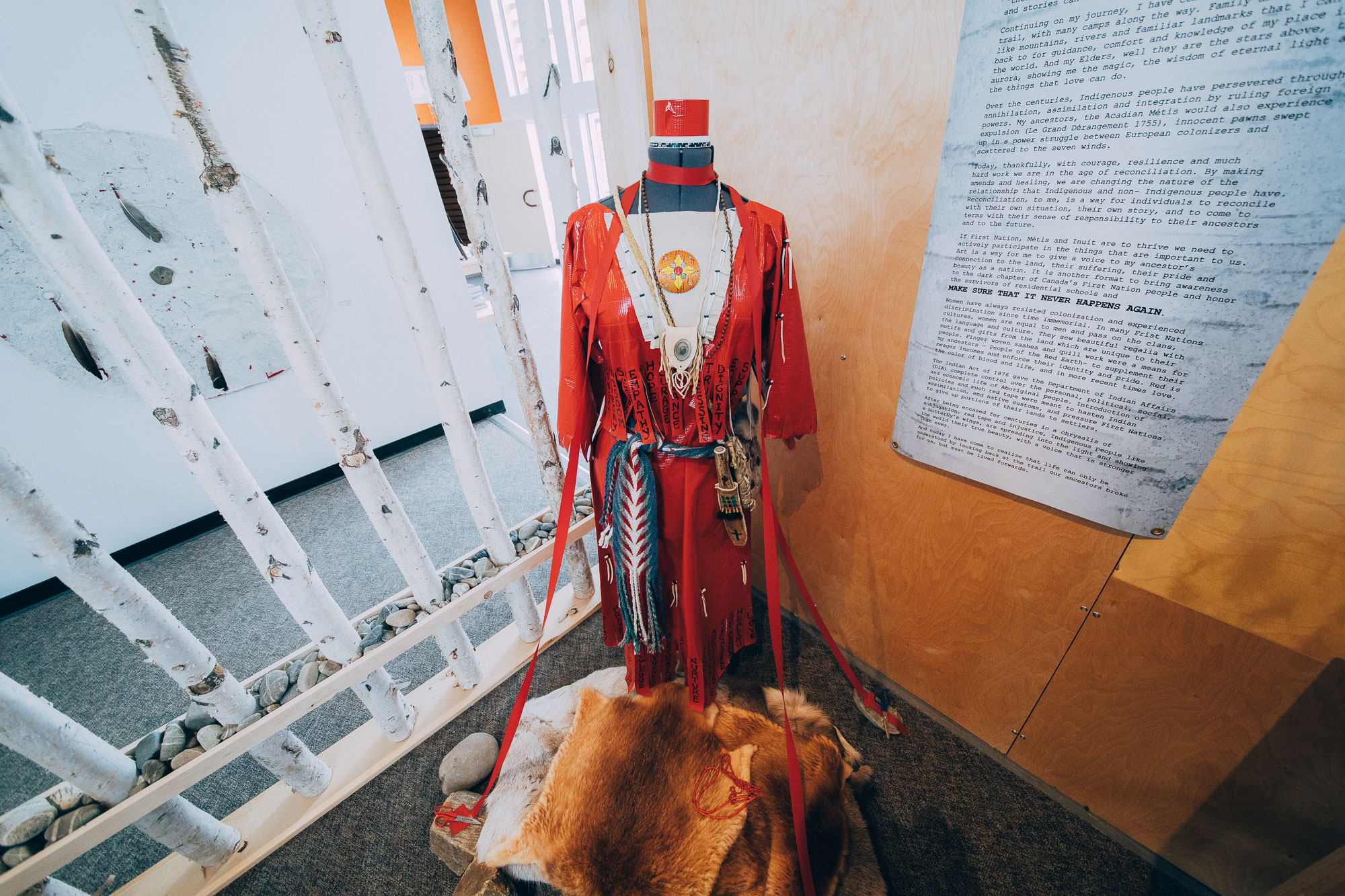

Asia was working at the Dänojà Zho Cultural Centre in Dawson City; a museum, cultural centre, gallery and gathering place for Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in people and culture. The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in are one of eleven out of fourteen Yukon First Nations who have settled land claims with the Canadian government and become self-governing. The cultural centre was a testament to their careful work maintaining and reclaiming traditions and cultural practices. They had oral-based histories and stories from long ago, and information about their land claim and descriptions of continuing work supporting youth education. They had a space dedicated to truth and reconciliation centred on local Elders’ stories of residential schooling, which had only just recently been shared and compiled into a scrapbook.

“Through destruction and adversity, from the ashes grows the fireweed, the most vibrant bloom of the Yukon,” read a quote from Fran Morberg-Green on one of the displays in the residential schooling space. “Colonization was that scorching and now we must be like the fireweed, who grows strong roots, who replenishes and who stops the erosion.”

Asia was like the fireweed.

She was in high school; this was her summer job. She was Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in and proud of it. You could tell because throughout her tour in the cultural centre she shared stories of her family members. Her great-grandfather showed Royal Northwest Mounted Police constables the traditional hunting route that became the Dempster Highway. Her grandfather signed the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Final Agreement with the Canadian government. The land claim was history, for Asia, but it was also inherently part of her present. If her grandfather had not been part of establishing self-governance for Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation, then, under the Indian Act, she would not have First Nation status. It wouldn’t matter what stories she could tell or what family she belonged to on her mother’s side. She wouldn’t be legally Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in. That would be a loss—and it’s a loss that is still happening all across Canada.

But not in Dawson City. Instead, Asia spoke with vision and hope about her future and the future of her community. I asked her where she thought that hope came from and one of the things she spoke about was education, and seeing her culture and the history of residential schooling present in her classrooms.

“Right now we’re working on integrating First Nations history, what’s happened to us around Canada and locally here in Dawson, into our school system,” she said. “Hopefully by doing that more minds would be opened. Minds opened so that perspectives can change; and we would be able to live in harmony with each other, First Nations and not. And maybe inspire other First Nations in Canada to do something similar, just because of all the rough conditions and stuff in Ontario and Manitoba, it would be nice to try to create a better situation, a better lifestyle, a better…”

She wasn’t sure, for a few moments, what noun to add to finish the sentence. Then she returned, with a smile, to the question I had asked.

“A better hope for the future.”

“What I hope to see is more peace and harmony, living together, no racism. Or minimum racism, minimum judgement. Because there’s always going to be racism and judgement.”

In other places in this journey, cities like Thunder Bay and Winnipeg and smaller communities in northern Ontario, it sort of seemed like proximity to Indigenous communities was in part what led to anti-Indigenous racism. I had a feeling of uncertainty in those places. How do I support right relations when the confluences of Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures seem to be the most polarized and most racist places in Canada? How do I know if racism is the rule rather than the exception? What does reconciliation look like then?

So it was significant to me to hear that in Asia’s experience, Dawson City wasn’t like that.

“Going to cities, like going to other places in Canada,” she said, ”I see racism. Here, I’ve never experienced racism. Sure, there’s always that joking comment but it’s like whatever. But I’ve never really experienced real racism here, or real racism until I went to other parts of Canada, and then I could just see by looks I was given or comments that were made that it’s real. It still happens today. Even though I was lucky enough to grow up here, where there is very little of it that I’ve experienced.”

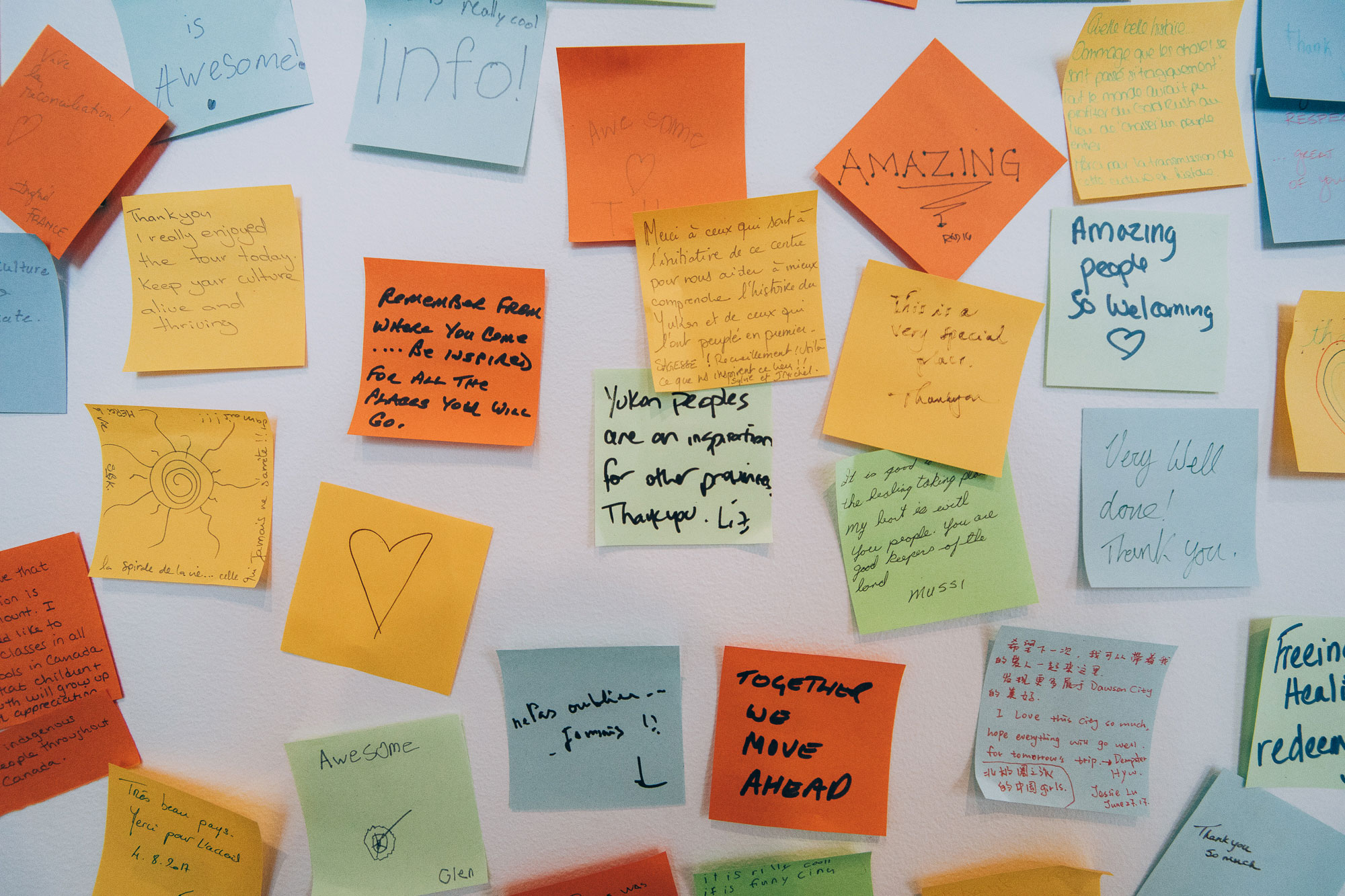

I don’t know if I can express the power of a high-school-aged girl talking unhesitatingly about her Indigenous culture, describing a childhood free of racism. I’ve met grown men on this journey whose eyes would fill with tears at the thought. Instead I’ll describe this image, an entire wall of sticky-note messages left by visitors of the cultural centre. They echoed like hundreds of voices sharing pride and encouragement. “An inspiration,” they said. “Keep moving forward.” “My heart is with you.”

“Mussi cho,” they said. “Thank you.”

Asia knew racism. She knew assimilation and degradation and colonialism. Of course she did, she worked with those stories every day in the space of the cultural centre dedicated to residential schooling. But that wasn’t the end of their history, and Asia knew that too. It was like the messages on the wall had been written for her. She was a new generation. Connected. Unbroken.

Fireweed.