I originally stopped because the logo of the Mi’gmaq Maliseet Aboriginal Fisheries Management Association (MMAFMA), on a signboard beside the highway, was so intriguing. It featured a modern fishing boat flanked by two breaking waves, with two beaded feathers bordering it to the left. It wasn’t predictable. It made me wonder what exactly it stood for, and with a sole car in the gravel parking lot, I decided to knock on the door.

I didn’t end up learning much about the MMAFMA, but I did learn a lot about Salaweg, one of the organization’s initiatives. The sole car belonged to Sandra, who was spearheading the Salaweg project and had spent the morning on a fishing boat harvesting.

Harvesting algae.

I’ve talked a couple times about the feeling of learning something I didn’t know that I didn’t know, and this was one of those times. I pulled out my phone to record some audio and listened hard. The audio is in French, by the way, but I’ll translate most of it in the text.

“This morning I left at 4:30 AM from here to Paspébiac, where we gathered about 200-300 kilograms of kelp.”

I mentioned to her later that she seemed very energetic for having worked hard at harvesting and cleaning the kelp since before sunrise. “C’est la mer,” she said. “It’s the ocean.” She described her younger life close to the west coast of France.

“I remember being three years old and asking my dad to take me to watch the ships on the coast. Even then I wanted nothing more than to be a fisherman.”

The idea to cultivate laminaire sucrée began with an inventory of wild biomass in the Baie des Chaleurs on the south coast of the Gaspésie. The bay was known to have a high density of wild kelp. In French, Sandra described it as champs d’algues, which literally means ‘fields of seaweed.’ It wasn’t until I started to transcribe the audio that I realized that algues referred to massive kelp forests. I thought kelp forests only grew in the Pacific.

Gesgapegiag First Nation was originally interested in sustainably harvesting the wild kelp, but they knew that these kelp forests were very important for the ocean ecosystem. Sandra gave the example of kelp providing a pouponnière, a nursery, for baby fish. They didn’t want to disrupt ocean life because a large part of the coastal fishing industry is based on wild lobster.

“We are very involved with the Gesgapegiag and Gespeg communities and the lobster fishery, who felt something a bit contradictory. They wanted to take advantage of the biomass of kelp but at the same time, it's difficult to manage a wild stock when you don't know how it will respond.”

Instead of harvesting the wild kelp, they decided to grow it independently. “We’re just starting,” she said. “This is the first year that we’ve had a crop of kelp to be made into food.

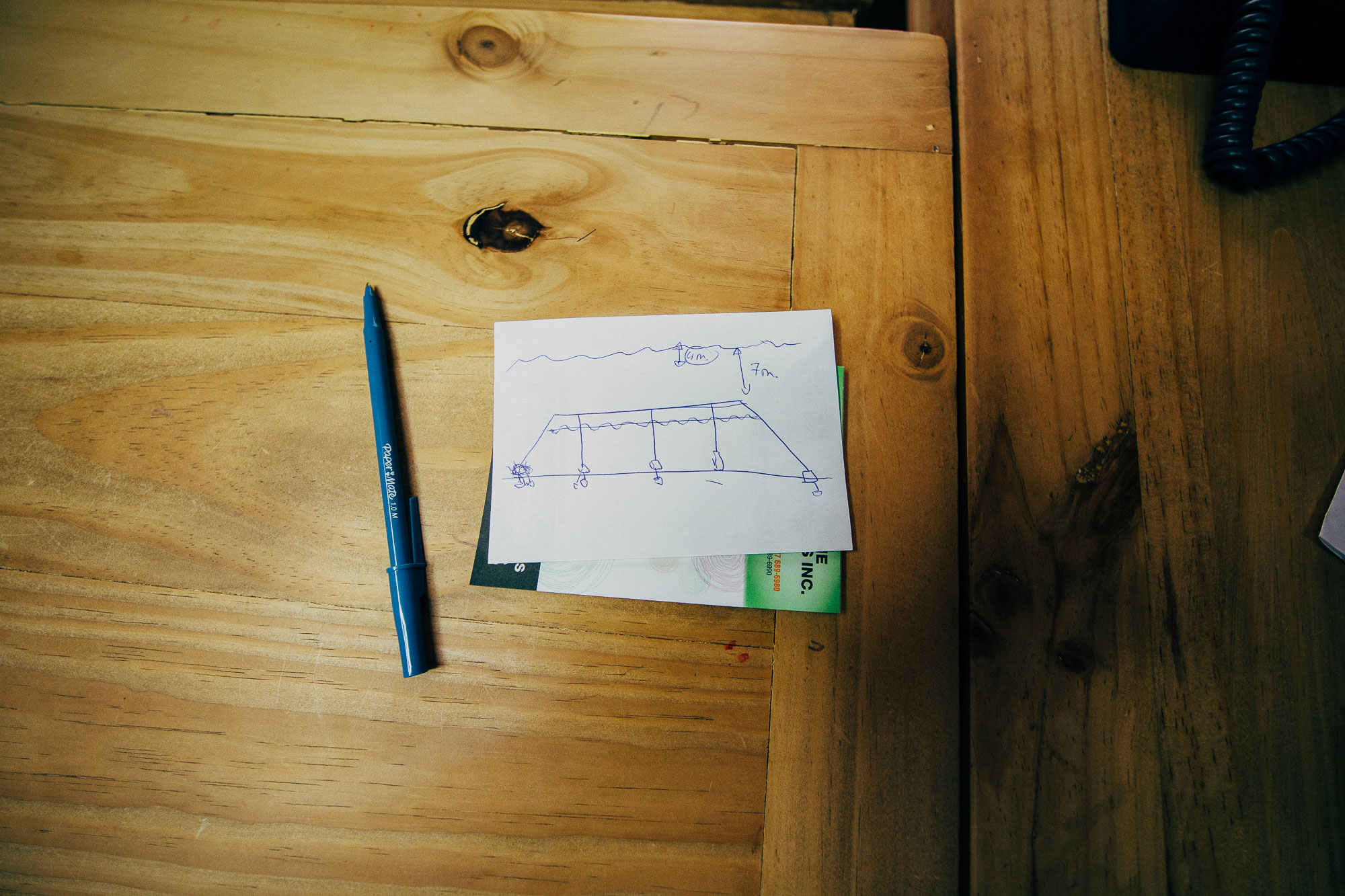

The process itself is fascinating and I’m sure I didn’t catch all the details. Essentially, they use a base that has a long rope with kelp seedlings attached to it. It gets lowered to a depth of seven metres in October, then raised to four metres in the springtime in order to benefit from the light and nutrients closer to the surface. In my mind, the process is comparable to growing lettuce. They harvest it for the blades, like leaves of lettuce, and process it before it reproduces.

I suppose this isn’t surprising but it seemed exciting to me that scientific research has discovered a number of benefits to ocean health provided by kelp forests. Sandra knew all about them. “The cultivation of kelp is environmentally beneficial in many ways,” she said. “They’re like filters, like organic captors that act to slow ocean acifidication, which is a major problem.” She talked about research being done in New Brunswick. They’re researching metatrophic aquaculture, using mussels and kelp to discover how kelp cleans the water from organic carbon emitted by other organisms in the water. “So there’s many things that benefit the ecosystem.”

Sandra also talked about the relations of Salaweg with the Indigenous communities in Gespe’gewa’gi. I felt like that was worth mentioning, since she herself is from France. She said she hopes that as the project grows it continues to gain Indigenous leadership.

I might be naïve but I think it’s really cool to have a product that is healthy, locally made, and beneficial for the environment in which it was grown. I guess I don’t know so much about the effects of agriculture and forestry on the ecosystems that they impact, but it seems to me that the kelp forest is unique in how significantly it benefits its surroundings. Not to mention offering local employment and supporting the sustainable management and conservation of ocean ecosystems.

As Sandra said in an interview with Radio-Canada, “On a tous le sentiment que c’est le début d’une grande histoire.”

“We all have the feeling that this is the beginning of a great story.”