A few weeks ago we stayed with Michel and Lucille on the northwest coast of Cape Breton. One of the things I had heard about while we were on Newfoundland was the history and continued practice of forced relocation of isolated communites. Lucille had a direct connection to that history; her father had been forced to move south to Chéticamp when the federal government established Cape Breton Highlands National Park in the 1930s.

So it was after my conversations with Lucille that I looked up more about the history of relocation in Atlantic Canada, and that’s when I came across a document from the National Library of Canada, Engineered Consent: The Relocation of Black Point by Lorraine Vitale Cox. The entire PDF is almost 500 pages, so I haven’t and most likely won’t read through it closely. But I saved it on my phone and took some time to scroll through it, reading different pieces of the culture and history of Black Point.

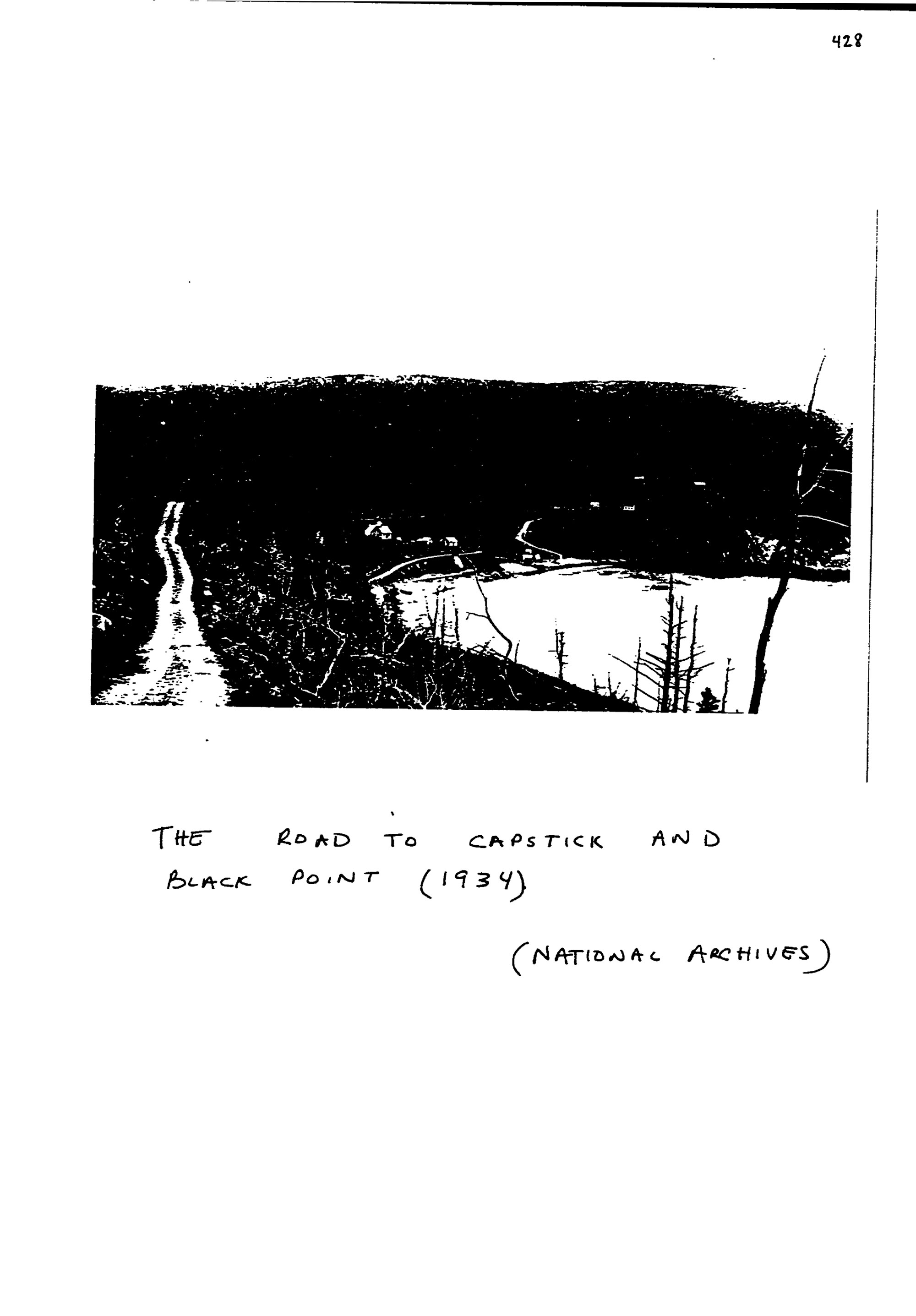

Black Point is found on the northwestern tip of the Bay of St. Lawrence in the highlands of Cape Breton Island. It’s isolated and always has been. Today, it’s abandoned. In its peak, however, it was a small Gaelic fishing community with a strong culture and connection to the ocean.

I’m going to pull a few quotes from the document that I found to be particularly important.

“Our ‘remembrance of things past’ as as much to do with our present experience as it does with our past. We forget much more than we remember. The process is one of sifting and winnowing out the chosen kernels of memory from the rest—the weightless chaff that simply disappears as our stories are told. This process, though, is not entirely of our own making. There are many things we are taught to remember and many we are taught to forget. These shape our experience not only of what was in the past but also of the present and the future.”

“This is the story,” begins Cox, “of the relocation of a small fishing community in Northern Cape Breton called Black Point.”

“By the end of 1971, the community of Black Point was empty. The houses there had all been torn down by government order, as part of a relocation agreement that was signed by community members. The people had been living in them were moved either to Bay St. Lawrence about four miles southeast or to Baddeck, the county seat, about 100 miles south. Until 1971, the population of Black Point was recorded in Local Subdivisions volume of the Canadian Census. Five years later, there was just a blank line where the population figure should have been. Officially, the community had ceased to exist.”

“The community may have no physical existence anymore but Black Point is still very much alive in the minds and hearts of the people who had lived there.”

“There are many stories to tell about Black Point, stories that need to be told. What troubles me, though, is that the ‘official’ version of the relocation of this small community is the only one being told and it is considered to be objective and true.”

“This does not mean that I can tell the community’s side to the story,” she adds. “That would be presumptuous on my part. I do hope, however, that my research will make it easier for the people in Black Point to remember so that they can begin to find their own voices and tell their own stories.”

You can see why this document caught my interest.

Cox goes into really quite exceptional detail about the culture of Black Point, beginning with the property rights of Scottish clansmen long before the arrival of their descendents on the north coast of Cape Breton. She talks about European migration, resistance to English language schooling, subsistence living, infrastructure developments, welfare and governmental interventions. Off the top of my head.

She describes, for example, a ritual of hospitality that involved the host offering tea, the guest refusing it, and the host making it anyway. “Usually, the host will remark that there is no need to take off the boots or shoes; but the visitor will take them off anyway. The guests walk directly into the doorway but not into the house. They stand by the door until they are invited in and asked to sit down. Guests rarely take their coats off and will often sit for hours with them on no matter how warm the kitchen is. Visitors are encouraged, however, to take their coats off through the entire visit. The proper response is to say that it is time to go.”

It hardly sounds like a group of uneducated Gaelic squatters who are eking out a miserable existence on unlawful land. If anything, it sounds like a rich culture in which poverty isn’t part of an equation of generosity and interdependence.

“There was a sense of plenty and abundance that accompanied tea. There was plenty of tea, plenty of time, and certainly plenty of scones. The whole encounter seemed to be completely spontaneous and there was never a sense of any kind of obligation to the patterns that everyone expected.”

“In the end the relocation in Black Point really had more to do with the interests of the state and the business ethos that it supported than it did with the needs of the people in the communities.”

Cox quotes a CBC documentary from 1986: “It suited all three levels of government to move those people out of there. The provincial government was worried about providing educational and highway services. The County of Victoria was worried about the size of the welfare bill, and the federal government had a long range view of expropriating that whole area into the national park. All of a sudden all three levels of government wanted those people out of there and they moved them for reasons that were not entirely related to the needs of the people.”

The people who lived in Black Point weren’t, in the end, given a choice. They were considered “backward” and uneducated, according to the Department of Public Welfare. “The relocation was designed to free them from traditional patterns of culture that were perceived to be holding them back. To force them to be free.”

Forced relocation isn’t something I know a lot about. I know from the perspective of administrative logistics, it’s perhaps technically justifiable. But it’s also a loss. The Black Point community had a powerful sense of self, connections to each other that were carried through multiple generations of Gaelic tradition and shared experience. I read about days of berry picking, shared beds on cold winter nights, a capella folk songs; and through it all families that had known each other for generations.

When Black Point was relocated, all of that was erased. Even with the entry of the road and that kind of ‘progress,’ the families lost some of what they once had. When they moved to Bay of St. Lawrence, Sydney and Baddeck, they lost each other.

“There are really many ways to cultivate the ground of community,” concludes Cox. “But a community culture can never survive if the individuals in it are exploited and compelled by the people outside of it.”

“I do not think we should try to live in the past but I do not think that we can escape it or run from it. […] We need to find our hearts again.”

Photos from the Nova Scotia Archives and National Library of Canada.