I recently researched and wrote a piece about the Québec sovereignty movement after coming across a colourful mural along the highway southwest of Percé. But what about when there isn’t a aesthetic catalyst to take out the camera and audio recorder? What about just an isolated town that’s seen better days?

Such was my experience in Murdochville. The town seemed pretty deserted and a bit run-down, and apart from a centre-ville hotel with an unexpectedly large dining hall and a stillness that felt somehow nostalgic, there wasn’t a lot to note. It wasn’t until afterwards that I found out that Murdochville was the site of one of the most important strikes in Québec history.

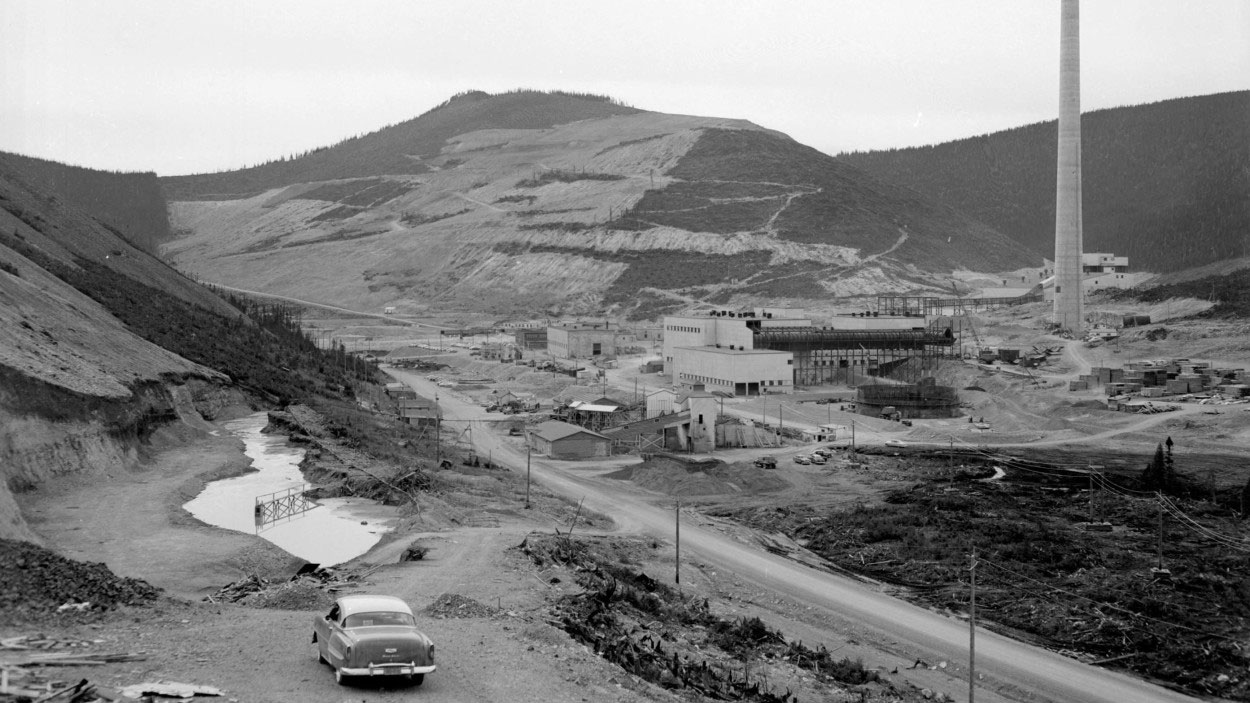

Murdochville was incorporated in 1953 after the discovery of copper ore and arrival of Noranda Mines. It was a company town, and its peak population of about 4,000 in the 1970s depended entirely on the mining industry. The rise and fall of Murdochville is its own significant story; from a stable, prosperous economy that was the envy of eastern Québec to the mass unemployment and steady decline that followed the mine’s inevitable closure. Konrad Yakabuski’s 2004 article in The Globe and Mail, Death of a Company Town, is worth reading in that respect.

I will endeavour, however, to focus on the mine workers’ strike, and that means returning to the 1950s.

The opening of the mine brought in hundreds of workers, who formed a union in 1954. The union, still unrecognized by Noranda, allied with the United Steelworkers of America to avoid being quashed, and in March 1957 after the forced dismissal of their president, Théo Gagné, they voted to strike. The strike was painted as an illegal direct action for higher wages and better work conditions, but it was more than that. It was a battle for recognition.

Pierre Elliot Trudeau, still at that point just a Montréal lawyer, travelled in solidarity to Murdochville and stated, “This is a fight for recognition, this isn’t a fight for certain advantages. And I think trade-union people throughout the province should lay down their tools and show their economic force.” Noranda, known for their anti-union position and supported in that position by the Duplessis provincial government, responded to that potential force by seeking to end the strike through any means necessary.

The provincial government deployed 80 police officers to Murdochville, while Noranda hired 40 agents de sécurité from the Atlas Detective Agency. These armed goons targeted the strikers while Noranda hired hundreds of strikebreakers, or scabs, to undermine the walkout. Clashes between the strikers and law enforcement were frequent.

“I saw a worker chased by the company’s enforcers die of a heart attack, a Noranda bulldozer demolish the picket line and the union office completely ransacked,” recalled Lawrence McBrearty, who was 13 years old during the strike and later became a union leader. “In 1957, the police of Duplessis walked around with machine gunes and left the Noranda agents to intimidate the workers as they wished.”

“We were scared, certainly. We wondered where we were.”

In August, hundreds of protestors marched in Murdochville to support the strikers, including Jean Marchand, Michel Chartrand, Pierre Elliot Trudeau and Réné Lévesque. In September, a protest of over 5,000 people demonstrated outside of the provincial government in Québec City. By early October, however, the strike was defeated.

The mine workers lost everything. Noranda kept the scabs and only rehired 200 strikers, who had to accept significant wage cuts. The rest faced unemployment and struggling families. The union, moreover, was sued by Noranda’s subsidiary and within a decade was condemned to pay Gaspé Copper Mines $1.5 million. The story reads like the aftermath of the 1892 Homestead Strike in Pennsylvania or the 1984-85 miners’ strike in the United Kingdom. They went back to work. Reality hit hard.

The legacy of the Murdochville strike, however, continued far beyond 1957. The determined miners of the inland Gaspésie shifted the discourse, creating a turning point in the struggle for workers’ rights. “After the strike,” explained Michel Saint-Pierre, a member of the union organizing committee at the time, “the right to negotiate was authorized, labour standards boards were created, a new labour code was adopted in Québec.”

In describing the strike earlier this year, Claudia Feuvrier wrote, “Murdochville symbolizes the forefront of the uprising of the entire population. Murdochville, it is the moment that workers become aware of their rights, on one hand, but above all of their capacity for large-scale mobilization.” Her words are echoed by Gaspésian historian Jean-Marie Thibeault, who wrote that the role of Gaspésie is too often obscured.

“If we [in the Gaspésie] are not an ignorant people, we are an ignored people. Few people know, but Québec owes much to the Gaspé workers, to the strikers of the Gaspé Copper Mines. The company and the government defeated the reds, but after Murdochville, there will no longer be the same working conditions in Québec. The bosses and government authorities will understand that workers are also humans and must be dealt with as such. In 1960, we will speak of the Quiet Revolution. Had it not been for the Murdochville strike, we might have spoken of the Bloody Revolution.”

“The Quiet Revolution,” he concludes, “began in Murdochville.”

This year marks 60 years since the Murdochville strike, and the fact that we passed through the bloody streets of 1967 without stopping except for a coffee at the unexpectedly large hotel shows how elusive history can be. It is up to all of us to learn these stories in any way that we can, in order to keep the legacy of those who fought for our rights alive.

Photos from Metallos, Radio-Canada and Musée de la Gaspésie.