrender. Treaty No. 6 in 1876 was signed in amidst the devastating effects of buffalo extirpation and smallpox epidemics. In contrast, the Gitanyow have a reputation as being both tough negotiators and having authentic collaborative relationships. This is the potential for something new.

In hindsight, I wonder if this is the norm of modern treaties being negotiated in British Columbia. Even if it is, it’s still worth sharing—particularly because if you look at the commemorative plaque from Canada’s centennial in 1967, all that was said about the Gitanyow culture was that it contained a “unique primitive art form.” That’s it.

Photos from Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs Photo Gallery. For more information about resistance to colonization in the BC Interior, check out Gitxsan History of Resistance.