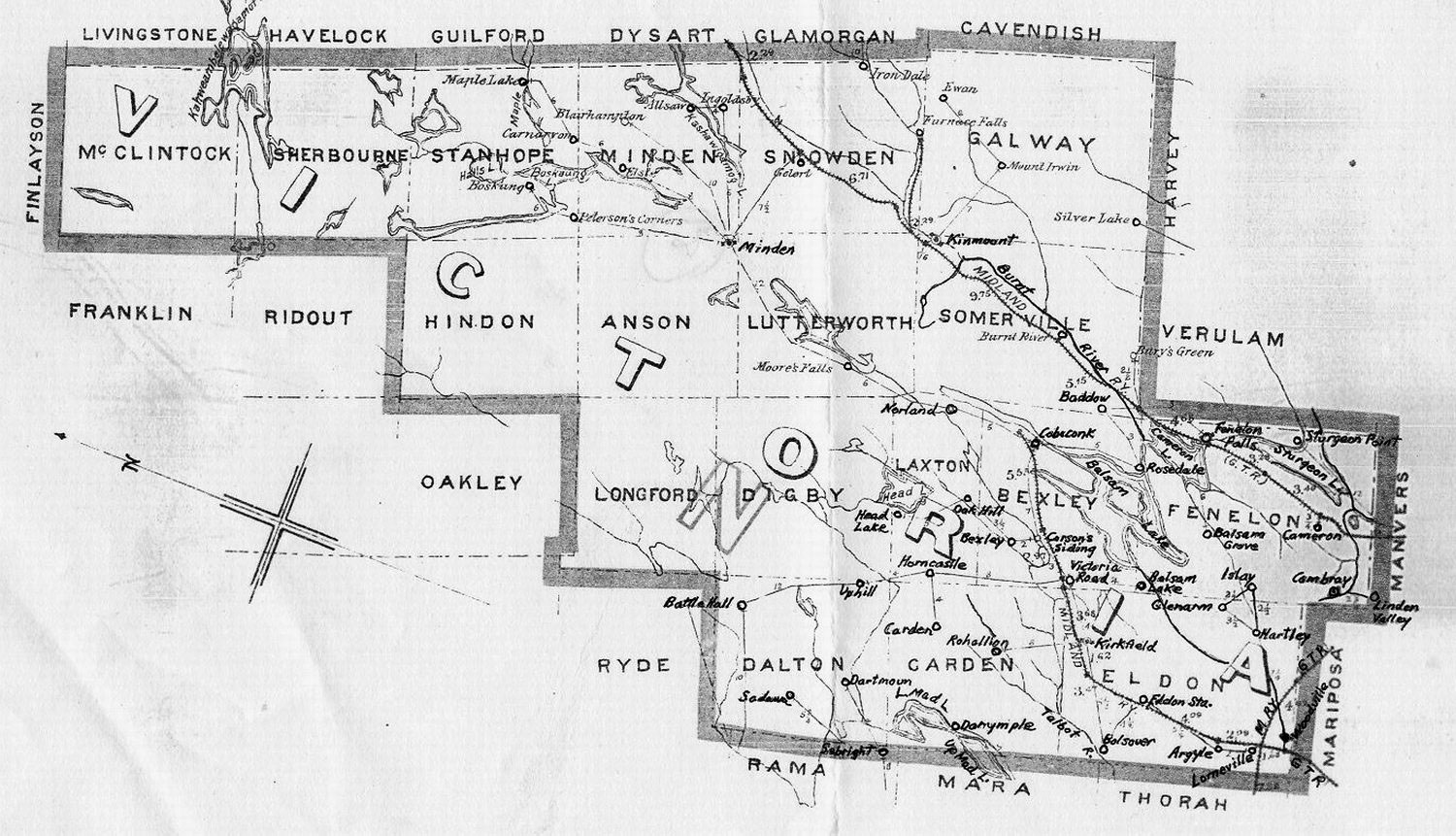

I grew up on an isolated property north of County Road 45, which was Digby Township in my young life and has now amalgamated into the City of Kawartha Lakes. My home was among young pines and old maples, fields of juniper and hawthorn. My siblings and I explored the swamps, the forests, the granite bedrock. We had stories for the dying oaks and the gloomy cedars and every place had a name.

I thought I knew my home.

And in the context of my short life at 9 or 10 years old, perhaps I did. But even then the land had seen centuries I never imagined, and I’m not ashamed to admit that I didn’t have any idea of its history, nor did I even suspect that there was a history worth knowing. That changed in the last few years, with two major learning experiences that transformed my sense of place and brought ongoing issues of stewardship, sustainability and Indigenous rights right against my heart.

A Land of Treaties

As a kid and a young teenager, I knew my property had been abandoned by its previous owners in the 1960s, and that was it. It never occurred to me to wonder who or what had preceded that.

Colonialism at its finest.

Then, as part of a university First Nations history course, I was tasked with researching my local area’s treaty history, and was taken aback to find that my family’s property lay on land ‘surrendered’ in 1818 as part of the Rice Lake Treaty. This treaty was at best a symbolic tool of systematic European expansion, and at worst an intentional, unilateral exploitation of a struggling people. The Mississauga chiefs were promised a perpetual annuity, continued land rights and a relationship of kinship and respect.

I never knew they existed.

“Our ancestors acquiesced cheerfully in the belief that they could hunt where and when they wished—‘as long as the grass grows and the water runs’—so ran the agreement signed by Indian chiefs and representatives of His Majesty’s Government. This was the law and promise which our ancestors deemed invulnerable as the laws of the Medes and Persians, but which later proved to be only a scrap of paper.” Mary Jane Muskratte Simpson, A History of the Rice Lake Indians

As I learned this, I figured it wasn’t completely applicable to the specific place I called home. It just wasn’t good land. How many Indigenous people could really have made a living on that barren granite and shallow rock-filled soil? At the most it would have been a waypoint between more desirable destinations.

I wasn’t wrong in thinking our land was undesirable. I was, however, wrong in thinking it had always been that way.

A Land of Fire

“The land itself,” writes Vernon LeCraw, “was covered by virgin forest, the growth of ventures in which only the biggest and best of the trees had survived. This is especially true where the great white pine held sway—and they were most numerous of all, particularly in Digby. The park-like forests teemed with wildlife.” He goes on to describe wild pigeons darkening the sun, the waters swarming with fish, beaver, otter, ducks and geese; and the forest holding game in quantities akin to paradise.

LeCraw notes the remnants of a five-mile deer fence, designed and laborously constructed to hunt deer effectively, presumably by the dozen Indigenous villages and camps nearby. This clearly wasn’t a bleak waypoint, as I had thought. This was a land of abundance, held in balance by the long-term stewardship of its inhabitants.

It didn’t last. The ruins of their villages lingered, but are now lost to the wild.

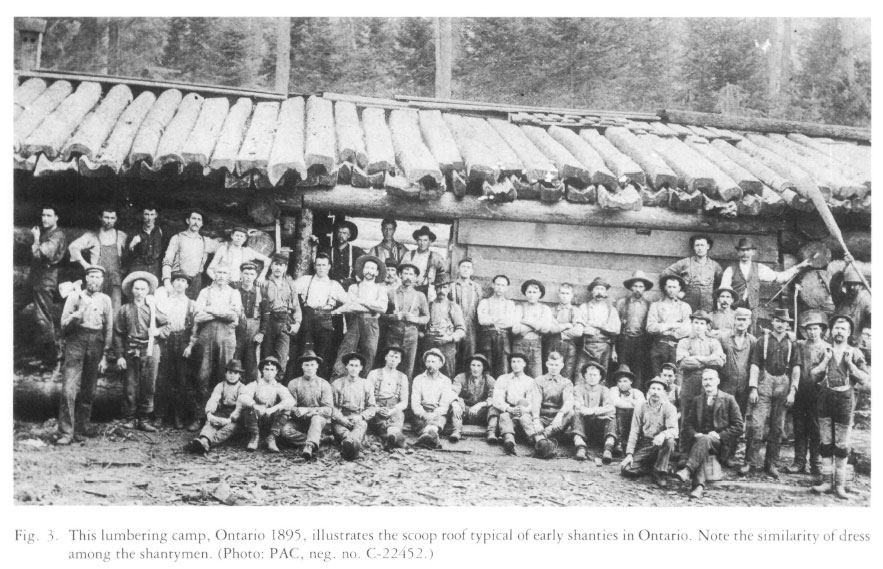

By the mid-19th century, huge demand for timber in the United States and Britain brought the lumber industry along the rivers and lakes of interior Ontario to the Northern Townships. Settlement, infrastructure and devastation followed.

“The story of Longford Township is one of tall pine timber, crashing logs on flooding waters, sturdy lumberjacks and raging forest fires. It is the story of the South Ontario lumber industry itself.”Frances Laver, Longford Township Made a Lumber Empire

I don’t know the details of the saga of the Longford Lumber Company, but I know that it pillaged this area with an annual output of twenty-eight million feet of pine in two mills alone, supplying the US and Britain with the lifeblood of empire. As local historian Watson Kirkconnell writes, “The lumberman’s axe echoed through the forests from the Kawartha Lakes north to Laxton and Longford and far beyond.” By the first decades of the 20th century, the magnificent forests were exhausted, their remains ravaged by forest fires and the country “left in its naked sterility of scarred rock.”

That is the legacy of my ancestors in this place: industry and fire and a capitalist venture that never once looked back.

Knowing what I know now, I treasure the land-based stories of my youthful adventures and imagination, and I also carry the painful, defining history that precedes them. I am not here by happenstance. I am intrinsically part of a long history on this land that has witnessed both hope and heartbreak. This doesn’t mean that I feel guilty for my lineage, but it does mean I have a responsibility to know my past and to decide what kind of future I believe in.

You have the same responsibility. Just like I did, it’s time for you to start asking questions about your home. How did you come to live where you do? What physical and historical foundations is your house built on? What stories lie just under your feet?

Asking these questions is a risk, because some answers are hard. I know that firsthand. If we take a lesson from the trees, however, hard ground means strong roots, and strong roots weather storms. I know that firsthand as well. Learning about my local history has given me a more powerful sense of place, and a more purposeful commitment to justice. My home is my home, but my past is not my future.

What’s yours?