On May 1, 1919, building trade unions employed by the Winnipeg Builders Exchange were faced with an ultimatum related to their wages and decided to go on strike. The following day, the city’s metal trade workers walked off the job after the metal shop owners refused to negotiate with the unions. A week later, the unionized workers of the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council voted 11,000 to 500 in favour of a general strike.

A general strike is a strike that encompasses a substantial portion of the total labour force in a city. Its purpose is solidarity with the workers advocating for themselves, using the weight of the united working class to increase the stakes of the strike.

The general strike in Winnipeg was set to start at 11 AM on May 15. By noon, the city was at a standstill. Ninety-four unions were on strike, and in the end nearly 30,000 people walked out on their jobs. The Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council established a Central Strike Committee to direct the strike and determine which services to maintain within the city. The strike was positioned as a fight for better wages and reformed working conditions, as well as a demonstration of the entire principle of union-based collective bargaining.

“The almost unanimous response by working men and women closed the city’s factories, crippled Winnipeg’s retail trade and stopped trains. Public-sector employees, including policemen, firemen, postal workers, telephone operators and employees of waterworks and other utilities, joined the workers of private industry in an impressive display of solidarity.” J. Nolan Reilly, Winnipeg General Strike

Winnipeg’s elite, including manufacturers, bankers and politicians, formed the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, whose purpose was to break the strike. Ultimately, the connections of the Citizens’ Committee to the halls of power in Ottawa led to the dismissal of federal workers in Winnipeg, the amendment of the Immigration Act and Criminal Code, arrest of leaders of the Central Strike Committee, and a violent reprisal from the Royal North-West Mounted Police that left 30 casualties. Facing the combined forces of the government and the Citizens’ Committee, the strike was defeated on June 25.

What struck me about the Winnipeg General Strike was the language used by the Citizens’ Committee against the strikers. Having lost the majority of their workers, The Winnipeg Free Press and Winnipeg Tribune turned against the strike. The Citizens’ Committee made use of the language of the First World War and Russian Revolution in the press, calling the strikers ‘bohunks’ and ‘anarchists’ and ‘alien scum.’ The New York Times printed the headline ‘Bolshevism Invades Canada’ on its front page. Solicitor General and future Prime Minister Arthur Meighen declared, “The leaders of the general strike are all revolutionists of varying degrees and types, from crazy idealists to ordinary thieves.”

There’s historically no truth to that. But at the time, widespread fears of revolutionary conspiracy meant that there were no efforts made towards conciliation or negotiation with the strikers. The strike became antagonistic. Black and white.

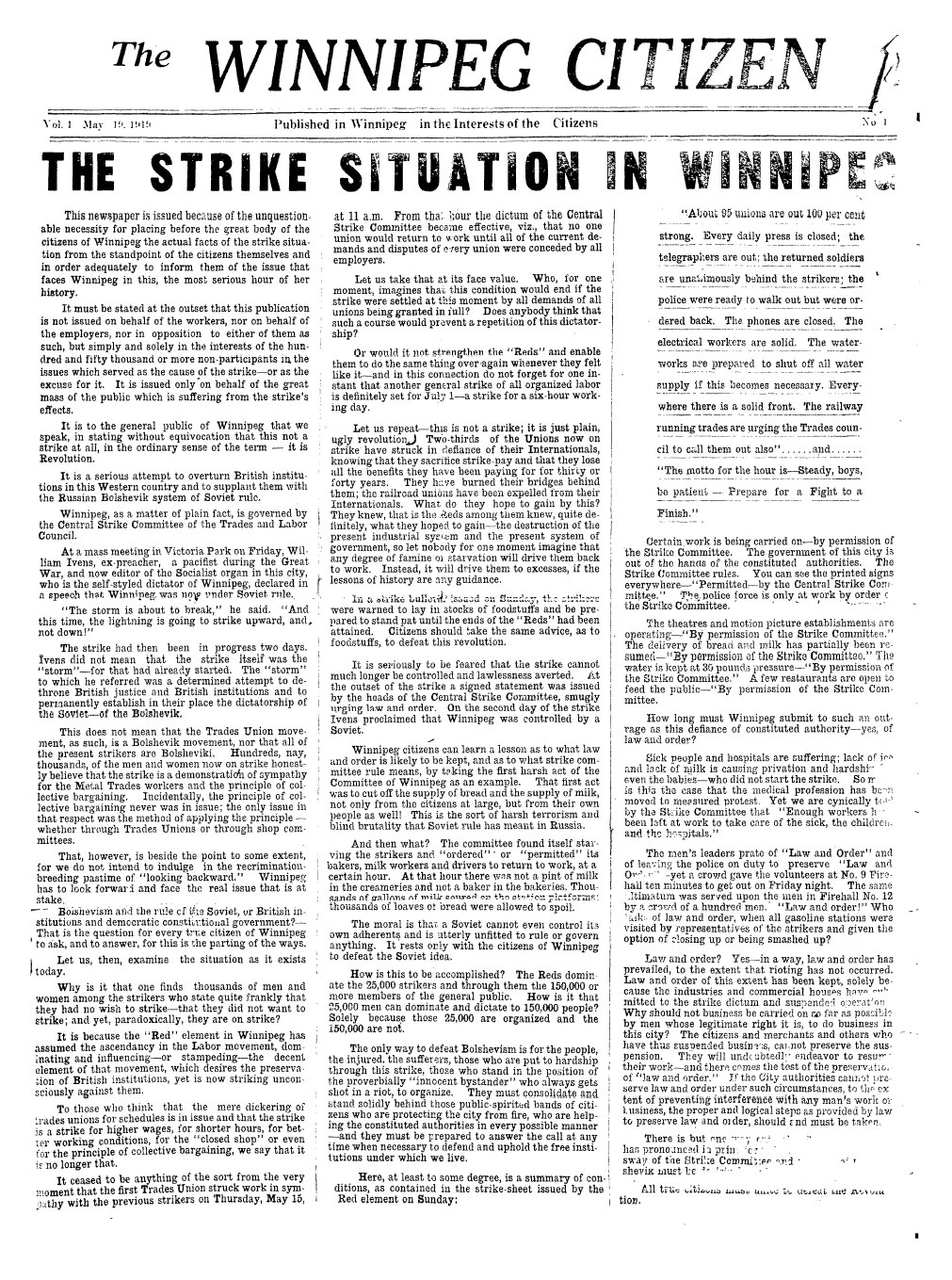

“This is not a strike at all,” declared The Winnipeg Citizen on May 19. “It is Revolution. It is a serious attempt to overturn British institutions in this Western country and to supplant them with the Russian Bolshevik system of Soviet rule.”

There are a lot of ways that the history of the Winnipeg General Strike continued after 1919, for example with the defeat of the federal Conservative government in 1921 or the establishment of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation in 1932 that became the New Democratic Party in 1961. A wave of increased unionism and militancy swept across Canada in the wake of the Winnipeg strike, yet almost three decades passed before Canadian workers secured union recognition and collective bargaining rights.

“History is valuable. When we choose to remember it, history positively informs our present and future. […] Although we can remember the strike in 1919 as history long past, we can see its impact on today. Moving ahead, we can use its lessons as an impetus to address the ongoing issue of social inclusion.” Kate Kehler, General strike lessons learned

Along with histories and lessons associated with the Winnipeg General Strike and the labour movement in general, we should recognize what it means to villify our opponents. The Citizens’ Committee chose to paint the entire labour movement with the same brush. In Winnipeg in 1919, if you were advocating for your rights or the rights of your fellow workers, you were a revolutionary extremist. You had to lose.

That’s what propaganda, biased media and shallow politics do. They create division and they turn us against each other. They prevent cooperation and they make winners and losers.

Surely we can do better.

Photos from Winnipeg Free Press Archives and the Manitoba Library Consortium.