In April 2017, the British Columbia government recognized 56 sites as historic Japanese-Canadian places and created an interactive map on Heritage BC to acknowledge all 176 nominated places across the province. That’s where I discovered that there was such a high Japanese Canadian population in Prince Rupert that it had a Japanese language school and segregated housing at the nearby North Pacific Cannery. I also discovered that I had cycled past the ghost town of Port Essington. I had never heard of it.

Port Essington was a cannery town on the estuary of the Skeena River. It was founded in 1871 by Robert Cunningham and Thomas Hankin and grew to become the largest settlement in the region; with trading posts, hotels, churches and a town hall supported by a dozen salmon canneries. The first Japanese Canadians to arrive were Shiga Aikawa and Yasukichi Yoshizawa in 1890. In the years following, Port Essington became the centre of a large Japanese-Canadian community involved in the fishing industry prior to World War II. By 1910, Japanese Canadians held three-quarters of nearly a thousand regional fishing licenses.

In 1942, all of them were forcibly removed.

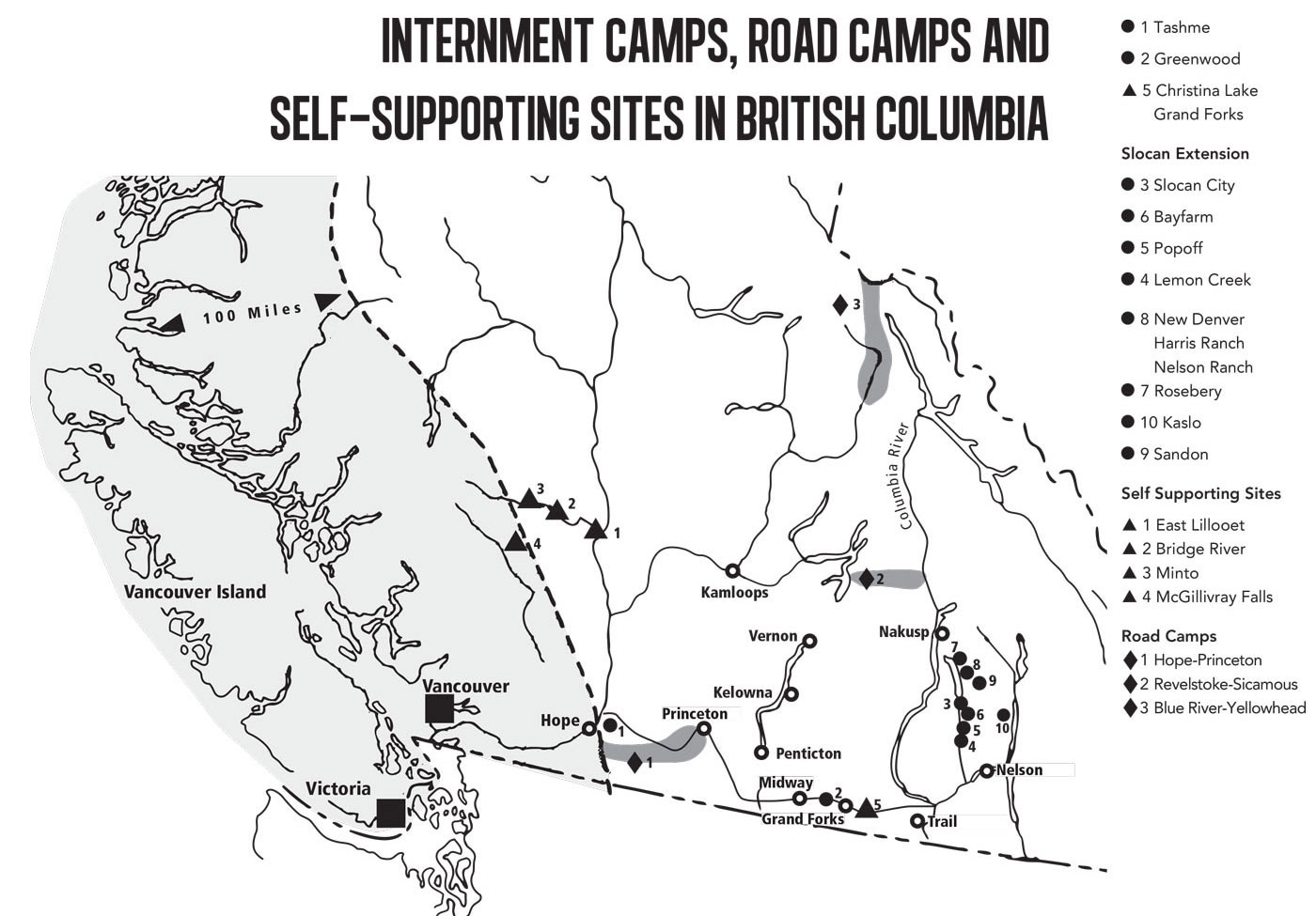

After the news of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour on December 7, 1941, decades of anti-Japanese fear and resentment erupted in British Columbia. Japanese Canadian industry workers were immediately fired. Japanese Canadian fishermen were ordered to stay in port and some 1,200 fishing boats were seized. Japanese language newspapers and schools were closed. In the following weeks, the unrelenting racism of federal Cabinet minister Ian Mackenzie and British Columbian popular opinion pushed the Canadian government towards a policy of forced relocation and internment. On January 16, 1942, the government designated the area 100 miles from the west coast as a ‘protected area.’ On February 7, every man of Japanese origin was forced to leave. Two weeks later, that expanded to include all persons ‘of the Japanese race.’

By the 1940s, Port Essington had declined significantly with the gradual closure of its canneries, but it still contained a large Japanese Canadian population. With the removal of the Japanese Canadians in April 1942, for example, enrolment at Port Essington Elementary School dropped from forty-five to thirteen. The families were boarded on a barge, taken across the Skeena and loaded onto a cargo train. They would never see their home again.

“It is the government’s plan to get these people out of BC as fast as possible. It is my personal intention, as long as I remain in public life, to see they never come back here. Let our slogan be for British Columbia: No Japs from the Rockies to the seas.” Ian Mackenzie, 1944

Throughout 1942 Japanese Canadians were taken with little warning to holding areas, such as the Hasting Park livestock building in Vancouver, where they were held sometimes for months before being transported away from the coast. Some families were separated, with fathers being sent to road camps or prisoner-of-war camps in Ontario. Other families were sent to Manitoba and Alberta to work as farm labour. Many were housed in hastily erected internment camps in the BC Interior, where they suffered unimaginable struggles through the long winters of the war.

“The walls of our shack [in Lemon Creek],” recalled Yukiharu Misuyabu, “were one layer of thin wooden board covered with two-ply paper sandwiching a flimsy layer of tar. There was no ceiling below the roof. In the winter, moisture condensed on the inside of the cold walls and turned to ice.”

In 1943 the Canadian government granted the Custodian of Enemy Property permission to sell all properties belonging to Japanese Canadians, who had been forced to leave their homes behind. They were sold at a pittance, leaving thousands of Japanese Canadians bankrupt and financially insecure. The Canadian government hoped that liquidating Japanese Canadians’ possessions in British Columbia would discourage them from returning to the province, taking a step towards its program of post-war dispersal. Japanese Canadians were then given the choice between immigrating back to Japan, or resettling east of the Rockies. It wasn’t until 1949 that the restrictions of the War Measures Act on Japanese Canadians were lifted.

When the Japanese Canadians of Port Essington were allowed to return to the coast, they found that in their absence its population had plummeted and the village had burnt to the ground.

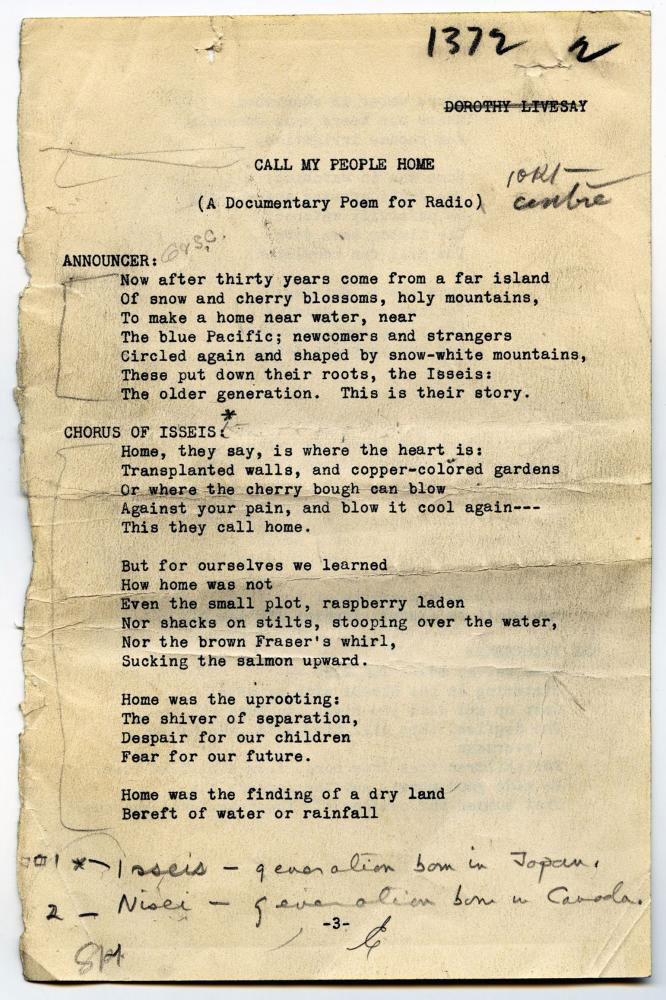

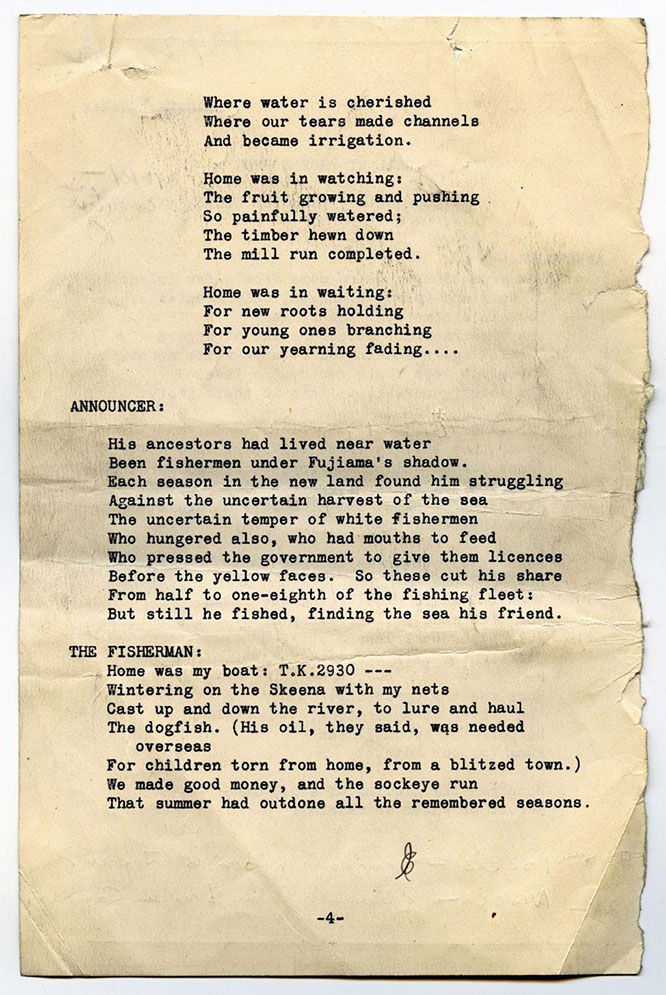

“Home, they say, is where the heart is:

Transplanted walls, and copper-colored gardens

Or where the cherry bough can blow[…]

But for ourselves we learned

How home was not

Even the small plot, raspberry laden

Nor shacks on stilts, stooping over the water,

Nor the brown Fraser’s whirl,

Sucking the salmon upward.Home was the uprooting:

Dorothy Livesay, Call My People Home

The shiver of separation,

Despair for our children

Fear for our future.”

“Our history is made up of people. People who welcomed strangers to their land. People who bravely left their home and families for new opportunities. People who left on these waters to reach the foot of the Rockies—who saw unlimited possibilities in this land. Their actions make our history. Some of it is good. Some is not. But it is all important—it is why we are who we are. And our young people need to know about this. Without understanding where we have been, there is a good chance we will repeat mistakes of the past. Learning about our history helps guide us in the future.” — Governor General Romeo Le Blanc, 1999

I’ll conclude with a link to an article published in the Nikkei Voice in 2016: Japanese Canadian Internment in Relation to Syrian Refugee Crisis. We know what Canada has been. We know that because Port Essington burned. What, then, will we become?

Images from the University of British Columbia Library, Library and Archives Canada and the Japanese Canadian Hastings Park Commemoration and Education Project. You can learn more about the history of Japanese Canadians at Hasting Park at Hasting Park 1942. I also came across a film on the National Film Board called Minoru: Memory of Exile, a great way for children to learn more about the history of Japanese Canadian internment.