Neys Provincial Park is a park on the north shore of Lake Superior, known for its sand beaches, unique plant species and islands made famous by the Group of Seven. Its natural dune ecosystem, however, was almost entirely flattened and developed in the 1940s for the construction of a wartime prisoner-of-war camp. The landscape of Neys, then, has a history far more complex than the natural history of most provincial parks.

I had a pamphlet from the park about Neys’ history during World War II but I lost it somewhere, so bear in mind my research is missing the easiest and perhaps most comprehensive source.

German imprisonment

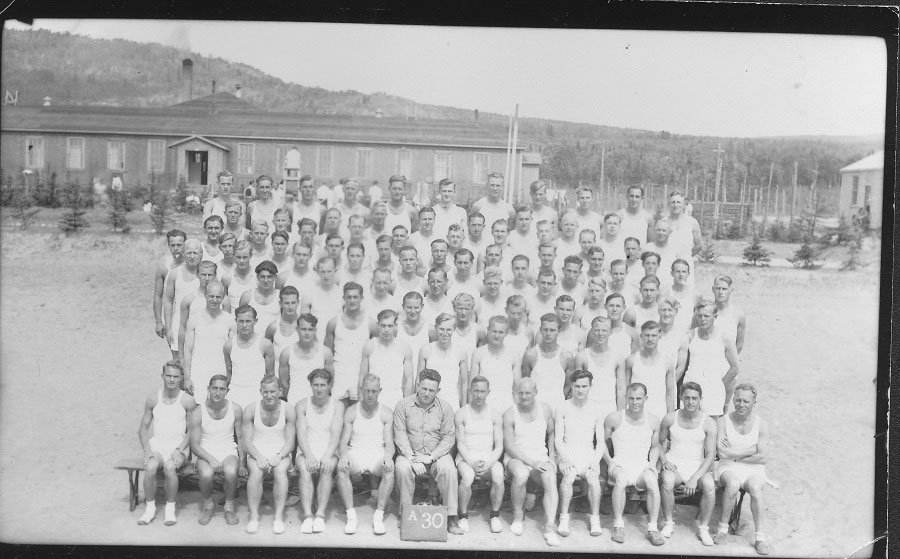

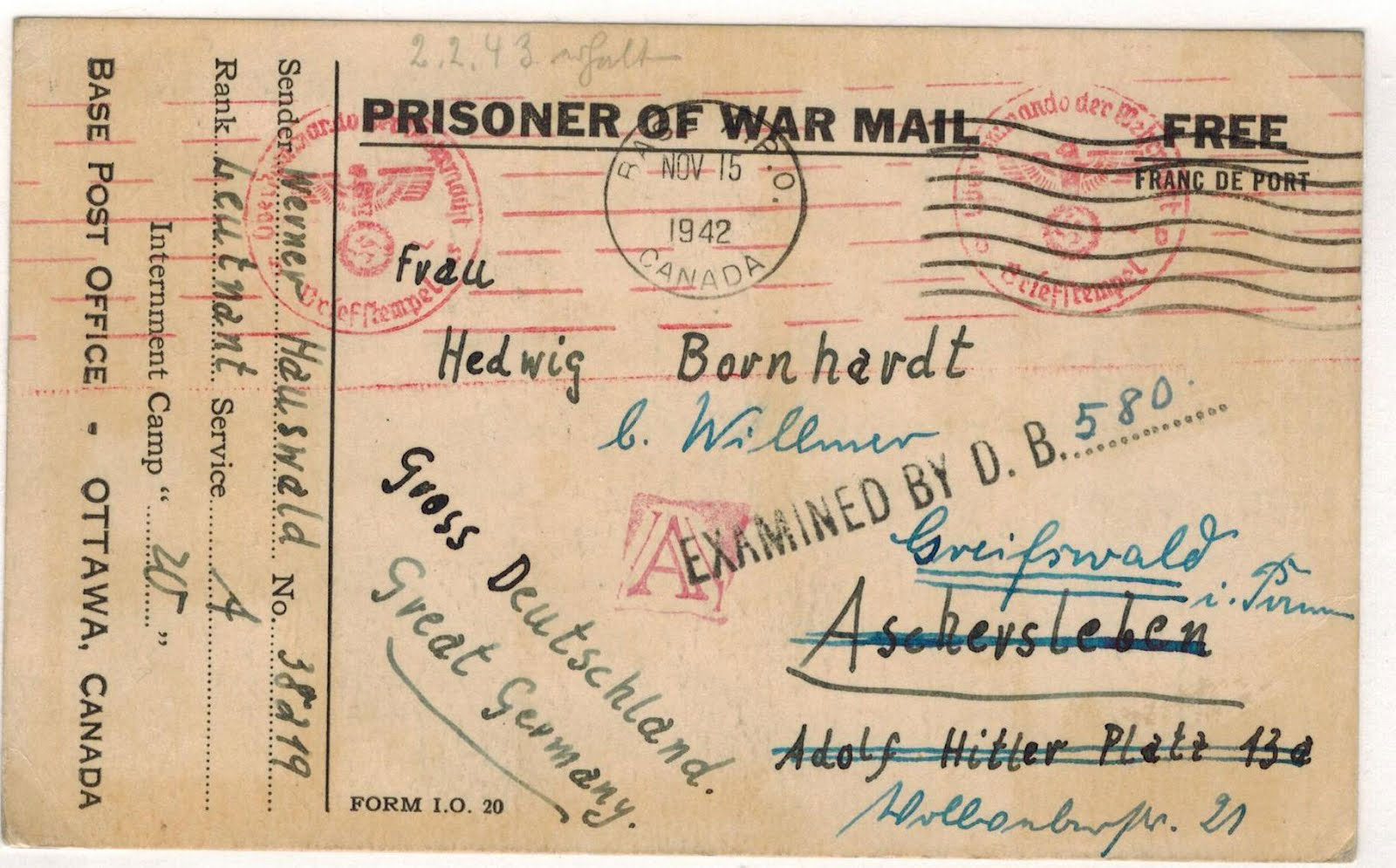

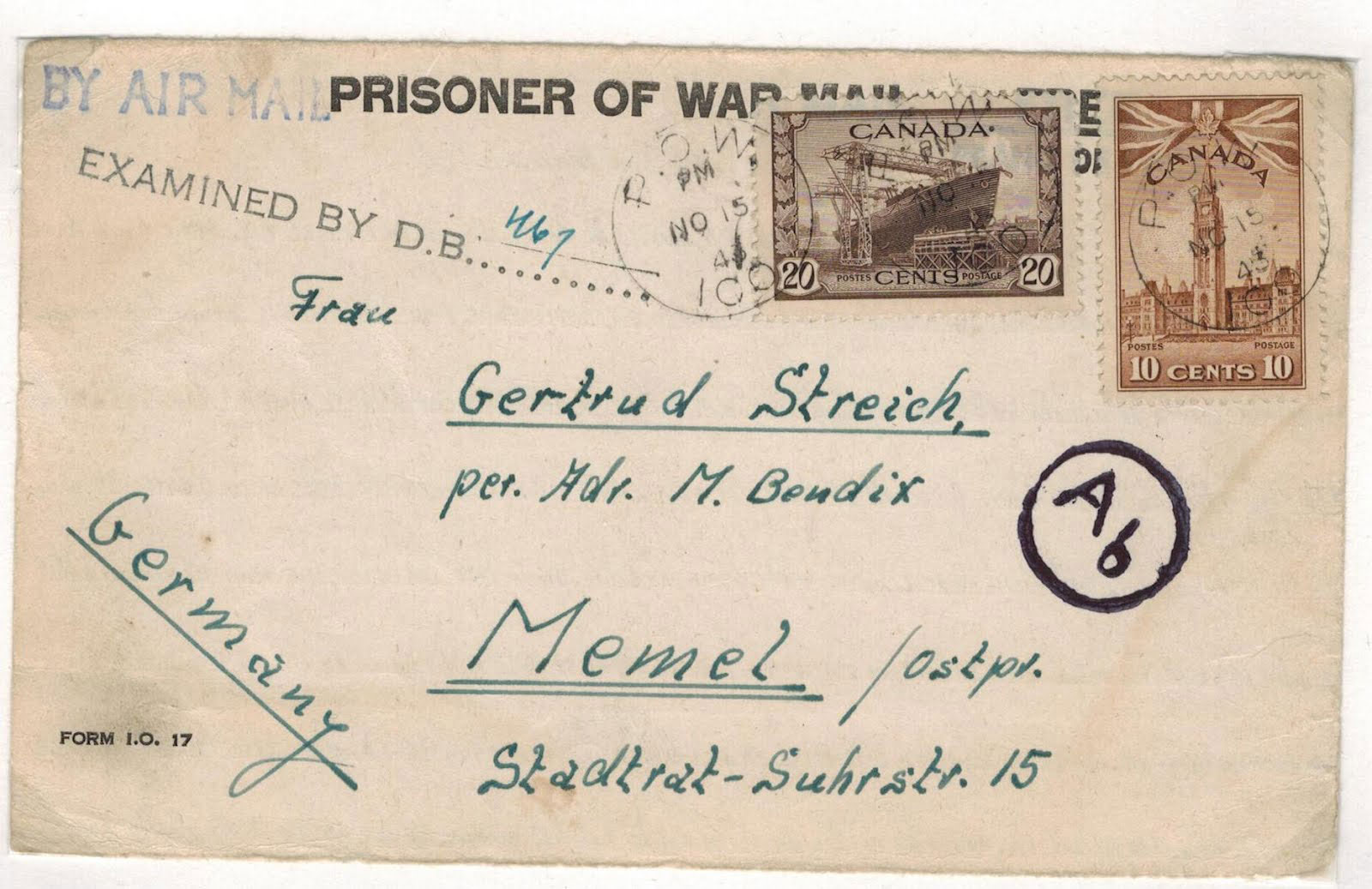

Canada was a useful place for the Allies to imprison German soldiers because Britain had limited space for containing prisoners and the Atlantic Ocean effectively kept them far from the theatres of war. So Neys Camp 100 (temporarily called Camp W) was built in 1941 along with three other POW camps on the coast of Lake Superior and 24 other camps across the country. Throughout the war 34,000 German prisoners of war were interned in Canada.

Neys Camp 100 had the capacity to hold 500 prisoners and 100 guards, with 27 buildings of various sizes in a rectangular compound surrounded by three rows of 10-feet-high barbed wire and a guard tower in each corner.

German prisoners at Neys were put to work logging in the Pic and Little Pic River valleys. It was hard labour, but the guards were held to a strict honour code that prohibited the use of unnecessary force against the prisoners. It’s a point of pride among many Canadian historians and writers that Canada was internationally recognized for its humane treatment of prisoners of war. The anecdote I saw frequently was the number of German soldiers who had been imprisoned in Canada and then immigrated here after the war.

I don’t remember the exact timing of Neys’ reorganization, but if I remember correctly it followed a large escape at Angler POW camp east of Neys in April 1941. At some point in researching this I read something that compared Angler to the Great Escape from German-held Stalag Luft III—the same kind of large-scale escape operation, but instead of Allied airmen in Germany, it was German soldiers in Canada. So after the large and well-publicised the escape attempt in Angler (in which all the prisoners were eventually killed or recaptured) there was a reorganization of the POW camps on Lake Superior. They implemented a classification system of the German prisoners: ‘Whites’ were soldiers who had never supported or who had become disenchanted with Nazism, ‘Greys’ were neutral and ‘Blacks’ were political and ideological Nazis. Neys became a prison primarily containing Black-designated soldiers.

If you walk through any of Neys’ forests, you will find remnants of imprisonment nestled among the quiet pines. Pieces of concrete jut out from the ground, half-hidden below soft moss. Scraps of metal collect pine needles, creating small beds of soil where flowers grow.

Maybe it was the sunset, or the lack of wind. Maybe it was the feeling of cold wire-wrapped nails between my fingers with the smell of pine around me. Whatever it was, the ruins of Neys had a stillness to them. They lingered as a witness to the past, but felt almost forgotten as they gradually vanished beneath the slow growth of the forest.

That is the risk of history, I suppose. Our world changes and like trees we inexorably look forward, forgetting where our roots are planted in order to reach for the sky. Sometimes, however, we need to look at where we started in order to look ahead with more clarity.

Neys wasn’t just a POW camp. I read some sources that called it a Japanese internment and/or work camp, but as best as I can tell it was used in 1946-1947 as a relocation camp for Japanese Canadians who had been displaced and held in internment camps during the war. Angler, however, was a site of Japanese internment.

Japanese internment

Even if Neys was just a relocation camp, I couldn’t figure out what interned Japanese Canadians were doing in Ontario—I thought that history was more or less confined to British Columbia. So I looked up the history of Japanese internment in Canada in The Canadian Encyclopedia, and I learned a lot.

First of all, I discovered that WWII Japanese internment had its roots in anti-Asian discrimination in Canada as early as the late 19th century. In 1907, for example, White Canadians led a riot through Chinese and Japanese neighbourhoods, breaking windows and assaulting residents.

At the outbreak of war in 1939, Nisei (Canadian-born citizens of Japanese ancestry) were excluded from conscription, partly in order to prevent Japanese Canadian suffrage. After the bombing of Pearl Harbour, long-held anti-Japanese hostility erupted with White farmers, merchants and political leaders accusing Japanese Canadians of being in collusion with Tokyo despite the heads of the Canadian Army and Navy vigourously denying that there was any serious danger posed by Japanese Canadians.

“Major General Maurice Pope, vice-chief of the General Staff, was disgusted when a Pacific Coast politician told him privately that his constituents considered war with Japan a heaven-sent excuse to eliminate Japanese Canadian economic competition.” Greg Robinson, Internment of Japanese Canadians

Political pressure from British Columbia ultimately led Prime Minister Mackenzie King to order the removal of all adult Japanese men from the west coast.

This is what brings the history of Japanese internment to the shores of Lake Superior. The brutality of the mid-winter expulsion of 22,000 Japanese Canadians from their homes led a group of Nisei to form the Nisei Mass Evacuation Group, which risked arrest to get the government to allow families to be relocated together. The most militant of these Nisei were flagged as troublemakers and sent to POW camps in Ontario.

There’s more history to Japanese internment, the confiscation of property, the hard labour of work camps, the lack of food, clothing and education, and the forced resettlement of Japanese Canadians east of the Rocky Mountains or repatriation to Japan; but my goal was to connect the Neys and Angler POW camps to the history of Japanese internment. Here we are.

In seeking to learn from the past, I feel like wartime offers a more uncertain set of lessons. Everything has to be put in the context of total war, and a lot can be justified with the War Measures Act. The imprisonment of German soldiers doesn’t seem particularly related to Canadian culture today. The internment of Japanese Canadians—who even at the time were not considered a threat by the Canadian military—is perhaps more relevant.

If I talk about political decisions motivated by anti-ethnic sentiments, about popular fears of economic destabilization because of newcomer populations, about controlled immigration and forced deportation, am I talking about 1941 or 2017? It’s hard to tell. Are there similarities between anti-Asian discrimination in the 20th century and Islamophobia? I would argue there are. Have we learned any lesson from the oppression of an entire group of people who history has shown posed no threat to Canadian security whatsoever? I would argue we haven’t.

It’s not just me. Individual Japanese Americans who were imprisoned in WWII have spoken out in defence of Muslims. The National Association of Japanese Canadians published a statement denouncing the rise of racism and Islamophobia following the election of Trump last December. “The attacks provoke a chilling déjà vu for those of Japanese descent in the USA and Canada,” they wrote. “Just as Japanese Canadians and Japanese Americans were targeted in the 1940s and smeared with the ‘enemy alien’ label, we see Muslims being targeted today.”

“Fear and discrimination must not determine our policies or our actions. We, as citizens, must take every opportunity to speak up and act to protect our rights and freedoms. […] The voices to challenge the government’s attack on its own citizens in the 1940s were missing. We have an opportunity to join a loud chorus of voices to reject the current calls for hatred and division. We will stand together to face the uncertainty and ensure that the historical injustice our families endured is not repeated.”

The history of Neys is partly forgotten beneath moss and lichen in the Lake Superior pine plantation, but it is also partly alive and fighting with every inch of its strength against today’s Islamophobia that so closely mirrors the attacks on Japanese Canadians and Americans of the Second World War. We would do well to heed this call to action. The internment of Japanese Canadians is seen as a black mark on Canada’s history. Let us not repeat it.

Photos from Nipigon Museum and Postal History Corner. For more information about German POWs in Canada you can watch the documentary The Enemy Within on the NFB. For an account of the Japanese relocation experience you can watch Ayo Hagashi in the CBC Archives.